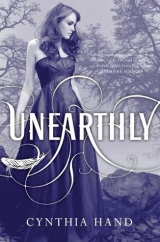

Текст книги "Unearthly"

Автор книги: Cynthia Hand

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

Unearthly

Cynthia Hand

For John

The Nephilim were on the earth in those days—

and also afterward—when the angels went

to the daughters of men and had children by them.

They were the heroes of old, men of renown.

—Genesis 6:4

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1 – On Purpose

Chapter 2 – Yonder Is Jackson Hole

Chapter 3 – I Survived the Black Plague

Chapter 4 – Wingspan

Chapter 5 – Hot Bozo

Chapter 6 – A-Skiing I Will Go

Chapter 7 – Flock Together

Chapter 8 – Blue Square Girl

Chapter 9 – Long Live the Queen

Chapter 10 – Flying Lesson

Chapter 11 – Idaho Falls

Chapter 12 – Shut Up and Dance

Chapter 13 – Goth Tinker Bell

Chapter 14 – The Jumping Tree

Chapter 15 – Tucker Me Out

Chapter 16 – Bear Repellent

Chapter 17 – Just Call Me Angel

Chapter 18 – My Purpose-Driven Life

Chapter 19 – Corduroy Jacket

Chapter 20 – Hurt Like Hell

Chapter 21 – Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

Chapter 22 – Down Came the Rain

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for Unearthly

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

In the beginning, there’s a boy standing in the trees. He’s around my age, in that space between child and man, maybe all of seventeen years old. I’m not sure how I know this. I can only see the back of his head, his dark hair curling damply against his neck. I feel the dry heat of the sun, so intense, drawing the life from everything. There’s a strange orange light filling the eastern sky. There’s the heavy smell of smoke. For a moment I’m filled with such a smothering grief that it’s hard to breathe. I don’t know why. I take a step toward the boy, open my mouth to call his name, only I don’t know it. The ground crunches under my feet. He hears me. He starts to turn. One more second and I will see his face.

That’s when the vision leaves me. I blink, and it’s gone.

Chapter 1

On Purpose

The first time, November 6 to be exact, I wake up at two a.m. with a tingling in my head like tiny fireflies dancing behind my eyes. I smell smoke. I get up and wander from room to room to make sure no part of the house is on fire. Everything’s fine, everybody sleeping, tranquil. It’s more of a campfire smoke, anyway, sharp and woodsy. I chalk it up to the usual weirdness that is my life. I try, but can’t get back to sleep. So I go downstairs. And I’m drinking a glass of water at the kitchen sink, when, with no other warning, I’m in the middle of the burning forest. It’s not like a dream. It’s like I’m physically there. I don’t stay long, maybe all of thirty seconds, and then I’m back in the kitchen, standing in a puddle of water because the glass has fallen from my hand.

Right away I run to wake Mom. I sit at the foot of her bed and try not to hyperventilate as I go over every detail of the vision I can remember. It’s so little, really, just the fire, the boy.

“Too much at once would be overwhelming,” she says. “That’s why it will come to you this way, in pieces.”

“Is that how it was when you received your purpose?”

“That’s how it is for most of us,” she says, neatly dodging my question.

She won’t tell me about her purpose. It’s one of those off-limits topics. This bugs me because we’re close, we’ve always been close, but there’s this big part of her that she refuses to share.

“Tell me about the trees in your vision,” she says. “What did they look like?”

“Pine, I think. Needles, not leaves.”

She nods thoughtfully, like this is an important clue. But me, I’m not thinking about the trees. I’m thinking about the boy.

“I wish I could have seen his face.”

“You will.”

“I wonder if I’m supposed to protect him.”

I like the idea of being his rescuer. All angel-bloods have purposes of different types—some are messengers, some witnesses, some meant to comfort, some just doing things that cause other things to happen—but guardian has a nice ring to it. It feels particularly angelic.

“I can’t believe you’re old enough to have your purpose,” Mom says with a sigh. “Makes me feel old.”

“You are old.”

She can’t argue with that, being that she’s over a hundred and all, even though she doesn’t look a day over forty. I, on the other hand, feel exactly like what I am: a clueless (if not exactly ordinary) sixteen-year-old who still has school in the morning. At the moment I don’t feel like there’s any angel blood in me. I look at my beautiful, vibrant mother, and I know that whatever her purpose was, she must have faced it with courage and humor and skill.

“Do you think . . . ,” I say after a minute, and it’s tough to get the question out because I don’t want her to think I’m a total coward. “Do you think it’s possible for me to be killed by fire?”

“Clara.”

