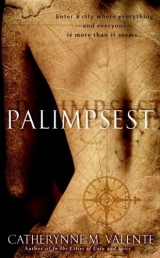

Текст книги "Palimpsest"

Автор книги: Catherynne M. Valente

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

The dead come here; the dead sleep fitful and dreaming.

If only there were a funeral tonight, then we might see such things—but there! Is that not a fine baroness shrouded in stoat fur, her fingers and toes ringed with tourmaline, tied to her golden stake and hoisted up by her weeping catamites? Is her spider-waist bound up in daisies? It is! Surely, you can see it, just there!

They will dig her grave screaming, her boys. Straight down into the earth, a pit of black and dust, in such an abandonment of grief that one or two may eat dirt until he follows her into the bathhouses of the dead. They will sink her down, standing tall and proud as she always did, as they remember her, calling for a tureen of rosemary broth and a favored one to ply his tongue beneath her gracefully uplifted gown. They will tilt her head toward the crescent moon, and as they shovel in the seedful earth around her, they will shriek, oh how they will shriek, until the owls shrink from them and hide their heads. It is possible that they will spill their seed after her in shuddering, lurching convulsions of anguish. And they will set her bamboo pole in place, small amid the great giants, and all her jewels will feed its roots.

The dead of Palimpsest are thin and tall. The process will not begin until the bamboo grave-marker reaches past the cloudline, when the vapors of the stars seep down through the impossibly long green whistle-stalk. Only then will the scalps of the deceased break the soil like babies crowning. Without noise, without opening putrescent eyes, the dead will stretch toward the scent of the stars, mute, atavistic, slow as mushrooms. Their limbs will elongate, their softened skulls compress, their hips fold in like suitcases closing, and slowly as they stretch, they will grow long and lean as their stalk of bamboo. In a thousand years the peaks of their heads may peek out of the leafy terminal end of the trees, and they may breathe the exhalations of the stars.

So they say, and so I hope.

There are some who believe that the stellar winds will blow through the ears of the dead and carry their souls back down to the city on a palanquin of light.

_______

Leonide tends the grounds here. He has a great belly, and used to joke to children that he ate the moon when there was nothing left in his cupboard. He has an enormous manicured mustache and thick hair he keeps in a bun like an old woman. His legs are those of a shaggy zebra, and he keeps them covered in stained rags and shoes made painstakingly to appear as though he still had human feet. He spades the bamboo beds and, in the honored manner of grave-keepers, long ago learned to converse with the dead. It is a happy tradition, requiring no long rituals of indoctrination or apprenticeship; the dead teach their own and in their own time.

The house of Leonide is also thin and tall. It is made of marble. He was thinking of another place when he built it, a frightening, fairy-tale world his grandmother told him about, where they bury the dead lying down, and erect marble angels over them to watch and make sure they do not reach up toward the vaporous stars. The angels are diligent there. Thus the house reaches high, but not so very far up along the length of the bamboo is stark and white, and there is an angel crouching at the door, half hidden by ferns and bougainvillea, to watch over Leonide as he comes and goes. This angel is also diligent.

Once in a very long while, during the autumn when no one can bear to die and miss the fiery trees or the coming of hoarfrost to Palimpsest, he feels himself grow forlorn and longs for conversation among the chestnut smoke and apple-heavy wind. Men are like that. It cannot be helped. On these occasions Leonide removes a pocketknife from his prodigious trousers and cuts into the side of a stalk of bamboo. He is very careful. He cuts only a small piece, a rectangle, a fortune-teller’s card, and removes it like a plaque from a high wall.

Within, a gray hand moves slightly, sluggishly. Leonide takes it in his. He holds it gently, strokes the old knuckles.

The hand squeezes back, softly, hardly a motion at all. Only a grave-keeper of the highest order would feel it, but Leonide is of such an order and such a rank, and he kisses its fingernails.

_______

Oleg places his hand upon the cool skin of a bamboo stalk. His fingers still throb, and he can feel cold, hard skin on his, though nothing touches him, and taste a red tea on his lips. He crawls with the sensation of it, with the other senses he carries with him like satchels. But they are less now, they fade. All things do, he thinks.

He looks between the trunks of this great forest; half-formed mist noses at the leaves. It is perhaps inevitable that he notices, as a locksmith must notice, the small rectangles carved into the sides of the great trees. They are so very like doors, you see. And if he finds the little doors, then he must find the long fingers, the pinched hips with sprays of birthmarks, the kneecaps like burls. And he must understand it, he must, for the dead have taught their own, in their own time, and Oleg Sadakov knows their vernacular, their diphthongs and phonemes.

“Oh,” he says. “Oh. You were here. You came here, and you saw inside the bamboo. Poor Hester—that’s why you didn’t want to come back.”

“I remember her,” comes a voice by his ear, a voice familiar and low, like hushed singing. “She screamed and screamed. And I had such things planned for her sake.”

