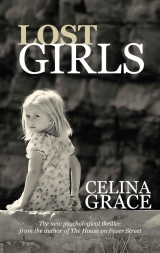

Текст книги "Lost Girls"

Автор книги: Celina Grace

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

“Yes. You’re tired now and no wonder.”

“Yes.”

I could feel the thud of his heartbeat in my ear, as it echoed through the bones of his chest. Its quick, steady pounding soothed me. I pressed myself closer to him, feeling – at last, thank God – some measure of peace. My eyes closed and when he spoke again, I had to ask him to repeat himself.

“I said, who did you think you were? I mean – did you really not realise that was you?”

“What?”

“Your reflection. You know – this afternoon–”

“Oh that.” I gave a tired giggle. “I don’t know.”

I was so tired. I could feel unconsciousness gathering itself in a slow crashing surge. My mouth seemed to move independently of my brain.

“Blonde. She was blonde.”

“Who was?”

“Jessica... Jessica was blonde.”

“Oh Maudie, darling. You’re not thinking of that again, are you?”

I wrenched my eyelids open one last time. How could I explain that I thought about her all the time, that she dogged my footsteps, that she hung about me, always that one step out of reach?

“She haunts me,” I said, my voice barely a whisper. Matt might have said something in return but by then, I was sliding into sleep.

Chapter Two

We left Caernaven early the next day. We could have stayed on, I believe Mrs. Green was expecting us to, but Matt had a seminar and a lecture the following day and he wanted to prepare. As we drove away from the house, I kept my neck rigid, unwilling to look back. Angus had always come to see us off. I could see him now in my mind’s eye, his tall spare figure on the top of the stone steps by the front door, the raising of his palm and the glint of sunlight on his wedding ring. He just wants to make sure we’re really going, Matt had once joked.

We drove without speaking. The radio played softly in the background, the sort of middle-aged, easy listening type station that Matt loved and I liked to tease him about. He had a habit of singing a line of a song very loudly, just a random line, not the chorus or anything, and not from a song that was playing on the radio or stereo, but from one that was obviously running itself in his head. It always made me jump, and then laugh, and he would look over at me in surprise. He didn’t realise he was doing it but something today was obviously stopping him as he was silent, and so was I.

I looked out of the window, watching the countryside scroll by. I thought of all the times I’d left Caernaven before, by foot, by car, by train. By ambulance.

I drew in a deep shaky breath.

“Do you remember our first meeting?” I asked, suddenly.

Matt gave me a quick, quizzical look. “Remember it? Why wouldn’t I remember it? Of course I do.”

We drove on for a moment without speaking.

“Why?” he said.

“Why what?”

“Maudie, come on. Why are you asking me that question?”

“I don’t know.” I turned my face to the window, to the banks of the motorway rolling past. “I was thinking about the past.”

“Always a dangerous thing.” He said it in a joking voice but there was an awkward undercurrent. He was right, I thought. The past can be dangerous. Or did he just mean that thinking about it was the dangerous thing? I had a sudden, ferocious urge for a drink.

“Could we stop for lunch? For a break?”

Matt shrugged. “Don’t see why not. Probably a good idea.”

“Somewhere nice. Not some dismal little service station.”

As Matt found the motorway exit and began the search for the somewhere nice I’d stipulated, I thought about Angus once more. It was usual for me, when visiting Caernaven, to take the train up. Partly it was to avoid the fag of a drive, but partly it was so I could bolster myself up on the journey with a few drinks. The trick was to pace oneself; I had to arrive fully armoured but comprehensible.

Angus normally met me at the station. Before I walked out of the entrance hall to the tiny car park beyond, I would always pause for a minute to check that the appropriate feelings were in place; mild irritation, the fretful contemplation of two days of idleness and boredom. Did other people get the same heart-sinking sensation when they went back home or was it just me? The wine I’d have drunk on the journey would numb me. There was no fear, only the vaguest tremor of anxiety that was dispelled with a shake of my head.

“How about this?” said Matt.

I came back to the present with a jerk, blinking. He was indicating a pub up ahead. It served alcohol, it was open. I tried to sound suitably grateful.

“Looks fine to me.”

