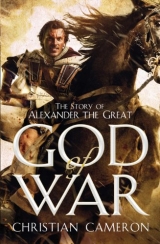

Текст книги "God of War -The Story of Alexander the Great"

Автор книги: Christian Cameron

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 58 (всего у книги 62 страниц)

The enemy threw in their last line of cavalry, and the whole melee shifted again, and I was facing a sea of foes.

Elbow to elbow with an Indian – we both cut, and his sword bent, but my beautiful Athenian kopis snapped at the hilt. He leaned back to cut at me, and I got my bridle hand under his elbow and then punched my right fist and the stub of my blade at his face until the blood gouted and he was dead. He fell into the sea of horses and was swallowed up.

And then, with a roar like a river in flood, Coenus fell on their rear.

Obedient to the king’s orders, he had ridden all the way around our left, and around the rear of the enemy, and now he fell on the cavalry melee with the finality of a lion bringing down an antelope.

The Indian cavalry broke in every direction. And the battle was won.

Unfortunately, no one had told King Porus.

As Porus’s cavalry streamed from the field with the Hetaeroi and the Persians in pursuit, the phalanx, formed at last – we’d been stades ahead of them on to the field, and our charge had been swift – elected to advance. I assume that Perdiccas thought to take advantage of the chaos of our cavalry victory to press Porus right off the field.

Alexander had given the pikemen a brief pre-battle speech, or so Perdiccas told me later – on how invincible the pike was.

When you are a god, men believe everything you say.

The wall of pikes and shields pressed forward down the field.

Porus – a giant of a man, seven feet tall, on an elephant that towered almost a full head above all the other monsters on the field – didn’t even glance at the wreck of his cavalry. He raised his goad, and his bull elephant trumpeted – a sound that reached above the neigh and screams of horses and men – and his crenellated line began to move slowly down the field towards our advancing phalanx. I could see him, about two stades away, and he looked huge at that distance.

Let no man doubt the courage of the Macedonian phalanx. Faced with a line of monsters, they walked steadily forward. For the first time in years, they sang the paean – we’d never had a field to sing on, in Sogdiana.

I was rallying my squadrons. I was never the strategos that Alexander was, but I had enough sense to see that our infantry might need help, and that help would have to come from the cavalry. But it was a mess – the Indian cavalry had mostly cut and run, but we were dreadfully intermixed, my front squadron had threaded through Coenus’s front squadron, and all the trumpets were sounding the rally. With the cries of the elephants and the tortured sounds of wounded animals, it took the will of the gods to get a man back to his place in the ranks.

I watched the two mighty lines close on each other. I waited for one or the other to flinch.

No one flinched.

When they met – when they met, it turned out that Alexander was wrong about the efficacy of the pike.

A lot of our men died, in the front rank. Veterans – men who had crossed the Granicus, men who had stood their ground at Chaeronea, stormed Thebes, crossed the Danube . . .

The men who made us what we were.

They died because elephants cared nothing for age, skill, armour, shields or the length of the spear. They snapped the spears, and their great feet crushed men, and their trunks grabbed men from their ground and lifted them high in the air, and their tusks, often sawn short and replaced with swords, swept along like the scythes on Darius’s chariots.

The taxeis were not in the same state of high training they had once been. The ranks were full of recruits and foreigners. When the phylarchs ordered whole files to double to the rear to make lanes, some taxeis, like that of Perdiccas, executed this flawlessly, and the monsters walked on, doing no harm. But in other taxeis, the attempt to manoeuvre in the face of the beasts led to chaos.

And collapse.

Meleager’s taxeis broke first. It didn’t run – because the better men weren’t capable of running. But the lesser men hesitated, the files fell apart and then suddenly the pikes were falling to the ground and men were falling back, or running, leaving their phylarchs and their half-file leaders to fight alone.

Attalus’s mob broke next. They unravelled faster, and by the time they started to go, I was in motion. I looked back for the king, and I couldn’t see him, so I acted on my own.

I led the Prodromoi forward into the flank of the Indian line. It wasn’t really a lineso much as a thin horde. They were having trouble with their bows, which probably saved a lot of Macedonian lives, but they didn’t have any trouble with their long swords, and they were using them to batter through the front of the spear wall, where the elephants caused any hesitation.

Right on the end of their line, closest to me, was a hard knot of elephants – five of the brutes.

We charged them.

Our horses baulked.

A mahout swung his animal to face us, the men on the animal’s back showering us with darts and arrows. Above us in the swirl of a cavalry fight, they had a superb advantage. It is very hard to throw a javelin up. Especially when trying to control a panicked horse.

