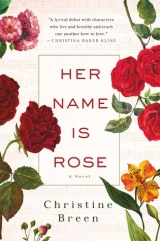

Текст книги "Her Name Is Rose: A Novel"

Автор книги: Christine Breen

Жанр:

Роман

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Two

Sunshine pouring through the window of her Camden Lock flat in North West London reminds Rose of the song about a Chelsea morning. The one with the milk and toast and the oranges and butterscotch. It reminds her of her mother singing when the spring sunlight returns to the kitchen in Ashwood—sometime in the middle of March—before the cuckoo comes, before the swallows return, and the tulips fade. For six months of the year no sun shines in the north-facing kitchen until that first ray of spring light squeezes in from the east. Her mad, loveable mother would start singing, nearly as good as Joni Mitchell.

Rose sings it now to herself as she stretches in the bed. She kicks off the duvet and slides to the edge, looking out her window on the canal below. Early-morning kayakers paddle. Seagulls squawk above the lock, noisy and loud. She loves the noise here compared to the utter quiet of the west of Ireland. She observes her room a moment before standing to dress, and counts, “One, two, three!” Three tea mugs. Not a record. She smiles, remembering the sort of Mexican stand-off she would sometimes have with her mother.

“So here’s where all the mugs have got to, Rosie!” her mother would say, stepping into Rose’s bedroom to retrieve them, sidestepping music sheets and books and clothes. “How you manage to emerge from this…” she would say, somewhat exasperated, looking about and holding out her hands as if to receive piles of dirty laundry in her arms, “… is beyond me.”

“Don’t know, Mum … just do.”

“You’re like a butterfly coming from a cocoon.”

“Yup.”

“Mother find mugs?” Her father would ask when she hopped into the car later, not a minute too soon. He’d be sitting, waiting patiently to drive them: she to school and him to work.

“Three.”

“Not a record so. You could make her happy, if you wanted,” he said, looking at Rose seriously for a moment, “by giving your room a little tidy.”

“I know, Dadda. I’m sorry.”

“Was she cross?”

“No. Not really.”

Back then, Rose was at secondary school, and Luke’s law office was in the town near the old limestone courthouse. It was a daily ritual. Rose was always only just on time. Her father was the kind of man who felt being exactly on time was already being late. So in order to avoid the kind of confrontations Rose and Iris sometimes had—it being only natural with two females in the house—he allowed her to think he needed to be at work twenty minutes before he did. It was easy for him to make allowances for his daughter.

A breeze stirs, the curtains move a wind chime. She plans to phone her mother later to say her room was flooded with light when she awoke. That’s what she will tell her—there was a song outside my window, Mum.

Grabbing a pair of jeans, Rose lifts a gray cotton string top from among small piles scattered across the floor. She grabs a black cardigan and turns to her image in the mirror. She decides not to braid her long hair but tucks loose ends behind her ears. “Rosie dear, please tidy your room, soon. Now, there’s a good girl.” She carefully folds a black jersey dress and slips it into her rucksack.

The sitting room is strewn with her roommate’s tissue-paper patterns and toiles. In the corner a tailor’s dummy is half-dressed with a print chiffon. “Hello, Dummy.” She writes a note and pins it to the dummy’s breast.

Isobel, gone to master class. Wish me luck! Talk later. x Ro

The Pirate Castle at Oval Road on the edge of the canal is below her flat. The stairs alongside it are iron-rusted and gum-stained. A paper cup sails on the gathered green algae. Rose now walks along the narrow sidewalk, dodges cyclists coming toward her, and hurries under the dark part of the railway bridge. She passes the floating Chinese restaurant at the canal’s turn at Regent’s Park, where she joins the stream of morning commuters and dog walkers.

This morning, Tuesday, the grass verges of the Broad Walk in Regent’s Park are flaked with pink droppings from the horse chestnut trees. Blossoms pirouette in the wind. It’s snowing petals. For a moment she stands, closing her eyes, waiting for one to hit her face. She’s a girl standing still in the green heart of the moving city. She opens her mouth and sticks out her tongue to catch a petal and taste its pinkness, but without luck.