When we were inside and Matt was at the bar, giving our order, I thought again of our first meeting. It had been at Caernaven, at a dinner party held by Angus. I’d come up from London, a long overdue visit; I’d stayed away deliberately, not wanting to return unless I was sure of myself. As I’d unpacked my suitcase in the bedroom, I’d looked out of the window at the familiar view – the fields and hedges spreading in a patchwork of gold and green and, far beyond, the smoky blue bulk of the mountains, the sky heaped with masses of white cloud above their peaks. Angus had sprung the dinner party on me, I remembered, and I hadn’t packed anything suitable to wear. I’d told him so at the first opportunity.

“Angus, I’ve got to go into Hellesford and get something to wear for tonight, I haven’t got anything suitable.”

He looked irritated. “Christ, Maudie, haven’t you brought anything? Why not?”

I stammered a little. “Because I – I didn’t realise–”

“You haven’t got time to go now, I need you here for six. Have you checked the spare rooms?”

“No–”

“There’s a few dresses of your mother’s still hanging about. Wear one of those.”

I felt a slight shock, as I always did when he mentioned her. She was always there but not there; not exactly censored, but rarely openly spoken of. I thought of arguing the point but gave up.

“Alright,” I said. “I’ll have a look.”

Once, I’d looked at these dresses all the time. As a small child I used to climb into the wardrobe and pull the door shut and sit there, wound about with my mother’s old clothes. I’d like to have said that they smelt of her, but of course they didn’t; they smelt of washing powder and fabric softener, not of human skin. As the years went by they smelt less pleasant, stale air beginning to permeate their fibres, until one day I closed the door of the wardrobe for the last time and left childish things behind.

There were three spare rooms on the first floor. In the second room, a bank of wardrobes stood against one wall. I flicked through the hangers, each garment wrapped in its own shroud of plastic. I found a plain black dress that looked as if it would fit. It would have to be washed and dried before I could wear it – perhaps Mrs. Green would see to it. I held it against myself for a moment, imagining my mother wearing it, sometime in the late sixties. I’d seen photos, although never of her in this actual dress. She had blonde hair like mine... I put a hand up to my head, running a strand through my fingers. I was eleven months old when she died in a car crash. I was in the car with her, but I’d escaped almost unhurt. Flying glass had cut open my face, the blood sheeting down the side of my neck like a red scarf. Otherwise, there hadn’t been another scratch on me. Like a miracle, Angus had once said to me, in an unusually unguarded moment. But I sometimes wondered whether some part of me had been hurt, as well as my face; some hidden, inner part of me. I thought that every time I saw the scar in the mirror. I shook my head. I’m better now, I told myself firmly, and marched to the door of the room.

“Penny for them?”

“What?” I said, startled. Matt was holding a glass of wine in front of my face. I tried not to grab for it.

“You were miles away.”

“I know,” I sighed. “I’m sorry.”

“Christ, darling, you don’t have to apologise. I can imagine what you’re thinking about.”

“Actually, I’m not,” I said. “I was thinking about meeting you for the first time.”

He raised his eyebrows. “Well, that’s a happy memory for a change.” He paused, then grinned. “Isn’t it?”

“Of course.”

“I even remember what you were wearing.”

“Oh yes?”

“Some lovely old dress of your mother’s. Very sexy you looked in it, too.”

I snorted. “You were wearing that bloody awful old jacket. As usual. You didn’t look sexy in it at all.”

“That must have been why I asked you on a date, and not the other way round.”

“I said yes, though.”

“Eventually.”

We regarded each other over the table, and smiled.

I hadn’t actually spoken to Matt that first night until after dinner, when everyone was out on the terrace. It was a beautiful evening, the air soft and scented with the heavy, drowsy smells of summer. Insects flickered about the outside lamps and midges came to bite us, until I went to light the citronella candles that were dotted about on the walls of the terrace. Matt saw me casting about for matches and offered me his lighter, a beautiful thing of old, polished brass, a faint design of vine leaves on its surface worn almost smooth by years of wear. He’d already lit a cigarette; I watched him smoke it slowly and thoughtfully, his eyes closing slightly on every intake of breath. I handed him back the lighter and he took it from me, his fingers brushing mine.

“I’m so pleased to meet you, Maudie,” he said, once more. “Angus talks about you a lot.”

“He does?” Momentarily, I was wrong footed. What had he been saying about me? Had he mentioned my – my illness? You’ve got to think of it as an illness, Maudie, I heard Margaret say in the confines of my head. You have to get over an illness. You have to convalesce.

I quickly put on a smile. “I hear you’re from America,” I said. “You don’t sound very American.”