Indian cavalry had taken refuge with their elephants, and their horses weren’t panicked by the monsters – a matter of habituation.

An old Thracian, Sitalkes – I’d sat around a hundred fires with him – downed a mahout with his javelin. Most of the Paeonians saw it, and the cry went up to kill the drivers – because no sooner did the mahout fall from between the giant beast’s ears than the animal came to a dead stop.

But it was easier said than done, and most cavalrymen had only two or three javelins, and most had spent them in the cavalry fight. Before long, we were riding in among the animals, but doing them no harm – washing about their feet as the ocean washes against the pilings of a pier.

I rode clear of the fight.

There was the king, rallying his household Hetaeroi.

I rode up and saluted. He bellowed at his trumpeter, Agon – the same man who refused to summon the guard the night that Cleitus died, a fine man and a hero many times over – bellowed for Agon to sound the rally again.

He looked back at me.

‘We’re not having any effect,’ I shouted. ‘We need javelins. Youneed javelins. And the beasts panic our horses.’

Alexander watched the melee behind me for the space of twenty heartbeats.

‘Not true,’ he said. ‘Your men have pulled five elephants out of the line. That’s something.’

‘What do we do?’ I asked.

Alexander backed his beautiful white horse – his fourth mount of the day – and fought the stallion’s desire to fidget. ‘I’m thinking,’ he said.

From any other man, that would have promoted panic.

I turned my horse, intending to go back into the melee. Not because I wanted to. Fighting elephants is pure terror – fighting them on horseback is fighting the monster, fighting your own fear and the fears of a dumb animal who controls your fate.

Alexander grabbed my shoulder. ‘Stay,’ he said. ‘I need you.’

So I waited.

I had never had leisure, in the middle of a fight, to watch him. I had seen him at the height of battles – but never at the height of a battle in the balance.

He rode back and forth in front of the Hetaeroi. He was learning his mount – he walked, he trotted, he sat back, he rolled his hips. Meanwhile, his men were collecting javelins from the ground, and from corpses, and the last slackers were rejoining.

To our front, the elephants were surrounded by the Paeonians and the Prodromoi. Men were trying to cut the elephants with their swords, and failing. They were brave.

They were dying.

Beyond them, the elephants were pressing forward. Closest to me, Seleucus and the hypaspists were retiring slowly, in perfect order. A dead elephant testified to their prowess, and the Indians let them go.

They were retreating because the phalanx was gone. The five taxeis were huddled in the scrubby trees.

Porus and his elephants rumbled to a stop. His Indian infantry didn’t leave the shelter of the great beasts. They reformed their line and began to loft arrows at the hypaspitoi, the last infantry on the field.

Alexander grabbed my bridle.

‘Go to the centre and rally the phalanx,’ he said. ‘Get them back on to the field. They will not want to come. Make them move.’ His eyes glinted like polished silver, and he was smiling inside his helmet. ‘Look at the five monsters you charged.’

One elephant had simply wandered away, its mahout dead. The other four had stopped. They were confused by all the horses, by the pain of a thousand minor cuts, and now they were baulking at their mahouts’ commands, turning and moving away, into the flank of the Indians. Killing their own men.

‘Get the centre back,’ he said. ‘I’ll defeat the elephants.’

He sounded very, very happy.

I rode to Seleucus, first. He was on foot – his horse had dumped him as soon as the elephants closed, a young horse and not fully broken.

He looked stricken. ‘We . . . we’ve lost?’

I managed a smile. ‘Look at the king,’ I said. ‘Does he look beaten?’

Seleucus nodded. And grunted.

‘I’m going to try to get the pezhetaeroi back on the field,’ I said. ‘Retreat slowly, and when the centre comes back, go forward.’

Alectus laughed. ‘Forward, is it?’ He pointed at a pair of elephants, tusks dripping. They had a hypaspist – both had their trunks around him – and they were both pulling. Pulling him apart. Like cats playing with a mouse.

‘Forward when I come,’ I said.

I spurred Triton, who was delighted to ride awayfrom the beasts.

Back among the scrub, there was a sight I had never had to see. The pezhetaeroi were angry, terrified and humiliated. Men were sitting on the ground, weeping, or staring dumbly. A few phylarchs were trying to form the men, but most were standing, watching disaster without any idea how to fix it. Rout was something that happened to other armies, not ours.

And a lot of our phylarchs were dead.