The petals toss about in whirlwinds while she continues along at the edge, where the grass meets the pavement. Two petals land on the back of her head, wed themselves to her dark hair. There’s a man in a smart suit walking beside her, and he looks as if he wants to say something. She’s seen him before, on the daily commute through the park, one of those familiar strangers in our lives. But he doesn’t speak. Rose hoists the weight of her case on her back from one shoulder to other. The businessman follows a few paces behind.

Rose is humming as they cross Chester Road, and she turns slightly right to walk along the western side of the Avenue Gardens, passing the colorful parrot tulips. At Park Square she turns right again in the direction of Baker Street and the Royal Academy of Music on Marylebone. The man pauses. He stops to watch her. She is like a picture of a girl in painting. The petals adorn her hair like gemstones as she heads up the steps of the academy.

On the top step she turns, pauses momentarily. The young businessman crosses the road and walks east toward Portland Street. Another time, she thinks. Today is not the day. No. Today’s agenda is already full. No room for flirtations. She’s having a master class with Roger—Mr. Kiwi Dude, as some of the other students call him—in the afternoon but has one last practice with him this morning. She passes the porter. His crooked lips ignite into a smile.

“Miss, you forgot to sign in.”

She spins around and returns to his desk. “Sorry, George.” She signs. She senses his glance at the birthmark on her cheek. He can’t help himself. Rose knows; she’s used to it. She’d decided at the end of her teens not to keep trying to cover up the small, darkened stain and so, as she signs her name she smiles, hands the pen back to George.

“There you go.”

When George returns his eyes to the desk a pink fragment has appeared, like a thumb-size piece of silk, on his record book. As Rose moves off down the hallway the old porter shifts the petal to beside the girl’s name.

Mr. Kiwi Dude is a handsome New Zealander and a virtuoso violinist. In addition to giving master classes, Roger Ballantyne is Rose’s tutor at the academy. She’s lucky. He used to play with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra before moving to London to take up the professorship in strings for second-year students. He isn’t one of the stuffy types they have there. He’s cool, the type of not-quite-fifty-year-old who looks not-quite-forty because his skin is permanently tanned and his curly hair is hardly gray. It has sun-bleached highlights. Does he dye it? Now that would be cool. Rose heard a segment on BBC radio about men wearing makeup. And why not? That would have made her father laugh. Too bad Dadda would never know things like that, like how she feels about men wearing makeup, or how she loves to take the tube around London, finding her way to places like Columbia Road Flower Market in Shoreditch, or discovering random hidden gems like the Fan Museum in Greenwich. Sometimes she visits the British Library just to see what’s on in case it’d be something her father would have liked. She knocks on Roger’s door.

He opens and holds it. He’s wearing flip-flops and jeans and a brown T-shirt with the logo of a white wineglass. “Hey, Rose. Come in.” He steps aside. “Excited?”

“Hi. Yeh … I am. Nervous, though.”

“No worries … you’ll be fine.”

Rose senses something about him is off but she continues, “I’m scared, actually, and feeling kinda hyper.”

“Your final master class can do that, but it’s the end of a great year, Rose. You’ve done well so far. Don’t be worried.” He looks at his cell phone. “Anyone in your family coming to hear you today?”

“No. There’s only my mother and she’s in Ireland. I told her it was next week. She gets too anxious for me. I’d be more worried for her being worried for me than I’d be nervous to play.”

As if he really wasn’t listening, he says, “Maybe next year.”

On the wall of his small office there is a poster of a surfer on a wave. Rose lays her case on a chair below it, unzips the cover, and undoes the clasps. Her violin lies open with a mottled layer of white just under the bridge. Crap. Light from the window overlooking Marylebone shines on the varnish as she takes her instrument up by the neck. Tiny specks of rosin run off the surface. As she bends slightly to position herself, the second pink petal falls from her hair onto the floor. Rose only notices the shower of rosin.