He laughed. “I’m not. Just spent two years teaching over there – the University of Vermont. Do you know Vermont?”

I shook my head.

“But I’m really from here, from England,” he went on. I watched the smoke he’d inhaled seep out from between his lips and drift off in a wavering blue scarf that dissolved into the twilight. “From London. You live in London, is that right?”

“Yes, sort of Crouch End area. I have a flat there.”

“In Crouch End?” He pronounced it with the ironic French accent that every Londoner affects when they talk about the area – croooche en.

“Now I know you’re a real Londoner. They all say it like that.”

“Well, there you go. The Yanks haven’t crushed old Blighty out of me yet.”

I laughed. “You definitely don’t have an American accent, either.”

“God forbid,” he said and our eyes met. I felt an odd tremor that, for a second, made me catch my breath. I blinked and looked away.

“Anyway,” said Matt, as if I’d just spoken. “Crouch End is very nice, I hear.”

“Well, actually, it’s really more Highgate,” I said.

He looked amused. “Well, you’re doing alright for yourself, aren’t you? What do you do?”

I smiled, rather brightly. How much did he know about me? And was he just making small talk, or was he really interested? Was he patronising me? “Oh, this and that. I work at a charity. Only part-time at the moment.”

“Interesting,” said Matt.

“It’s really not,” I said, grinning. “But thanks for being polite. Want another drink?”

“Not just now,” he said, which slightly annoyed me as it meant I couldn’t go and get one for myself. “Stay and talk to me.”

“About what?”

“About – about vampires,” he said. I gave a little huff of laughter and his smile widened. “Highgate Cemetery,” he said “That’s where the vampires are, aren’t they?”

“So they say.”

He looked at me with one corner of his mouth turned up. “Not been bitten yet, have you?”

My hand went up to my throat automatically and made us both laugh.

“Not yet,” I said, and we laughed again.

*

After we’d left the pub, I fell asleep almost as soon as we rejoined the motorway. It must have been very boring for Matt, having to drive the rest of the way home with no one to talk to, but he let me sleep; I think he could see I needed it. He shook me awake gently when we were parked outside the flat.

“Wakey, wakey,” he said. “You were dead to the world. We’re home now.”

I stumbled blearily out of the car. In the lift on the way up to the flat, I looked at myself in the mirrored wall; mussed hair, pouched eyes. My scar looked very red. I shifted my gaze to Matt, who was rubbing his face, dragging a hand over the bristles of his chin.

“God, I’m bushed,” he said. “That drive never gets any easier.”

I dropped my gaze to the floor. I wondered whether he was thinking the same thing; that perhaps we wouldn’t have to do that drive anymore. Despite that, as we walked into the living room I went automatically to the phone and picked up the receiver, ready to call Angus to tell him we’d got home safely. Then I remembered and dropped the phone with a little cry and burst into tears. Matt was by my side immediately.

“Maudie–”

“I’m fine,” I said, choking. “Just – just let me be for a bit.”

“But–”

“Please.”

He stepped back warily. I lay down on the sofa and pushed my face into a cushion.

“I’ll get you a drink,” he said.

I nodded into the pillow. I couldn’t see what he was doing but I heard his footsteps move away from the sofa and into the kitchen. There was the creak of the refrigerator door and the chink of a glass bottle, the glug and trickle of liquid into a glass. Soon I heard his footsteps walking back.

“Here you go,” he said tenderly, like it was medicine. I sat up. He was holding out the brandy glass to me. I took it, rubbing the tears from my face.

“Thanks.”

He watched me drink it. Then he sat down beside me and pulled my head down onto his shoulder. I could feel his stubble catch on my hair as he rubbed his cheek against my head.

“One thing about grief,” he said. “You’ll never again feel as bad as you do right this moment. And tomorrow night, you’ll never feel quite as bad as you do tomorrow morning. And so on, and so on. That’s what they mean by time being a great healer.”

I nodded but I could have told him it wasn’t true. Time heals all wounds. It was a kind-hearted lie, a benevolent myth. Unless it took more than twenty-five years to come true.

Chapter Three

“Darling...”

I could hear Becca’s voice from across the room. I turned in my chair, watching her plough through the restaurant like a galleon in full sail.

“Darling!” Her voice went upwards as she spotted me. I grinned and waved and, two seconds later, was enveloped against her chest, the fronds of her lacy scarf muffling my face as she pressed me to her. For a moment I smelt Chanel Number Five and the sweet powdery scent of her make-up before she released me and I staggered back.

