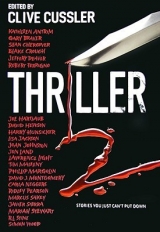

Текст книги "Thriller 2: Stories You Just Can't Put Down"

Автор книги: Clive Cussler

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

ROBERT FERRIGNO

Robert Ferrigno has a background that would give him instant credibility with the type of intelligent but questionable characters who populate his books. Armed with a degree in philosophy and a masters in creative writing, Robert left the academic trail to spend five years as a full-time gambler living in dangerous places with dangerous people. Then he became a journalist, but instead of sitting behind a desk typing, he landed a job that had him flying with the Blue Angels, test-driving Ferraris and learning about desert survival with gun enthusiasts. Now a bestselling thriller author, his experiences have clearly given Robert a unique perspective and an unforgettable voice.

“Can You Help Me Out Here?” showcases an ability to mix humor with suspense and a knack for creating villains that make us smile even as they send chills down our spine. No doubt Robert has met people like this somewhere in his travels. The rest of us will be happy to meet them through his words.

CAN YOU HELP ME OUT HERE?

“How much farther?” said Briggs.

The accountant tripped over a tree root, almost fell. Sweat rolled down his face, his hands duct-taped together behind his back. “Soon.”

Briggs grabbed the accountant by the hair and gave his head a shake. “How soon?” He jammed the barrel of the .357 Magnum against the man’s nasal septum. “You may like tramping around in the great outdoors, but me, I just want to shoot you and get into some air-conditioning.”

“I…I appreciate your discomfort,” said the accountant, blood trickling from his nose, “but Junior wants my ledger detailing his financial transactions for the last eight years, so…” He dripped blood onto his gray suit, a soft, pale man with calm eyes. “So you better treat me nice, and keep your part of the bargain.”

“Nice?” Briggs glowered at him, a beefy, middle-aged thug in a red tracksuit. “Maybe I fuck nice and just start blowing off body parts until you come up with it?”

“That would be a mistake on your part.” The accountant held his head high. “I have a…refined and delicate nature. I’m already experiencing heart palpitations from your rough treatment. You torture me…you could send me into shock. I might die before I give up the journal.” He sniffed back blood. “What do you think Junior will do to you then?”

“You didn’t tell me…” Briggs swatted at the mosquitoes hovering around him with the revolver. “You didn’t tell me we were going to be slogging through a swamp.”

“That’s where I hid it,” said the accountant. “And it’s not a swamp. It’s a wetlands.”

“Swamp, wetlands, who cares? It smells like an old outhouse,” said the other killer, Sean, a tall beach-bum with bad acne and a Save the Salmon, Eat More Pussy T-shirt. “What matters, mister, is that we’re going to keep our part of the bargain. You lead us to the journal, you get a double-tap to the back of the head, no muss, no fuss.”

“I abhor pain,” said the accountant.

“Trust me,” said Sean, “you won’t feel a thing.”

The accountant glanced at Briggs, then back at Sean. “Do I have your word on that?”

Sean gave him a thumbs-up. “Scout’s honor.”

“That’s not the goddamned Scout’s sign.” Briggs raised the index and middle finger of his right hand in a V. “This is Scout’s honor, dumb-ass.”

“That’s the peace sign,” said Sean, “and don’t call me dumb-ass.”

“It’s the peace sign and the sign for Scout’s honor,” said the accountant.

“What’s this then?” said Sean, giving the thumbs-up.

“Keep walking,” Briggs ordered the accountant, “and stay out of the poison ivy.”

The accountant started back down the narrow path, brush on all sides, trees overhanging the trail.

“Fine,” said Sean, hurrying to catch up to them, “don’t answer me.”

Five minutes later, the accountant turned to Briggs. “Are you saving your money?”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” said Briggs.

“A simple interrogatory,” said the accountant, his yellow necktie crusted with blood. “I wanted to know if you saved a portion of your money or lived paycheck to paycheck.”

Briggs swatted at the mosquitoes darting around him. “I do okay.”