Meleager was at the rear of the mess, out on the open ground north of the woods, hitting men with the flat of his sword, herding them back into the woods.

I rode to him. ‘Alexander says get them back into the field,’ I said.

Meleager looked at me. ‘Fuck you,’ he said. ‘They’re not going, and neither am I. Why don’t you go and face the elephants, and see how you like it?’

‘I already have,’ I said. ‘I can’t pretend I like it. But I’ll do it. And so will you.’

Meleager spat. ‘Fuck off,’ he shouted.

I left him to his despair and rode to Attalus.

Attalus had the nucleus of his taxeis formed behindthe woods, and more men were joining the ranks, and the surviving phylarchs were appointing new file leaders. The awful truth of a rout like that is that the best men die. They’re the ones who stand. The lesser men run, and survive.

‘Alexander orders you back on to the field,’ I shouted.

As soon as men heard me shout, they started walking to the rear.

‘Are you insane?’ Attalus screamed at me. ‘It’s all I can do to hold them here!’

I rode on.

Just beyond the wreck of the phalanx, behind the centre of the woods – open oak woods, here – stood an island of order. Briso, with the Psiloi – the archers, the Agrianians. Right where I had left them.

‘Trouble?’ Briso asked.

Three hundred archers and six hundred Agrianians. And sixty of Diades’ own specialists, the bowmen carrying gastraphetes and oxybeles, the two-man crossbow, under Helios.

I motioned to Attalus – the Agrianian Attalus, not the Macedonian one. I slid from my horse’s back, and my muscles screamed in protest. There’s nothing worse – to me, because I am just a mortal man – than leaving combat, and then having to return to it. I had been in a mortal fight, survived, triumphed, faced the monsters and survived again. And now I had to steel myself to go back. Again. I had to lead other men.

I took several breaths while I dismounted. Then, to goad myself, I took my helmet off – my beautiful Athenian helmet – and threw it away. I needed a clear head and good vision.

Ochrid had followed me all morning, and now he appeared at my side and I took my two best javelins from him. Their blue and gold magnificence steadied me. It sounds childish, but their octagonal ash shafts were friendly to my hands.

I nodded to my officers.

‘We’re losing,’ I said.

They all looked as if I’d punched them.

‘Don’t fool yourselves,’ I said. ‘If we don’t do it, the army is done. So we’re going to go right up the field into the teeth of the fucking monsters and we’re going to kill them – close up. With everything we’ve got. If we can get in close, maybe the gastraphetes can shoot the monsters. Helios, that’s your job – to get the machines as close as can be managed. Attalus, cover the archers and press forward – right into them. We’ll go in among their legs and try for the crews. The mahouts – the drivers – are vulnerable. Get them. But mostly, don’t let the beasts into the archers.’

I looked at them. They were scared. That was fair enough – no one had ever faced anything like this before. And I was about to lead a thousand men to do what twelve thousand had failed to do.

‘We can do this,’ I said. ‘The one thing I’ve learned today is that the beasts are slow, and tire easily. If we have to retreat – then we’ll run.’ I moved my eyes from face to face. ‘And go back. Until the king has his counter-punch ready.’

Briso nodded, and Attalus took a deep breath, and Helios looked thoughtful.

‘We’re all he has left,’ I said.

That stiffened their spines.

Attalus formed the Agrianians in a long skirmish line behind the woods, and the Toxitoi formed behind them – one long, long rank, three hundred men long, with a horse length between men, so that our whole front covered six stades – almost the frontage of the phalanx. The crossbowmen stood in knots, or as individuals, where Diades assigned them, well behind the skirmish line.

We moved through the woods – and the wreck of the phalanx – to the sound of the hunting horns.

My last act before we went forward was to send Ochrid to the baggage with orders to fetch more bolts, arrows and javelins. Then I remounted, so that I could see to give orders, and followed.

The phalangites in the woods were angry, and they jeered at the Agrianians and the Toxitoi, taunting them that they were going to their deaths.

At the forward edge of the woods, the better men crouched and watched the enemy. Most of these men still had their sarissas, and so had never entered the trees.

And there was Amyntas, son of Philip. He had a nasty face wound – the skin on his scalp was ripped and his helmet was gone. But he had his aspis and he had his spear.

I raised my javelins to him.

‘Dress the line,’ Attalus roared. The hunting horns gave their low, mournful call.

The Agrianian line trotted out of the edge of the woods. The Toxitoi emerged behind them.

Amyntas trotted to my foot. ‘You are going forward?’ he croaked.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘If you can form any kind of a line, follow us.’