“That dust I’m seeing, Rose…” He pauses. His fingers are tented under his chin. He taps them lightly. He looks at her like she’s a child. And the look makes her feel like one. “Rosin won’t make you play better, you know. Here, give it to me.” He takes her instrument and wipes the excess with the cloth he keeps on his music stand.

Rose gets her sheet music and sets it up. The excitement of the morning is gone. Her head is a jumble. The sheet music trembles as she adjusts it on the stand.

“I was practicing last night. It was late.” She feels chastened, embarrassed. Her fingers have a clammy mind of their own as she takes up her bow and tightens it.

When Roger hands back her instrument he is not pleased. “Begin with a G-minor scale, please. Three octaves.”

Roger “the master” is preparing Rose for her first solo performance of Bach’s Sonata in G Minor. Serious stuff, she gets it, but this coolness increases her anxiety. What the hell? The student recital and master class is scheduled for the afternoon. Roger’s other students will be there. Some performing. Some not. Maybe he’s anxious, too. She lifts her violin with her left hand and brings it to her shoulder. Is he angry with her? It wasn’t that much rosin. Her chin senses for the familiar place on the rest and nestles into position like a cat finding a place in the sun. She bends her fingers and squares them, placing them in position for the scale. With her bow raised she takes a moment, counts to three, scans the room: the poster, the warm light that angles in from the window, Roger standing beside the door, his arms crossed over his chest. She begins. G A B flat, C D E flat, F G …

“Good,” he says. “Again.”

Again Rose plays. She relaxes and thinks, Okay, I’m feeling more confident now. Her old teacher, Andreas, appears for a moment in her mind.

“Ready?”

“Yes.”

“Begin.”

With the top of the bow hovering just a whisper above the strings, she nods imperceptibly to the surfer and begins the adagio, the first movement of the sonata, with a sweeping run into an arpeggio starting with a slow bow.

Everything is good, Rose believes. She’s relaxed. She’s playing really well. Somewhere near the end of the second movement, the fugue, Roger’s cell phone rings.

It rings once.

She plays on. He’ll silence it in a second. She’s into the challenging ascent, and is careful not to lose the singing line, the melody line, but the damn phone is still ringing.

A fifth ring. A sixth. And then he answers it.

He opens the door and he goes out into the hall. He actually walks out. Worse, he gives a slight wave of his hand in her direction indicating she should continue playing. The door doesn’t quite shut. It hangs ajar and she can hear him in the hall.

“Ah. No. Don’t do that. We can meet later. I know. I know. Hey, why don’t you come, it’ll be fun. What? No? We can go for a … no. Please … Victoria?”

Silence.

Then, “Fuck!”

A sharp thud thunks against the door.

Rose plays on, by now just beginning the third movement, the Siciliana. She plays it slow, emphasizing the dotted rhythms like Roger has shown her. After a few minutes he opens the door and walks behind her to the window without a beat of acknowledgment. She keeps playing. This movement is melodic and Rose is swaying. But suddenly he stops her, puts up his hand, and says, “You’re not moving slowly enough into the strings. Approach it from underneath. And … re-lax … the tension in your left hand.” He checks his watch. “I’ve told you that before.”

Rose lowers her violin and bow. Her head is turned slightly, her small birthmark fully visible. She’s uncomfortable with him, with the way he’s looking at her. She’s suddenly very self-conscious. They stand facing each other but saying nothing. He turns back to the window. Sounds of buses rise into the stillness of the room.

“I can’t do this now,” he says, and walks past her. Out. It happens in a second. She hears his footsteps flipping and disappearing down the hall and down the stairs.

Rose stands, holding her violin and bow at her sides, closing in on herself like she’s a deflated party balloon. She stops breathing and listens. She expects he’ll be turning around, turning around any minute and coming back. Coming back to apologize, or something—to hear her finish the Siciliana at least.