“Seriously.”

“Why would you say that?”

“It’s just that when I was standing there behind him, I felt so sad. I don’t know why.”

Mom’s arms come around me, pull me close so I can hear the strong, steady beating of her heart.

“Maybe the reason I’m so sad is that I’m going to die,” I whisper.

Her arms tighten.

“It’s rare,” she says quietly.

“But it does happen.”

“We’ll figure it out together.” She hugs me closer and smoothes the hair away from my face the way she used to when I had nightmares as a kid. “Right now you should rest.”

I’ve never felt more awake in my life, but I stretch out on her bed and let her pull the covers over us. She puts her arm around me. She’s warm, radiating heat like she’s been standing in sunshine, even in the middle of the night. I inhale her smell: rosewater and vanilla, an old lady’s perfume. It always makes me feel safe.

When I close my eyes, I can still see the boy. Standing there waiting. For me. Which seems more important than the sadness or the possibility of dying some gruesome fiery death. He’s waiting for me.

I wake to the sound of rain and a soft gray light seeping through the blinds. I find Mom standing at the kitchen stove scraping scrambled eggs into a serving bowl, already dressed and ready for work like any other day, her long, auburn hair still wet from the shower. She’s humming to herself. She seems happy.

“Morning,” I announce.

She turns, puts down the spatula, and crosses the linoleum to give me a quick hug. Her smile is proud, like that time I won the district spelling bee in third grade: proud, but like she never expected anything less.

“How are you doing this morning? Hanging in there?”

“Yeah, I’m fine.”

“What’s going on?” my brother, Jeffrey, says from the doorway.

We turn to look at him. He’s leaning against the doorjamb, still rumpled with sleep and smelly and grumpy as usual. He’s never been what you might call a morning person. He stares at us. A flicker of fear crosses his face, like he’s bracing for horrible news, like someone we know has died.

“Your sister has received her purpose.” Mom smiles again, but it’s less jubilant than before. A cautious smile.

He looks me up and down like he’ll be able to find evidence of the divine somewhere on my body. “You had a vision?”

“Yeah. About a forest fire.” I shut my eyes and see it all again: the hillside crowded with pine trees, the orange sky, the smoke rolling past. “And a boy.”

“How do you know it wasn’t just a dream?”

“Because I wasn’t asleep.”

“So what does it mean?” he asks. All this angel-related information is new to him. He’s still in that time when the supernatural stuff can be exciting and cool. I envy him that.

“I don’t know,” I tell him. “That’s what I’ve got to find out.”

I have the vision again two days later. I’m in the middle of jogging laps around the outside edge of the Mountain View High School gymnasium, and suddenly it hits me, just like that. The world as I know it—California, Mountain View, the gym—promptly vanishes. I’m in the forest. I can actually taste the fire. This time I see the flames cresting the ridge.

And then I almost crash into a cheerleader.

“Watch it, dorkina!” she says.

I stagger to one side to let her pass. Breathing hard, I lean against the folded-up bleachers and try to get the vision back. But it’s like trying to return to a dream after you’re fully awake. It’s gone.

Crap. No one’s ever called me a dorkina before. Derivative of dork. Not good.

“No stopping,” calls Mrs. Schwartz, the PE teacher. “We want to get an accurate record of how fast you can run a mile. That means you, Clara.”

She must have been a drill sergeant in another life.

“If you don’t make it in less than ten minutes you’ll have to run it again next week,” she hollers.

I start running. I try to focus on the task at hand as I swoop around the next corner, keeping my pace quick to make up some of the time I’ve lost. But my mind wanders back to the vision. The shapes of the trees. The forest floor under my feet strewn with rocks and pine needles. The boy standing there with his back to me as he watches the fire approach. My suddenly so-very-rapidly-beating heart.

“Last lap, Clara,” says Mrs. Schwartz.

I speed up.

Why is he there? I wonder, not closing my eyes but still seeing his image like it’s burned onto my retinas. Will he be surprised to see me? My mind races with questions, but underneath them all there is only one:

Who is he?

At that point I blow past Mrs. Schwartz, sprinting hard.

“Good, Clara!” she calls. And then, a minute later, “That can’t be right.”

Slowing to a walk, I circle back to find out my time.

“Did I get it under ten minutes?”

“I clocked you at five forty-eight.” She sounds truly shocked. She looks at me like she’s having visions too, of me on the track team.

Whoops. I wasn’t paying attention, wasn’t holding back. I’m going to catch some major flack if Mom finds out.

I shrug.

“The watch must have been messed up,” I explain, trying for laid-back, hoping she’ll buy it even though it means I’ll have to run the stupid thing again next week.