He nodded. He never really looked at me. His eyes were on the enemy.

‘Alexander says we are not beaten yet!’ I turned to the men hesitating at the edge of the woods. ‘Follow us. Form the phalanx. Let the Psiloi hurt the elephants. Come and protect us from the Indians. Come and be men!’

Men looked at me, and looked at Amyntas.

And stood where they were.

My curse on all of you, I thought.

And I went forward with a thousand men, to face the elephants.

It is very lonely, as a Psiloi.

There’s no comfort from your file mate, because he’s a horse length behind you. No comfort from your rank partners, your zuegotes, the men you are yoked to in the battle line. They’re too far away to touch, to look in the eye, to wink at or to moan at.

I had never realised how very brave the Psiloi were, until that day, against the elephants.

The Agrianians went forward fast, at a trot. The Indians made the same mistake we’d made. They thought that the battle was over. And they were probably contemptuous of the thin screen trotting down the field towards them.

I was huffing by the time we came within a long javelin throw of their line. The Agrianians, obedient to the shouts of Attalus, began to gather in loose clumps facing the pairs of elephants. They ignored the Indian foot soldiers and ran straight to the elephants.

The Indians began to loose arrows, but their aim was poor. Skirmishers are a difficult target for massed archery – especially skirmishers making a concerted dash forward.

The men they hit died, however. Their arrows were enormous.

Archers on the backs of the elephants shot, too.

The Agrianians went forward into the arrow storm, heads up, legs pumping them forward. Right into the monsters.

Off to my right, the hypaspitoi watched us come up, pass their front and move on. They cheered us, but they didn’t follow.

Farther to the right, I could see the king – far, far off, gleaming on his white horse. He had formed the Hetaeroi into four wedges, and that’s all I had time to see.

‘The king is coming!’ I called.

And then the Agrianians went in among the elephants, and the madness began.

The Indian infantry stopped being stunned by our reckless approach – really, a charge – and started forward, eager to crush our Psiloi.

I put my bare head down and rode for the hypaspitoi. But Seleucus waved me off, and I saw him march off his half-files to the left, doubling his front, and then the whole of the hypaspitoi started forward at the Indian infantry. They, naturally enough, flinched, and responded to the charge of the hypaspitoi.

Triton had decided that he could survive facing elephants. He shied, but he went where I pointed him, and now I pointed him at the largest struggle – fifty of my Psiloi and twenty archers against five or six elephants right in the centre of the field.

There were Paeonians there, too, because the Prodromoi and the Paeonians had filtered all the way along the Indian line by this time – the battle was breaking down into a desperate, every-man-for-himself engagement of a kind I had never seen. The Indians were surrounded, but so far their monsters were untouchable.

Even as I watched, an Agrianian punched his heavy javelin into the side of one of the towering beasts, and then threw himself at the shaft, stabbing deeper and deeper. The great animal bellowed, and its trunk licked out and caught him and ripped him free, throwing him over its head – but another man had a shaft in, and a bold pair of Toxitoi stood almost at its feet and shot – shot quickly and accurately, despite the bestial death that towered over them, and they cleared the crew off the beast’s back, and an engineer leaned in, almost touching the animal, and his bolt vanished into the behemoth’s guts and the animal screamed in agony.

The archers shot into its face, and their shafts bounced off its thick skull, and then a lucky shaft, Athena-guided, or moved by Apollo’s hand, went into an eye, and the creature stumbled, bowed its mighty head and slumped to its knees.

The other animals nudged it – it was somehow more horrible than anything to see their concern for their fellow monster.

And then they shuffled their great, flat feet and moved back, away from the pinpricks of the Psiloi.

I rode back down the field to the pezhetaeroi. ‘Come on, you bastards!’ I shouted.

And they came.

Meleager had a handful, when he first started back up the field. Antigenes and Gorgias had even fewer.

But Philip son of Amyntas, senior phylarch, had a lot of good men – men of all six taxeis. He ignored the officers. His full-throated roar was as loud as an elephant’s scream of pain, and carried across the field.

‘Get in the ranks! Get in the ranks! Pick up any spear you see and get in the fucking ranks! Are you cowards? Are the fucking barbarians better men? Are the archersbetter men? Get up!’ he screamed. Spittle shot from his mouth as I rode up to him, and he ignored me. ‘Get in the ranks! Fill in! Now. The king needs us!’

And they came.

They came in tens, and then they came in hundreds, and then it was like an avalanche of pikemen. They came with swords, with daggers, with broken spears, with stolen javelins, with bare hands.