“I could give you some suggestions,” said the accountant. “Something that would allow you to defer taxes and put your money to work for you—”

“Taxes?” Briggs laughed.

“You don’t pay taxes?” said the accountant.

Sean shook his head. “Me, neither.”

“Big mistake,” said the accountant. “You don’t want to fool with the IRS.”

“How much farther?” demanded Briggs.

“I kind of like the idea of my money working for me,” Sean said quietly. “Like having a maid. Or a slave.” He made a motion like he was cracking a whip.

“Good for you, Sean.” The accountant tried to scratch his nose with his shoulder. “Now you’re thinking. I can give you some tips—”

“You think this is a fucking seminar?” said Briggs. “Move!”

“Is that how you got this place?” Sean said to the accountant. “Making your money work for you?”

“Absolutely,” said the accountant. “I’ve got forty-five acres here, owned free and clear. Practically surrounded by national forest. I enjoy privacy…up until now.”

“We should listen to this guy before we pop him, Briggs,” said Sean. “Maybe take some notes.”

Briggs slapped a mosquito that had landed on his cheek, his face flushed and as red as the tracksuit now.

The accountant stopped.

“This it?” said Briggs. “Are we there?”

“Can you help me out here?” said the accountant. “I…I have to urinate.”

“You’re only going to have to hold it for a little while more,” said Briggs.

“I have been holding it,” said the accountant.

“What do you expect us to do about it?” said Briggs.

“I expect you to cut my hands loose,” said the accountant.

“I got nothing to cut the tape with and not sure I would if I could,” said Briggs. “We might not be able to find you if you take off running—this is your home turf.”

“I have no intention, Mr. Briggs, of wetting my pants,” said the accountant.

“If it puts your mind at ease, sir,” said Sean, “you’re going to piss yourself anyway when I give you the double-tap. It’s a natural reaction…loss of control, you know? A real mess, too. I seen it plenty times.”

“Yes, Sean, but I’ll be dead then, so it won’t matter to me,” said the accountant. “Now, being presently alive, it does matter.”

“Oh.” Sean nodded. “I get it.”

The accountant wiggled his fingers behind his back. “Do you mind?”

Sean bent over the accountant’s hands, tearing at the tape, while the accountant shifted from one foot to the other.

“Please hurry, Sean,” said the accountant.

“Tapes all tangled up,” said Sean. “I…I can’t do it.”

“Told you, dumb-ass,” said Briggs. “That’s why I use that kind of tape, ’cause you can’t get it off.”

“Then one of you is going to have to unzip my trousers and hold my penis while I urinate,” said the accountant.

Both Sean and Briggs burst out laughing.

“I’m quite serious, gentlemen,” said the accountant.

“Pal, if you want someone to hold your joint, you’re out of luck,” said Briggs, still laughing. “Now, I had a partner ten years ago…he might have accommodated you.”

“If you force me to wet myself, Mr. Briggs, I can promise you with absolute certainty, that I will not lead you to the ledger, no matter what you do to me,” said the accountant.

Briggs punched the accountant in the side of the head, knocked him onto the ground. “You sure about that?” He kicked the man in the chest, then grabbed the accountant’s bound hands, jerked him to his feet, bones popping. “You sure?”

The accountant didn’t say a word.

Briggs lifted the accountant’s hands higher and higher, the man bent forward, silent, tears rolling from his eyes onto the dirt. Still silent. Briggs finally released him, out of breath.

“Damn, Briggs,” said Sean. “I believe him.”

“Yeah,” panted Briggs. “So do I.” He wiped sweat off his forehead with the back of his hand. “So grab his joint and help him take a piss.”

“Me?” said Sean.

Briggs shrugged. “I cleaned up after the two software geeks. They must have had the combo platter at El Jaliscos but you never heard me complain. While you were ‘oohing’ and ‘aahing’ over their fancy laptops, I was mopping out the car.”

“I’m not doing it,” said Sean.

“You were the one who forgot the handcuffs,” said Briggs. “That’s why I had to use the tape.”

“I don’t care,” said Sean.”