“Yes,” she says, nodding distractedly. “I must have started it wrong.”

That night when Mom gets home she finds me slouched on the couch watching reruns of I Love Lucy.

“That bad, huh?”

“It’s my fallback when I can’t find Touched by an Angel,” I reply sarcastically.

She pulls a pint of Ben and Jerry’s Chubby Hubby out of a paper sack. Like she read my mind.

“You’re a goddess,” I say.

“Not quite.”

She holds up a book: Trees of North America, A Guide to Field Identification.

“Maybe my tree’s not in North America.”

“Let’s just start with this.”

We take the book to the kitchen table and bend over it together, searching for the exact type of pine tree from my vision. To someone on the outside we’d look like nothing more than a mother helping her daughter with her homework, not a pair of part-angels researching a mission from heaven.

“That’s it,” I say at last, pointing to a picture in the book and then rocking back in my chair, feeling pretty pleased with myself. “The lodgepole pine.”

“Twisted yellowish needles found in pairs,” Mom reads from the book. “Brown, egg-shaped cone?”

“I didn’t get a close look at the pinecones, Mom. It’s just the right shape, with the branches starting partway up the trunk like that, and it feels right,” I answer around a spoonful of ice cream.

“Okay.” She consults the book again. “It looks like the lodgepole pine is found exclusively in the Rocky Mountains and the northwestern coast of the U.S. and Canada. The Native Americans liked to use the trunks for the main supports in their wigwams. Hence the name lodgepole. And,” she continues, “it says here that the cones require extreme heat—like, say, from a forest fire—to open and release their seeds.”

“This is so educational,” I quip. Still, the idea of a tree that only grows in burned places sends a quiver of excitement through me. Even the tree has a kind of predestined meaning.

“Good. So we know roughly where this will happen,” says Mom. “Now all we have to do is narrow it down.”

“And then what?” I examine the picture of the pine tree, suddenly imagining the branches in flames.

“Then we’ll move.”

“Move? As in leave California?”

“Yes,” she says. Apparently she’s serious.

“But—” I sputter. “What about school? What about my friends? What about your job?”

“You’ll go to a new school, I imagine, and make new friends. I’ll get a new job, or find a way to do my job from home.”

“What about Jeffrey?”

She gives a little laugh and pats my hand like it’s a silly question. “Jeffrey will come, too.”

“Oh yeah, he’ll love that,” I say, thinking about Jeffrey with his army of friends and his never-ending parade of baseball games, wrestling matches, football practices, and everything else. We have lives, Jeffrey and I. For the first time it occurs to me that I’m in for so much more than I’ve anticipated. My purpose is going to change everything.

Mom closes the book about trees and meets my eyes solemnly across the kitchen table.

“This is the big stuff, Clara,” she says. “This vision, this purpose—it’s why you’re here.”

“I know. I just didn’t think we’d have to move.”

I look out the window into the yard I’ve grown up playing in, my old swing set that Mom has never gotten around to taking down, the row of rosebushes against the back fence that have been there for as long as I can remember. Behind the fence I can barely make out the hazy outline of the distant mountains that have always been the edges of my world. I can hear the Caltrain rumble as it crosses Shoreline Boulevard, and, if I concentrate hard enough, the faint music from Great America two miles away. It seems impossible that we would ever leave this place.

A corner of Mom’s mouth quirks up into a sympathetic smile.

“You thought you could just fly in somewhere for the weekend, complete your purpose, and fly back?”

“Yeah, maybe.” I glance away sheepishly. “When are you going to tell Jeffrey?”

“I think that should wait until we know where we’re going.”

“Can I be there when you tell him? I’ll bring popcorn.”

“Jeffrey’s turn will come,” she says, a muted sadness coming up in her eyes, that look she gets when she thinks we’re growing up too fast. “When he receives his purpose you’ll have to deal with that too.”

“And then we’ll move again?”

“We’ll go where his purpose leads us.”

“That’s crazy,” I say, shaking my head. “This all seems crazy. You know that, right?”

“Mysterious ways, Clara.” She grabs my spoon and digs a big chunk of Chubby Hubby out of the carton. She grins, shifting back into mischievous, playful Mom right before my eyes. “Mysterious ways.”

Over the next couple weeks the vision repeats every two or three days. I’ll be minding my own business and then bang—I’m in a service announcement for Smokey the Bear. I come to expect it at odd times, on the ride to school, in the shower, eating lunch. Other times I get the sensation without the vision itself. I feel the heat. I smell smoke.