I had never seen anything like it.

Gorgias and Meleager ran to the front to take command, but I cantered past them to Amyntas son of Philip.

‘Into the Indians!’ I shouted. ‘Stop their gods-forsaken archers from coming to grips with the Psiloi!’

He put a hand to his ear – an ear covered by the flaps of his helmet.

‘Forward!’ I shouted.

He grinned. It was a hard grin – an evil grin. ‘Here we come,’ he growled.

I galloped back to the elephant fight. Dozens – in some cases hundreds – of Indian archers were clearing our Psiloi off the beasts, pushing our men back, and back.

Until the hypaspitoi and the phalanx struck them, and crushed them. In three hundred paces, the battle was transformed and the Indian archers broke, running for the safety of their elephant line, which had retreated several hundred paces, the great beasts lumbering away and putting heart into our phalangites.

The Psiloi ran down the gaps between the taxeis, and reformed in the rear, drinking from canteens, and slumping to the ground in blank-eyed exhaustion. They had faced the monsters for about as long as a man and a woman make love. No longer. And they were spent.

Nonetheless, Ochrid arrived with a train of slaves bearing arrows, javelins, bolts and darts.

Briso was missing. Attalus was badly cut by a sword, and Helios was commanding all the Psiloi. I waved a javelin at him in thanks. ‘I think you’re finished,’ I said.

His look of relief said everything.

I turned Triton and rode for the front.

There was almost no fighting. The Indian infantry was lightly armoured and when they ran, our men couldn’t keep up, even if they broke ranks. All along the front, our men reclaimed fallen spears, some picking up shields. To be honest, men were stillcoming up from the woods, convinced by the victory that it was safe to emerge from their cowardice.

They were wrong.

Porus wasn’t beaten. Porus was regrouping.

The king had begun to throw his wedges into Porus’s flanks, but Porus, with real brilliance, countered them with elephants, sending companies of elephants into the point of the wedges, shredding their formation.

He had saved a squadron of giant chariots, and now he released them against the king’s flank, but that, at least, we were prepared for, and Alexander sent his tame Saka, Massagetae who had taken service and Sogdian nomads, to shoot the chariot horses. They destroyed the whole force – a thousand chariots – before the infantry had time to panic.

But, Porus rallied the bulk of his elephants, and placed himself in the centre. Any infantry that could be rallied – and they were brave men, those sword-armed archers – came forward on the flanks of a veritable phalanx of elephants, with the giant of giants leading the way.

It was a slow attack – scarcely a charge, but a shuffling, lumbering advance, slower than the march of a closed-up phalanx.

But our men were not going to stand it. They began to shuffle back.

And then the king was there.

He appeared out of the woods, and he rode unerringly to Amyntas’s side even as I reached him.

‘The infantry!’ he said. He smiled. ‘Just hold their infantry. Oblique right and left from the centre – avoid the elephants.’ Men heard him. The words ‘Avoid the elephants’ were wildly popular.

And his presence was like a bolt of energy.

The retreat stopped.

I remember the king looking at Meleager, who was not in the front rank, not in his proper station, and clearly not in command. His glance only lasted a heartbeat. He didn’t show anger, or pity.

Just a complete lack of understanding, like a man facing the sudden appearance of an alien god.

Then he turned his horse.

I didn’t wait for him. I knew what he needed. I just waved.

And rode for Helios.

‘One more time!’ I called.

Even the Agrianians – the bravest of the brave – shuffled their feet.

There are times when you yell at troops, and times when you coax them.

And sometimes, when brave men have already done all that you can ask – all you can do is lead them.

I rode to the front of them, and I raised my javelins, as yet unthrown, over my head.

‘I’m going,’ I said. ‘Do as you wish.’

And I pointed Triton’s head at the elephants and walked forward.

I didn’t look back. I had time to think of the hill fort, and the taxeis that left me to die. The Agrianians were men I’d served with for years – but they weren’t mine. I was best with troops who knew me. I didn’t have the magic Alexander had. I was the plain farm boy, and it took men time to love me.

So I let Triton walk forward, and the elephants were close – fifty of them, formed in a mass.

The phalanx had broken in two, and each half marched obliquely to its flank – or flowed that way like a mob. Discipline was breaking down. It was already the longest battle any of us had ever seen, and darkness was not so very far away, and the main lines were on their third effort.

There would be no fourth effort.

This, then, was it.