“How are you, darling? I was so worried about you, at that ghastly funeral. It’s so hard to lose a parent, it doesn’t matter how old you are. No, sit down, sit down. Have you ordered? Christ, we can’t even smoke here anymore – darling, let’s just pop out for a sec – I can have a quick smoke and you can tell me all about it – what do you say?”

As always, I felt slightly breathless. Becca has that effect on people. I always feel like throwing my hands up and saying ‘whoa, whoa’. Bless her.

“Go on, then. I can see I’m not going to get any peace until I let you have your nicotine fix.”

We took up our stations outside the entrance, huddled alongside with the other smokers who were talking and shivering and breathing out great long streams of smoke into the icy night air.

“Go on then, hon,” said Becca, inhaling with a gasp. “Are you okay? I’m so sorry I couldn’t come up to be with you, but those bastards at work would just not hear of me missing that Boston trip...”

I rolled my eyes. “Don’t worry about it, Becs. It’s fine. It’s not as though you and Angus really got on or anything, did you?”

Becca protested. “Darling, that’s a bit harsh. I only met him a couple of times. I thought we got on perfectly well, what little time we spent together. Why, did he say differently?”

I cursed myself mentally. “No, not really. You know what he was like though. Or rather, what I told you he was like. Oh, you know what I mean–”

Why had I said that? I could hear Angus’s summation of Becca clear as day in my head, after I’d taken her with me to Caernaven that one time. Too tall, too loud, too unfeminine. It was my own fault, I’d wanted to know what he thought of her. I’d wanted him to approve of her and our friendship. I should have known better. Had there been anyone in my life that Angus approved of, ever? I had a sudden unwelcome thought: if Jessica had – had lived, had been known to us as an adult, would he have approved of her?

“Becca, I’m fine. Really. I know you would have come if I’d asked you to.”

She smiled and took another lung-busting drag on her cigarette. I regarded her with affection. Darling Rebecca; henna-haired Amazon, cloaked in cigarette smoke; fond of emphatic statements; fiercely intelligent, bossy, extrovert. I’d known her five years; she was my best friend.

“Let’s go inside and order, if you’re done,” I said.

Becca gave me a strong, one-armed hug. “We need to feed you up,” she said. “Look at you, skinny-malinky. Matt’s not been taking care of you. Where is he, anyway?”

“At home. He sends his love but he had a paper to do for next week’s conference.”

“He’s going away?”

“Just down to Brighton. Some dullsville academic thing. It’s only for a few days.”

“So you’ll be all on your own? Want to come and stay with me?”

“Really, Becca,” I said, slightly annoyed. “I can cope on my own for a few days.”

“So, how are you coping?”

“What do you mean?”

“Oh, you know. Just – coping. With everything.”

We’d reached the table by now and seated ourselves.

“Becca, I’m fine, honestly. I don’t know why–“

I stopped.

“I don’t know why what?” she said.

“Oh, nothing.” I pushed my hair back from my face. I felt suddenly hot and cross. “I just don’t know why everyone’s treating me like some kind of fragile doll, all of a sudden.”

Becca reached for my hand. “You idiot,” she said, with a soft edge to her voice. “You’ve just lost your dad, that’s why. We just want to know if you’re okay.”

It was the way she said ‘your dad’ that got me. Angus had never been a dad. A father, maybe, but never a dad. I’m an orphan, I thought suddenly. The word seemed so archaic. My throat felt tight. I turned my face away for a second, getting my voice back under control.

“Thanks Becs,” I said, after a moment. “I’m fine, but thanks.”

We applied ourselves to the menus.

“Christ, I’m starving,” said Becca. “I’m going to have a starter as well.”

“Aperitif first?” I said. “Or straight onto the vino?”

“Ooh, G&T for me. And let’s get a bottle as well, to start with. The service here is always a bit hit and miss.”

I signalled to the waiter. I felt that wonderful sense of relief I always had in her presence. Becca didn’t care much what anyone thought. She just went for it, whatever it was, and it was as if I suddenly had permission to join in.

The waiter brought our drinks and we raised them to each other.

“Cheers.”

“Cheers, my lovely.”

When I got home that night, Matt was still working at his computer. The room of the study was dark, his face lit only by the bluish glow of the laptop screen.