“Gentlemen,” said the accountant. “Decide.”

“Did I share on the last job?” said Briggs. “I didn’t have to, but I did.” He glanced at the accountant. “Last job we found…I found a half-kilo of smack in Mr. Unlucky’s dresser. I didn’t have to share it with you, but I did.”

“The smack was stepped on, and we probably should have turned it over to Junior anyway,” said Sean.

“Gentlemen?”

Sean stared at Briggs.

“You know it’s fair,” said Briggs.

Sean jabbed a finger at the accountant. “I ain’t touching it with my bare hands.” He walked around until he found a tree with wide leaves, tore a couple off and strode back to the accountant. “Don’t say a fucking word.” He unzipped the accountant’s trousers, fumbled out the man’s penis holding the leaf around it, then pointed it into the brush. “Hurry up.”

The accountant closed his eyes.

“Come on,” said Sean, giving the accountant’s penis a slight shake.

“I’m trying,” said the accountant.

“You’re the one who had to go so bad,” said Sean.

“Oh, Sean,” drawled Briggs, “I cain’t quit you.”

“That ain’t funny.” Sean looked at the accountant. “I’m going to be hearing that for the next week.”

The accountant sighed. “I…I can’t do it. It’s just…I can’t.”

“Fine.” Sean stuffed the accountant’s penis back into his trousers, didn’t even bother zipping him up, the leaf sticking out of his fly. “Just take us to the damn ledger so I can blow your brains out and forget this ever happened.”

“I’m sorry,” said the accountant. “It’s not easy, you know.”

Sean wiped his hand on his pants.

“If it helps,” said the accountant, “we’re almost there.”

“About time.” Briggs looked down at the patches of standing water all around them. “Getting really muddy.”

“Lot of rain lately,” said the accountant, walking ahead, the ground sucking at his shoes. “It’s really beautiful here after a storm, all kinds of flowers popping up.” He walked slightly off the trail, splashed through a puddle. “See that tree up ahead?” He pointed with his chin. “The one with the split trunk? The journal’s in a waterproof container under a large flat rock—”

Briggs pushed him aside, stalked across a mossy clearing toward the tree, right through the water. He was in past his ankles trying to high-step free before he stopped and looked back. By then it was too late. He was up to his knees and sinking fast.

“Don’t move!” said the accountant.

“Get me out of here!” shouted Briggs.

Sean pointed a pistol at the accountant. “You did this.”

“There’s underground springs all over this part of the woods,” the accountant said to Sean, ignoring the pistol. “Nobody knows where they’ll pop up next.”

“Hey!” called Briggs, the muddy slurry almost to his waist now.

“Quit struggling, Briggs, you’ll only sink faster,” said the accountant, stepping slowly into the clearing. “Stay calm.”

“How about we trade places and you stay calm, mother-fucker?” said Briggs, perfectly still now.

“Sean, go find a long tree branch,” the accountant said gently. “Hurry.”

Sean crashed into the underbrush.

“I’m…I’m still sinking,” said Briggs, a cloud of mosquitoes floating around his head.

The accountant watched him stuck there, the late-afternoon light seeping through the trees.

Sean rushed back, dragging a long, dry branch. “Is this okay?”

“Perfect,” said the accountant. “Hold it out in front of you…but be careful where you step.”

“I’m scared,” said Sean.

“Fucking do it, Sean!” cried Briggs.

Sean edged carefully into the clearing, one foot in front of the other, testing the ground under the water to make sure it was solid. He waved the dry branch at Briggs.

“You’ll have to get closer,” said the accountant.

Sean took another few steps, started to sink, the watery muck level with his high-tops. He reached out with the branch.

Briggs lunged for the branch, missed it by at least three feet. His movements drove him deeper into the slurry, chest-high now. “Closer!”

“It’s okay, Sean,” said the accountant. “Just a little farther. Lean forward with the branch.”

Sean hesitated, took another step toward Briggs, bent over, the branch extended as far as he could.

The accountant put his foot against Sean’s ass, and pushed. Sent him sprawling.