Alexander appeared at my bridle hand. He was smiling, and the sun gilded his helmet. He pulled it off his head, and waved it. ‘Nicely done, Ptolemy,’ he said, his eyes on the men behind me, who were following, formed in a compact mass roughly the width of the elephants to our front. The Toxitoi and the engineers and the Agrianians were all intermixed.

To my left, Amyntas was leaning forward towards the enemy as he walked behind his pike-head like a man leaning into a wind. To my right, Seleucus was almost perfectly aligned with us.

I could see men I knew, and men I had never seen before – Macedonians and Ionians and Greeks and Persians and Bactrians and Sogdians, Lydians, Agrianians. I think that I saw men who had been dead a long time – men who fell at the Danube, men who fell at Tyre, men who fell in pointless fights in Sogdiana.

I certainly saw Black Cleitus.

And next to me, Alexander made his horse rear. He laughed, and the sound of his laughter was like a battle cry, and the sarissas came down, points glittering in the last of the sun.

Alexander turned to me and laughed again. ‘Watch this,’ he said, as he used to when we were ten and he wanted to impress me.

He put his heels to his new horse, and he was off like a boy in a race – alone. We were close to the elephants, then. He rode at them all alone. I was too stunned to follow, for a moment . . .

He put his spear under the crook of his arm, and he put that horse right through the formation of enemy elephants – in a magnificent feat of horsemanship, passing between two huge beasts who appeared from three horse lengths away to be touching. But his reckless charge was not purposeless.

Oh, no.

He left his spear an arm’s length deep in the chest of the nearest elephant, and the great thing coughed blood and reared, dropping his crew to the ground and then trampling them to death.

The whole of Porus’s line shuddered, and the king rode out again, having passed behind the elephants, and he burst out of their left flank, still all alone, and rode along the front of the hypaspitoi.

That’s when the cheers started.

He killed an elephant. In single combat.

It was like the sound a summer thunderstorm makes as it rushes across a flat plain, driven by a high wind that you have yet to feel. It started well off to the right, among the royal Hetaeroi, who now launched themselves at the rallied Indian infantry.

ALEXANDER!

The hypaspitoi had the god of war himself riding in front of them, and their shouts rose like a paean.

ALEXANDER!

The pezhetaeroi picked it up, and the Agrianians, the Toxitoi. It spread and spread, and he rode to the centre, spinning a new spear in his hand, horse perfectly under control, head bare, and those horns of blond hair protruding from his brows.

ALEXANDER!

The sunset made his pale hair flare with fire, and the blood on his arms and hands glow an inhuman red.

ALEXANDER!

I happened to be in the centre of the line, and he rode to me – a little ahead of me. He paused and looked back at me, and his eyes glowed.

‘This is it!’ he shouted to me.

At the time, I think he meant that this was the end of the battle. In retrospect, I wonder if this was what his whole life had waited for. This was it – the moment, perhaps, of apotheosis. Certainly, and I was there, the gods and the ghosts were there – the fabric of the world was rent and torn like an old temple screen when a crowd rushes the image of the god, and everything was possible at once, as Heraklitus once said.

‘ CHARGE!’ he shouted.

And we all went forward together.

The rest is hardly worth telling. I wounded Porus, and captured him – with fifty men to help me. Porus’s army broke, and ours hunted them, killing any man they caught – men who have been as terrified as ours show no mercy.

The carnage of that day was enough, by itself, to change the balance of the world.

If apotheosis came at Hydaspes, the end was near.

After the turn of the year, after Porus swore fealty (which he kept) and after the gods stopped walking the earth and went back to Olympus – after it was all over, and the slaves buried our dead – Alexander went back on his promise and marched east. We marched after the summer feasts, and we marched into more rain – rain and rain, day after day.

Victory gave us wings, for a few days. Alexander gave the troops wine, oil and cash, the takings of Porus’s camp, more women, more slaves.

Cities surrendered, and cities were sacked. We marched farther east. And three weeks later, on the banks of the Beas, the army stopped.

Amyntas son of Philip caught the king’s foot as he rode across the front of the army. The army was formed to march, but the pikes were grounded, all along the line, and the cavalry were not mounted, even though the men stood by their horses.

Amyntas pulled at the king’s foot.

The king looked down at him. ‘Speak,’ he commanded.

Amyntas didn’t grovel. He met the king’s rage with a level glance. It is hard to stare upinto a man’s eyes and keep steady. But Amyntas had faced fire and stone, ice and heat, scythed chariots, insects and elephants, and the king did not terrify him.

‘Take us home, lord,’ Amyntas begged. But in that voice you could hear not terror, but steel.