My friends notice. They stick me with an unfortunate new nickname: Cadet, as in Space Cadet. I guess it could be worse. And my teachers notice. But I get the work done, so they don’t give me too much grief when I spend the class period scribbling away in my journal on what can’t possibly be class notes.

If you looked at my journal a few years ago, that fuzzy pink diary I had when I was twelve with Hello Kitty on the cover, locked with a flimsy gold key I kept on a chain around my neck to keep it safe from Jeffrey’s prying eyes, you’d see the ramblings of a perfectly normal girl. There are doodles of flowers and princesses, entries about school and the weather, movies I liked, music I danced around to, my dreams of playing the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker, or how Jeremy Morris sent one of his friends to ask me to be his girlfriend and of course I said no because why would I want to go out with someone too cowardly to ask me out himself?

Then comes the angel diary, which I started when I was fourteen. This one’s a midnight blue spiral-bound notebook with a picture of an angel on it, a serene, feminine angel who looks eerily like Mom, with red hair and golden wings, standing on the sliver of the crescent moon surrounded by stars, beams of light radiating from her head. In it I jotted down everything Mom ever told me about angels and angel-bloods, every fact or piece of speculation I could coax out of her. I also recorded my experiments, like the time I cut my forearm with a knife just to see if I would bleed (which I did, a lot) and carefully noted how long it took to heal (about twenty-four hours, from when I made the cut to when the little pink line completely disappeared), the time I spoke Swahili to a man in the San Francisco airport (imagine the surprise for both of us), or how I could do twenty-five grands jetés back and forth across the floor of the ballet studio without getting winded. That was when my mom started seriously lecturing me about keeping it cool, at least in public. That’s when I started to find myself, not just Clara the girl, but Clara the angel-blood, Clara the supernatural.

Now my journal (simple, black, moleskin) focuses entirely on my purpose: sketches, notes, and the details of the vision, especially when they involve the mysterious boy. He constantly lingers at the edges of my mind—except for those disorienting moments when he moves blindingly to center stage.

I grow to know him through his shape in my mind’s eye. I know the sweep of his broad shoulders, his carefully disheveled hair, which is a dark, warm brown, long enough to cover his ears and brush against his collar in the back. He keeps his hands tucked into the pockets of his black jacket, which is kind of fuzzy, I notice, maybe fleece. His weight is always shifted slightly to one side, as if he’s getting ready to walk away. He looks lean, but strong. When he begins to turn I can see the faintest outline of his cheek, and it never fails to make my heart beat faster and my breath hitch in my throat.

What will he think of me? I wonder.

I want to be awe-inspiring. When I appear to him in the forest, when he finally turns and sees me standing there, I want to at least look the part of an angel. I want to be all glowy and floaty like my mom. I’m not bad looking, I know. Angel-bloods are a fairly attractive bunch. I have good skin and my lips are naturally rosy so I never wear anything but gloss. I have very nice knees, or so I’m told. But I’m too tall and too skinny, and not in the willowy supermodel sort of way but in a storklike, all-arms-and-legs sort of way. And my eyes, which come across as storm-cloud gray in some lights and gunmetal blue in others, seem a bit too big for my face.

My hair is my best feature, long and wavy, bright gold with a hint of red, trailing behind me wherever I go like an afterthought. The problem with my hair is that it’s also completely unruly. It tangles. It catches in things: zippers, car doors, food. Tying it back or braiding it never works. It’s like a living thing trying to break free. Within moments of wrestling it down, there are strands in my face, and within the span of an hour it usually slides out of its confines completely. It takes the word unmanageable to a whole new level.

So with my luck, I’ll never make it in time to save the boy in the forest because my hair will have snagged on a tree branch a mile back.

“Clara, your phone’s ringing!” Mom hollers from the kitchen. I jump, startled. My journal lays open on my desk in front of me. On the page is a careful sketch of the back of the boy’s head, his neck, his tousled hair, the hint of cheek and eyelashes. I don’t remember drawing it.

“Okay!” I yell back. I close the journal and slide it under my algebra textbook. Then I run downstairs. It smells like a bakery. Tomorrow’s Thanksgiving, and Mom’s been making pies. She’s wearing her fifties housewife apron (which she’s had since the fifties, although she wasn’t a housewife back then, she assures us) and it’s dusted with flour. She holds the phone out to me.

“It’s your dad.”

I raise an eyebrow at her in a silent question.

“I don’t know,” she says. She hands me the phone, then turns and discreetly exits the room.

“Hi, Dad,” I say into the phone.

“Hi.”

There’s a pause. Three words into our conversation and he’s already out of things to say.

“So what’s the occasion?”