She waits, waiting to be revived, but he doesn’t return. She stands at the window, bow in one hand, violin in the other. Roger has left the building. She sees him crossing the street and heading down Thayer.

“Feck!” she says. “Crap!” A wave of bewilderment quickly turns to something else. Part of her feels frozen, part of her feels fuming; her movement is jerky as she starts to pack up her bow and violin. She’s shaking between anger and humiliation.

Before closing her case she eyes the slip of paper taped to the inside velvet covering, the one Roger had given her the first day she started practicing the sonata with him.

Rose,

Practicing Bach for me is like a meditation, even a daily prayer. It connects me with a higher power. May it be the same for you.

As ever,

Roger

She pulls it off the velvet, crumples the note, and throws it down.

Still shaking, she stands in the corridor outside his office.

With a little over an hour to pass before the master class, she hopes she’ll run into someone, anyone she can vent to, but the hallway is empty. She thinks about finding the two friends she’s made at the RAM. Leonard and Freya. They’re studying musical theater, but they have their final projects this week, too. There are only the muted notes of string-playing instrumentalists she can hear behind the closed doors of the small practice rooms. Ysaÿe. Kreisler. More Bach. Rose slumps down against the wall. She feels like vomiting. Do they all play better than she does? Today was meant to be a celebration. She was looking forward to performing, to staking out her territory, to claiming her place alongside the other brilliant students in her class, and to ringing her mother with triumphant news. Now she feels cast out, inadequate. An amateur. A craftsperson at best. Not an artist. She makes no sound in the hallway although tears shine in her eyes.

A door opens and closes somewhere down the hall. What is she going to do now? Hang out here until Roger returns?

What the hell?

And who is Victoria?

In the ladies’, she sees her red face in the mirror. She stares while trying to control her breathing. She’s gulping for air.

Finally, she takes out her makeup bag. The birthmark is flushed with feeling. She looks closely at it, as if in seeing it, it somehow pulls her back into herself and she begins to calm down.

“It’s shaped like a rose,” her father said.

“A tiny tea rose,” her mother said.

When she was old enough to understand such things, they had told her: “That’s why you were named Rose.”

She’d thought about that for a moment and then asked: “What if it looked like an elephant? What would I have been called then?”

“Ellie, of course!”

They went on like this, making a game of it. The story of the rose always preceded the story of how she arrived in Ashwood on August 23, 1990, when she was eight weeks old. She wasn’t an orphan, but “placed” for adoption following her birth in the month of June. Both stories always worked to make Rose claim her identity. Her father was right, the edges of the birthmark on her right cheek do look like the curved petals of a rose tattoo. But that’s not why they named her Rose. She knows that. But the story always comforts her. She’s grown used to it, just as she’d grown up with the idea of being adopted. Just another way of being in the world. Most of the time she doesn’t even notice. It doesn’t really matter, most of the time.

When she was sixteen her parents decided to give her the letter from her birth mother. She had cried when she read it. Rose keeps the letter tucked inside a music book that is on the shelf in her bedroom back in Ashwood. Her birth mother hadn’t written much. It was a short, handwritten letter. She wanted Rose to know she was very much loved and it was because of that love she’d been “placed” with a wonderful couple who would give her all the things she couldn’t—a house and home and, most important, two parents who really loved each other. Always remember you are doubly loved. By me, forever, and by your parents.

She touches her cheek and thinks of her father. What would he do now? She knows her mother would be raging mad at Roger. In fact, now that she thinks about it, she’s sorry she didn’t tell her mother the master class was this week, because if she had, her mother would be on her way to the academy, bursting in without stopping for George, marching right up the stairs to the office of Mr. Roger Ballantyne and waiting for him to come back, to ask him what the hell was he doing walking out on her daughter at a critical moment when she was trying so hard to be perfect. She would be a storm coming at him. And for a moment Rose lightens up just thinking about her impassioned mother.