Sean screamed, facedown, spitting out muck as he fought to get out, but only got sucked in deeper and deeper. He grasped at the tree branch. It snapped.

The accountant watched them struggle. Sean weeping, frantic, mud in his mouth, sinking fast. Briggs moved slowly, trying to work his way toward the edge of the clearing.

“There really is a natural spring under there,” said the accountant, hands still taped behind his back. “Been that way since I was a boy. Deep, too. No matter what you throw in, it just gets swallowed up. I tossed a neighbor’s new bicycle down there one time. Shiny red Schwinn with streamers on the handlebars and a chrome fenders. Never did like that kid.”

Briggs reached for a tuft of grass, but it came apart in his hands. He tilted back, the slurry past his chest now.

Sean made a final choking sound, and slipped under the surface.

“If you can hold your breath long enough, Briggs, maybe you can find that bike on the bottom,” said the accountant. “See if you can ring the bell.”

Briggs reached down, fumbled for something, the movement pushing him deeper. His head was under the surface when his hand broke free, just his hand, holding the .357. He blindly got off three shots with the revolver before his hand disappeared along with the rest of him.

One of the shots had been close enough that the accountant heard it zing past his ear, but he hadn’t flinched. Just smiled. You take your chances…

He stepped back from the quicksand, deftly slipped his bound hands under his feet and in front of him. He worked at the duct tape with his teeth. Took him ten minutes. The clearing was still by then.

The accountant rubbed his wrists, bringing back the circulation. He adjusted his necktie, then pulled out his cell and called Junior.

“It’s done,” said the accountant.

“It go down like you wanted?” said Junior.

A breeze stirred the grass around the edges of the quicksand. “Pretty much.”

“Nothing’s going to come back at us?”

“No.” The accountant watched a muddy bubble pop. “Not a thing.”

“I can’t abide thieves,” said Junior. “I need to be able to trust the people work for me.”

The accountant studied a couple of iridescent green dragon-flies hovering over the surface of the water.

“Never understood why you don’t just do things the easy way,” said Junior.

The accountant pulled the leaf Sean had used out of his fly, zipped up his pants.

“Where’s the fun in that?” He snapped the phone shut and started back toward his house.

JOE HARTLAUB

When he’s not practicing law, Joe Hartlaub is a highly respected book reviewer, so he’s no stranger to what makes a good thriller come to life. “Crossed Double” shows how sharp dialogue can make you feel like you’re not just reading a story but also eavesdropping on the two people at the table next to you in a restaurant.

The characters in “Crossed Double” might be made of questionable moral fiber but they are not without their own code of honor, as a father tries to explain to his wayward son. You could say that this story is a parent lecturing a child about right and wrong, but this is a thriller, so make that wrong and wrong.

CROSSED DOUBLE

C.T. is unhappy.

He shouldn’t be. He has time on his hands, money in the bank and pussy on the side. He has breakfast—coffee, cream, fried egg sandwich, cheese and sausage on a toasted bagel, crunchy but not dark, if you would be so kind—sitting in front of him at Lisa’s, his favorite diner in Columbus. His son, Andy, is sitting across from him, and it’s still like looking in a mirror, even though a quarter-century separates them. All should be well, except for the story that Andy is telling him. C.T. has to keep his hands on the table to keep from smacking the stupid out of the kid, which, C.T. thinks, would take about three weeks once he started. Eight years out of high school and still fucking up like a three-year-old.

Andy is telling C.T. that he borrowed money from Kozee, who is a whack-job. Everyone knows it. He’s a DLR—Doesn’t Look Right—and only a wet brain or someone fresh off of a Greyhound bus would ever do business with him. Even the girls who troll the Ohio State North Campus bars, with their tramp-stamps and thongs showing and who shave once a week whether they need to or not, find Kozee a little too outside of the box for what they have in mind.