“Still at it?” I said, surprised. “You must have been flat out all night.”

He raised his hands above his head in a ‘don’t shoot’ gesture. Then he flipped the screen of the laptop down and swung round in his chair to face me.

“I have been, truth be told. But it’s time I called it a night and this is the perfect excuse. How’s the fair Rebecca?”

“She’s fine.” I slurred a bit on the sibilant but that didn’t matter; Matt was used to me coming home tipsy from a night out with Becca.

“Did you finish your paper?”

“Just. A few footnotes to sort out and I’m done.”

“That’s good,” I said automatically. I wandered about the study, picking things up and putting them back down. It drives Matt mad when I fiddle with things, but it’s a nervous habit, I can’t seem to stop it.

“Maudie–”

“Sorry,” I said. I touched a finger to his big glass paperweight. It was like touching a bubble of solid ice. I picked it up, liking the feel of it in my palm.

“Listen,” he said, watching me. “Why don’t you come with me? To Brighton?”

“Oh, no–”

“It’ll be good for you. Change of scene and all that. You can amuse yourself during the day and come to the functions at night.”

I groaned inwardly at the thought of all those academics and their endless, impenetrable conversation, the way they all seemed middle-aged, even if they weren’t; the glasses of cheap white wine in plastic cups; the dehydrated sandwiches and sad little bowls of crisps laid out on scratched formica-topped tables. I imagined myself standing next to Matt on the periphery of each group, trying to yawn with my mouth closed.

I tried to sound regretful.

“Darling, I would but...I don’t really feel up to socialising.”

“You’ve just been to dinner with Becca. Put that thing down darling, please, and don’t fiddle.”

“That’s different,” I said, putting the paperweight back on the desk. “She’s my best friend. I don’t have to–”

“Don’t have to what?”

“Nothing,” I muttered. I picked up the paperweight again.

“No, what?”

I put the paperweight back down with a loud clack.

“I don’t need to pretend with her,” I said.

“Mind that, you’ll break it. What do you mean, pretend? You don’t have to pretend with my friends. Do you?”

I felt very tired suddenly. “It doesn’t matter, I didn’t mean it. Let’s just forget it.”

He opened his mouth and then reconsidered.

Despite my mood, I felt a spasm of drunken desire. We hadn’t made love since before the funeral. In fact, not since the day of Angus’s death, an hour after the phone call from Mrs. Green. Sex with Matt could be such an escape and that day, that was all I needed; to be as far away from reality as I could possibly be. I’d made him fuck me over and over again, until he collapsed, gasping, and said ‘no more’; until I was raw with it, a welcome physical pain to take my mind off the other, deeper kind.

But Matt didn’t make love to me that night. I lay awake beside him in the darkness of our bedroom for a long while, listening to him breathe, locked away from me in a thicket of dreams. I turned on my side and tried to empty my mind. Eventually, I did sleep, and dreamed again of Jessica, although not of the rocks and the monster. In the dream, we were riding our bikes along the harbour road in Penzance. Jessica pedalled faster and faster – she flew further away from me, as if her bike had wings. I watched her blonde hair flutter behind her as she dwindled in my vision.

I woke up suddenly. I’d been pedalling in my sleep – the covers were bunched and twisted about my legs. I had to pee and I was thirsty.

After my visit to the bathroom, I drifted to the kitchen to pour a glass of water. I didn’t turn on the light. The kitchen was lit with an orange glow from the streetlamp outside and the plane tree outside the window tossed its branches in a night breeze, the flickering shadows of its leaves moving across the kitchen counter. I shuffled into the living room and went to the window, idly twitching aside the curtain.

There was a woman standing in the street below, a tall, thin, blonde woman, dressed in a long black coat. She was staring up at the living room window. My eyes caught hers and I gasped in fright. The expression on her face was unreadable but, even at this distance, I could sense a concentration of emotion; some kind of fixed energy pulsing through her, concentrating her gaze. It occurred to me that I was still dreaming. I closed my eyes for a long moment, afraid to move. When I opened them again, she was gone. The street was empty. I felt light-headed again and clutched at my cool glass. For a mad second, I contemplated running downstairs and out into the street, to see if I could catch a glimpse of her; that blonde hair, that burning gaze, the enveloping black coat. No. I put my glass down on the windowsill and made my way back to bed. I lay under the covers, against Matt’s warm, sleeping side, my eyes wide, unwillingly awake.