But her father, now what would he do?

Leaving the makeup bag on the edge of the sink, Rose takes out her ensemble for the concert, strips off, and steps quickly into her sleeveless black dress and ballet flats. She returns to her makeup and underlines and overlines her eyes in black. Sultry.

Feck ’em. Get your Irish up! her father would have said.

Yes. Feck them.

She picks up where she left off with the Siciliana. The acoustics in the ladies’ room are amplifying. Her Siciliana is a long, anguished sigh. She leans into the phrases like Roger taught her, goddamn him, giving them room to breathe without letting them fade like petals withering on a stem. The heartbeat in her chest is a metronome, silent to the outside world, but keeping time with the music.

* * *

An hour later, she gets her Irish up and goes to the recital hall. Roger returns five minutes before the master class and just nods to her as if nothing has happened. He doesn’t offer any explanation or apology. She opens her case and gets ready. She’s up first. Bowen before Ferguson and Kowowski. She steps to the stage in a sort of half dream. Dust motes swirl in the glare of the stage lights. She doesn’t look out at the audience of fifty or so. She doesn’t want to see the gathered students and their parents and the other professors come to assess the best of the academy’s talent. She settles her chin and begins. She plays her heart out. She keeps the melodic contours without losing the balance. Her phrasing is intense but elegant. She is playing it beautifully.

But she is wrong.

“Wrong. Wrong. Wrong,” Roger Ballantyne says, taking center stage. “Stop moving, Rose. You look like you’re trying to draw pictures with your scroll.” He looks to the audience, as if he’s said something clever. “You are playing too fast between the sections. Wait … until … the sound … comes out and we can hear the change of colors.”

She continues. Louder. But over her playing, he is calling, “Don’t be so polite. It’s Gypsy music! Play it like it was written.”

She plays. He is strutting on the stage. “Your vibrato is exaggerated.”

She tries to exaggerate less.

“It sounds like you are ironing the strings. Rose!” There’s an actual murmur from the audience. Stifled laughter? “Make them sing like a song. Let them breaaaaathe.”

Roger crosses the stage and picks up his violin. “How you manage to make Bach sound sterile, I don’t know.” Rose stops as Roger starts into the fugue, to demonstrate. He’s superb, of course, and when his attention is focused on the audience, lost in his own magnificence, Rose grabs her case, violin, and bow and walks out. She doesn’t look back and she squeezes her tears. She hopes for one moment Roger will call after her, she hopes he will stop performing and call her back, that he will feel her humiliation. But he doesn’t. Murmuring from the audience doesn’t stop him. It’s all about him. He has his audience, and plays on.

The next moment Rose is into the cool corridor. She kneels down and puts her violin in the case, then gets up and keeps walking, pushing out the front doors until she is out onto the rainy, steamy street. Too wet to walk back to Camden.

* * *

Five o’clock and the mood of the crowds on the busy night on Baker Street is a clash-and-bang cacophony. Rose jostles her way to the tube platform, barely conscious of where she is. She stands, hollow and waiting. When her train comes she steps inside just as the doors close. They catch her violin case. She tugs it free and loses her balance. A man beside steadies her. Collapsing into a seat, she hoists the case onto her lap and stares at the black mirror of reflected faces and lights as the train whirs through the tunnel. At King’s Cross she gets out to change to the Northern Line. Up the escalator, a hundred bodies judder as one, except for Rose Bowen, who stands immobilized, apart, void of thought or emotion. Euston. Mornington Crescent. Rose gets out at Camden. As the train pulls away, she stands on the platform and looks back into the carriage. The doors close and when the train shudders into motion, she watches her violin topple from where she has left it leaning against the window. It slides down onto the seat. Then off it heads. Chalk Farm, Belsize Park, Hampstead, Golders Green, Brent Cross, Hendon, Colindale, Burnt Oak, Edgware.

Gone.