Kozee fills a doorway wide and high, all muscle, bald head, cold blue eyes, veins running up and down his arms like one of those transparency pictures in a medical school textbook. He looks like he’s waiting to catch a ride from one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Any one will do. He gives off a primal odor of trouble, of danger, of death, a long and slow one devised especially for you. The Greenbrier Project boys, who cruise the Washington Beach grid with impunity and occasionally venture into the Glen Echo maze, step off when they see him shamble ’round the way. There are a hundred stories about Kozee, told in alleys that run behind no-name bars on East Fifth, on street corners in Hawaiian Point, in doorways of shabby apartments in those sections of the Short North where the gentrification begun twenty years ago hasn’t quite reached.

And Andy borrowed money from this guy, even after hearing how Kozee had gotten into the unsecured loan business. A Mex named Jeffe had been running the corner action on Fourth and Eleventh. Kozee had started hanging around and Jeffe, having missed the memo about Kozee, got into his face about it being bad for business, having a crazy-looking, fucked-up white boy hanging around, scaring business away. Kozee hadn’t said a word, just head-butted the silly beaner, breaking his nose, and then biting it off like it was a Tootsie Roll or something, spitting it back on him more or less in place. One of Jeffe’s crew tried to help him up, but Kozee said to stay away from him, just let him roll around screaming in the parking lot, let Jeffe figure out if that was good or bad for business. Kozee was back on the corner the next day, not saying it but everybody knew: it was his corner now. Wasn’t anyone there that was gonna argue with him, least of all Jeffe.

So nobody is fucking with Kozee. He is, as they say, shitting behind the tall cotton. Kozee is like a mutual fund; he’s involved in enough different enterprises so that if one dries up another usually picks up. Kozee took up a loan-sharking operation a few weeks ago when the mayor of Columbus, a high yellow with movie-star looks and the requisite ability to look competent without having a clue, declared a hapless war on drugs. So Kozee drops drugs and starts lending money at an interest rate that makes Chase Visa look like a benevolent enterprise. You don’t want to be late with Kozee. He doesn’t hire some bitch to call you every day and inquire about your payment. He breaks your door down and beats your ass. And this is the guy Andy goes to for a loan.

Andy’s thing with Kozee, however, is only part of the elephant pissing on C.T.’s morning. Andy’s stupidity isn’t limited to a business transaction with a psycho; no, Andy’s wires are crossed worse than that, as becomes evident when Andy starts talking about Rakkim.

C.T. knows Rakkim, a big guy, an underachiever in his midthirties who for seven years has been delivering pizza for Midnight Crisis, a twenty-four-hour North Campus pizza joint. Midnight Crisis has been described as “employing the unemployable since 1993,” and “unemployable” certainly applies to Rakkim, who up until a couple of months ago was a quiet guy who walked around oblivious, as if listening to an iPod through headphones or something, except that he doesn’t own an iPod. The only time that C.T. had seen him at all animated was in the Midnight Crisis party room at Rakkim’s thirtieth birthday party, which featured cake, liquor and a red-headed hooker from a High Street strip club, who gave Rakkim a lap dance and a blow job while those assembled, including the woman’s husband, howled in beery approval.

According to Andy, however, Rakkim has been acting like a little bitch for the last few months. Some third-string Ohio State tailback had given Rakkim shit about paying for a large pepperoni and slapped him across the face. Rakkim, totally out of character, had jacked the guy’s jaw, breaking it. All of a sudden, Rakkim becomes a legend in his own mind, acting out. Among other things—and this, according to Andy, is the cause of his instant problem—Rakkim hasn’t paid for a nickel bag that Jeff had fronted for him the month before.

C.T. remembers Jeff from when Andy was in high school, a quiet kid who wouldn’t say shit if he had a mouthful. According to Andy, Rakkim has no complaints with Jeff about the quality of the bag or shorting on the weight; Andy solemnly assures C.T. that Jeff would never do such a thing. Andy is pretending to be oblivious to the eye fuck that C.T. is giving him across the table at him. C.T. wondering, how do you know this? Now, Andy says, Rakkim just won’t pay Jeff, or return his phone calls, he’s just ignoring Jeff, blowing him off.