For a moment he doesn’t say anything. I sigh. For years I used to practice this speech about how mad I was at him for leaving Mom. I was three years old when they split. I don’t remember them fighting. All I retained from the time they were together are a few brief flashes. A birthday party. An afternoon at a beach. Him standing at the sink shaving. And then there’s the brutal memory of the day he left, me standing with Mom in the driveway, her holding Jeffrey on her hip and crying brokenheartedly as he drove away. I can’t forgive him for that. I can’t forgive him for a lot of things. For moving clear across the country to get away from us. For not calling enough. For never knowing what to say when he does call. But most of all I can’t get past the way Mom’s face pinches up whenever she hears his name.

Mom won’t discuss what happened between them any more than she’ll dish about her purpose. But here’s what I do know: My mother is as close to being the perfect woman as this world is likely to see. She’s half angel, after all, even though my dad doesn’t know that. She’s beautiful. She’s smart and funny. She is magic. And he gave her up. He gave us all up.

And that, in my book, makes him a fool.

“I just wanted to know if you’re okay,” he says finally.

“Why wouldn’t I be okay?”

He coughs.

“I mean, it’s rough being a teenager, right? High school. Boys.”

Now this conversation has gone from unusual to downright strange.

“Right,” I say. “Yeah, it’s rough.”

“Your mom says your grades are good.”

“You talked to Mom?”

Another silence.

“How’s life in the Big Apple?” I ask, to steer the conversation away from myself.

“The usual. Bright lights. Big city. I saw Derek Jeter in Central Park yesterday. It’s a terrible life.”

He can be charming, too. I always want to be mad at him, to tell him that he shouldn’t bother trying to bond with me, but I can never keep it up. The last time I saw him was two years ago, the summer I turned fourteen. I’d been practicing my “I-hate-you” speech big-time in the airport, on the plane, out of the gate, in the terminal. And then I saw him waiting for me by the baggage claim, and I filled up with this bizarre happiness. I launched myself into his arms and told him I’d missed him.

“I was thinking,” he says now. “Maybe you and Jeffrey could come to New York for the holidays.”

I almost laugh at his timing.

“I’d like to,” I say, “but I kind of have something important going on right now.”

Like locating a forest fire. Which is my one reason for being on this Earth. Which I will never be able to explain to him in a thousand years.

He doesn’t say anything.

“Sorry,” I say, and I shock myself by actually meaning it. “I’ll let you know if things change.”

“Your mom also told me you passed Driver’s Ed.” He’s clearly trying to change the subject.

“Yes, I took the test and parallel parked and everything. I’m sixteen. I’m legal now. Only Mom won’t let me take the car.”

“Maybe it’s time we see about getting you a car of your own.”

My mouth drops open. He’s just full of surprises.

And then I smell smoke.

The fire must be farther away this time. I don’t see it. I don’t see the boy. A hot gust of gritty wind sends my hair flying out of its ponytail. I cough and turn away from the blast, swiping hair out of my face.

That’s when I see the silver truck. I’m standing a few steps away from where it’s parked on the edge of a dirt road. AVALANCHE, it says in silver letters on the back. It’s a huge truck with a short, covered bed. It’s the boy’s truck. Somehow I just know.

Look at the license plate, I tell myself. Focus on that.

The plate is a pretty one. It’s mostly blue: the sky, with clouds. The right side is dominated by a rocky, flat-topped mountain that looks vaguely familiar. On the left is the black silhouette of a cowboy astride a bucking horse, waving his hat in the air. I’ve seen it before, but I don’t automatically know it. I try to read the numbers on the plate. At first all I can make out is the large number stacked on the left side: 22. And then the four digits on the other side of the cowboy: 99CX.

I expect to feel crazy happy then, excited to have such an enormously helpful piece of information handed to me as easily as that. But I’m still in the vision, and the vision is moving on. I turn away from the truck and walk quickly into the trees. Smoke drifts across the forest floor. Somewhere close by I hear a crack, like a branch falling. Then I see the boy, exactly the same as he’s always been. His back turned. The fire suddenly licking the top of the ridge. The danger so obvious, so close.

The crushing sadness descends on me like a curtain dropping. My throat closes. I want to say his name. I step toward him.

“Clara? You okay?”

My dad’s voice. I float back to myself. I’m leaning against the refrigerator, staring out the kitchen window where a hummingbird hovers near my mom’s feeder, a blur of wings. It darts in, takes a sip, then flits away.

“Clara?”

He sounds alarmed. Still dazed, I lift the phone to my ear.

“Dad, I think I’m going to have to call you back.”