Jeff, according to Andy, is not a big-time dealer. Like a lot of the Washington Beach guys who deal small and local, he sells only to his friends with just enough markup for his own stash and to make his rent and lights. It’s a fragile street economics model that collapses if someone in the chain doesn’t come through. And Rakkim didn’t come through.

What has C.T. ready to play Whack-A-Mole with his son’s head in Lisa’s is that Andy has interjected himself into this mess. A couple of months ago Jeff, for whom budgeting is a science on the order of quantum physics, had been short for his rent. Andy, being a bro, and not wanting Jeff to interrupt his dealing, had slid a few Benjamins to Jeff. Now Jeff is telling Andy that since Rakkim had stiffed Jeff, Jeff had to stiff Andy. The result was that Andy was short, so…

“I went up to see Kozee,” Andy says. C.T. is looking at Andy across the dining table as if he was a turd floating in C.T.’s coffee. Lisa’s Café is quiet, only the two of them as customers, C.T. listening to this utter bullshit and torn between fatherly love and disgust. He begins mentally ticking off the various problems here—the borrowing of money, the drug involvement, the total fucking stupidity he is hearing come out of his son’s mouth—and shakes his head as he looks out of the front window.

Traffic on Indianola is quiet this early in the morning, and the sun is out, promising the first decent day after months of a bitterly cold and depressingly gray winter. C.T. had his breakfast sandwich cut into neat little squares and it’s now gone, though he cannot remember having eaten any of it. He is, as is his custom, dressed all in black, mock turtleneck and pants, shoes and socks, hat and leather coat. He sticks out at Lisa’s like a stiff prick at a county fair. He can tell that the owner of the restaurant, a gray-haired hippie who hasn’t changed his spectacles or his jeans since George McGovern ran for president, isn’t sure whether he likes C.T. and Andy coming here or not, their hood ambience not fitting in with the “peace, love and brotherhood” vibe of the place. They sit and mind their own business and never raise their voices, so fuck him, and besides, what is the guy going to say, don’t come here anymore, you’re scaring away my Nader For President traffic? For just a minute, C.T. wishes he was somewhere else, on a hotel balcony overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, lying on a chaise lounge and reading a novel while two twentysomethings in bikinis flip a coin to see who will give him warm head first.

C.T. shakes his head and looks at his son. “You remember Brando’s first line in The Godfather, Andy?” C.T. says, looking at him over the top of his coffee cup. Andy shakes his head, says no. C.T. widens his cheeks by grimacing, then does a more than passable Don Corleone, asking Andy, “Why didn’t you come to me first, instead of going to a stranger?”

Andy laughs, still amazed, at twenty-five, at his dad’s talent for mimicry. It’s an uncomfortable question, however, and C.T. is serious. Andy shakes his head again. “I wanted to get this one done on my own. I can’t keep coming to you all of the time.”

“I understand,” C.T. says. It takes an effort for him to keep his voice level. “But the last guy you want to have anything to do with is Kozee. You know how when you step in dogshit when you’re wearing cross-trainers, and it stays in the cracks forever, and you need a knife to dig it out but there’s always some left? That’s what dealing with Kozee is like.” He takes another sip of coffee. “But I don’t get why this was your problem. It was Jeff’s problem. And Jeff is now your problem. He borrowed the money from you. But he’s got money now, and you don’t. He still has money for dope, he hasn’t been evicted or anything, he’s not an orphan, and I saw him last night in the Surly Girl, trying to pick up what I think was a woman, who, regardless, was out of his league. So he’s got money. Your money.”

C.T. watches Andy sip on his soft drink—how can anyone drink that shit at 7:00 a.m., it’s beyond him—and waits for what’s next. Andy hasn’t changed since he was ten years old. When he gets caught in the juices of his own lies, he’ll slough deeper into the stew until he’s neck-high in his own bullshit.

Andy surprises him, though, coming at it from another direction. “How do you know?” he asks. Andy should know better, having heard enough stories about his dad—hell, he saw enough of them happening while he was growing up—that he’s aware that little happens on the north and east sides of town that his dad doesn’t know about. But he has to ask.

“How do you know?” he asks again.

C.T. ignores the question long enough to take a last sip of coffee, wondering how anyone—even an old hippie—outside of a police precinct house can fuck up a cup of Folgers. He motions for the check.

“How about,” he says, as he pulls a twenty out of his pocket to pay the bill, “I’ll show you.”

Jeff opens his eyes and he is looking up a big tube. The tube is hard metal, because when he starts to jump up he hits his forehead on it, and, considering all of the alcohol he drank the night before at the Surly Girl, his head doesn’t need any more aggravation. Aggravation is what he has, though. He’s got two guys in his bedroom, locked door notwithstanding, both of them wearing ski masks. Jeff starts to jump out of bed but his forward progress is impeded by the barrel of the gun that is now pressed up against his left eye. “Good morning, Starshine,” says the guy holding a gun, the guy nearest his bed, the guy wearing a gray ski mask and a blue peacoat. Jeff opens his mouth to scream but only a strangled little rasp comes out before the gun barrel is jammed between his teeth and down his throat. The guy with the gun says, “Wudda wudda” in a singsong voice and wags his finger from side to side, which for some reason scares Jeff more than the gun. “The only thing I want to hear out of you is information, my friend. Where are your Benjamins? No screams, no bullshit, no excuses, just where they are and we’ll be down the road.” Jeff feels the gun barrel ease out of his mouth so he can talk, but it’s still pointed at him, pressed directly against his forehead, hard. His eyes are crossing trying to look at it. He feels his bladder let loose under the covers, first it’s warm and then almost immediately cold, and he’s embarrassed, though the two guys don’t seem to notice. Jeff tries to scream, but his throat constricts and he can’t manage much more than a hysterical whisper. “The back of the closet! On the floor! There’s a suitcase full of dirty underwear! It’s in there!”

Gray keeps his eyes on Jeff but jerks his head at the other guy, the one wearing a black ski mask, and nods toward the closet. Black steps over to the walk-in and begins digging through the mess on the floor and finds the suitcase. He opens it up and hesitates for a second. He doesn’t want to stick his hand into the underwear, which is so filthy that it’s almost twitching, but he does anyway and after rooting through it for a couple of seconds he pulls out a thick wad of bills, folded over with a rubber band around it. He doesn’t say anything, just takes it over and holds it in front of Gray’s line of vision. Gray sticks his chin out and nods, and Black peels off ten bills, making sure that they’re not going to walk out of there with a Michigan roll.

Jeff is terrified. He looks like Linda Blair in The Exorcist, sweating and his eyes all wild. His head is pinned to the bed by the gun but his body is twitching uncontrollably. That money is promised to some nasty folks, and if it turns up missing Jeff will be better off being shot. The situation puts him next door to stupid, and that’s why, almost before he knows that he’s doing it, he grabs for the gun, trying to shove it away as he sits up, thinking that somehow the two guys will be distracted enough that he can get away. He hears a shout and then for just an instant the pain in his head gets a thousand times worse and then it all goes black.

“Fuck me,” C.T. says, leaning back in the driver’s seat of his car, Andy next to him. They’re parked out toward the street in a medical building parking lot off of Cleveland Avenue in Westerville, just a couple of guys who look like they’re waiting for a wife or a girlfriend getting an MRI or Pap smear or some fucking thing. Two ski masks—one gray, one black—are sitting on the console between them. “Fuck me. Who would have figured Jeff for Captain America?”

“Yeah, well Captain America died last year, and Jeff is still alive,” Andy says. “You think he’s awake yet?”

“I dunno. When he does wake up, he needs to go down to University Hospital and treat himself to a neurological.” C.T. shakes his head. “I smacked him pretty hard. Stupid asshole. Good thing the gun wasn’t loaded. They’d be finding little pieces of Jeff all over Washington Beach for the next year.” C.T. takes his pistol out of its pocket holster and begins reloading the 9-mm hollow points back into the clip, keeping an eye on the parking lot so as not to give anyone walking by a heart attack.