Oleg turns, and she is there, she is there, beyond hope, she stands in her star-spangled dress, its blue train wet and sopping. Snow threads her hair. She holds a parasol that shades her sweetly, though when he looks closely at it he sees that three white foxes are sleeping on its surface, so pure and pale they seem no different from the diffident silk beneath their paws. Her face is whole and stern, Lyudmila’s face, her lips rosy and full, not burst and drowned, her eyes gently gray, her skin flushed and alive. She is warm and real and young.

Oleg feels he ought to genuflect before her as he did before the woman in the freezing streets of his waking life. But he cannot; his legs will not show her weakness.

“Where have you been?” he cries instead, and shakes her by the shoulders. The foxes stir and yawn, their pink tongues unrolling. “Why did you leave me?”

Lyudmila looks puzzled, her fine eyebrows knitting, and she puts her cold hand to his face. “I’ve been just here. I was waiting. You took so long.I was beginning to despair.”

“Well, it’s hard, Mila! It’s not exactly like hopping a train uptown. I never had to go to such lengths to see you before.”

Lyudmila purses her lips. She looks so very like their mother in that moment, her elfin face drawn in concern.

“Sometimes I worry about you, Olezhka. Really, I do.”

Oleg puts his arms around her, as needy as a young bear snuffling for friendly paws in the wintry dark. She allows herself to be held, even lifted slightly off her feet; she pets his head tenderly. Her weight is real and solid in his grasp—she is so alive, and her skin beneath his palms is hot.

“I missed you, Mila. I missed you so.”

“You were not relieved to have an apartment to yourself? To let your tea go cold if you pleased, to kiss pretty things on your couch without dark eyes burning behind the curtains?”

“No.” Oleg shakes his head fiercely. “No, never.”

“Well.” Lyudmila disentangles herself, smoothing her skirt with a blue-gloved hand. “Well, then. That’s settled.” She catches his wrist suddenly, sharply, her even nails cutting into him, her grip bony and rigid. “Don’t make me wait again,” she hisses, and looses him as suddenly, as sharply.

She leads him away through the forest, and he can hear, as if from far away, winds whistling through the stalks: it is almost a song they make together, but it cannot hold, and falls into scattering storm-whirls before the first verse is done.

_______

There is a small boat tied with a length of leather to a tarnished silver pier. It is not Gabriel’s gondola, but it sweeps in slender fashion from end to end in same general manner, and there are garlands on it, of seaweed and of marigolds. Lyudmila holds out her hand, intending in some genteel forgotten way to communicate that he ought to help her aboard, and Oleg hurries to her.

The river is milky and thick as before, the cream in it a long golden ribbon. Lyudmila sits primly at the head of their craft and it drifts tranquilly downstream. She neither steers nor rows, but they keep their course. She gives him a smile like a present wrapped in red.

“I will take you anywhere you wish to go,” she says brightly.

Oleg touches her foot with his foot. Her color is high in the honey-sweet wind, he has never seen her like this. She is beautiful,he realizes, she grew up to be beautiful.

“Take me to a place where you and I may lie on a long bed with our knees tucked together. Take me to a place where I can make smoky tea that you will love to drink, where lemons grow and also where plovers sing at dusk. Take me to a place with a little mirror where I can shave, and a basin full of water where you can wash your hair. I could be happy in a place like that, I think. I could watch you sleep there. I could boil eggs for us, and bake bread for you.”

“You want so little.”

“Not so little.”

They pass an hour in silence. The parasol-foxes chew at fleas and snap at passing mayflies, the jeweled bodies crunching between their vulpine teeth. Palimpsest yawns enormous on one side of the river, towers and leviathan flying buttresses ablaze with hanging lanterns, falcons screeching down the long canyons between them. On the other side, small towns stretch lazily along the greening mud, the clotted river thickening in the shallows, the polished logs of underwater nets floating sleepily on the yellowish currents.

“Look to the banks, Olezhka,” Lyudmila says finally. “And the moon falling there, on the spires and houses.” The knotted white buildings sleeping on the right-hand bank are warped like gnarled bones, many of them half-crushed, their dust feeding the river. There is a cathedral of a sort, and on its roof a lonely monk blows a long black trumpet. The moonlight is brighter than day there, and only there. The river remains in shadow. Men and women crawl out of the ruined houses and hold great glass jam jars above their heads, their long hair spilling back to the earth. The moonlight pours into the jars; the women screw on brass lids with muscled arms, piling their shelves with them, jar upon jar.

“There was a war once,” Mila murmurs. “It began here. In this very spot. It was not a very long time ago.”

“How can there be war in this place?”

Lyudmila shrugs, her eyes downcast. “War likes best those towns that have grass growing on their roofs and apples on their trees, and especially those with industrious women who have lovers with strong brown backs. This was a town like that on the shores of the Albumen River, whose yolk was once rich and young. Before Casimira and her chariots, before the fires, before the moths with their awful wings and poisons. The cider was so fierce here it would take you off your feet in a swallow.”

“Who is Casimira? What happened? How did it end?”

But Lyudmila’s face is shadowed, as if she grapples with some private grief he cannot touch. Instead, like a good brother and a dear one, he lays his head in her lap and wraps his arms around her knees. The boat wavers, but rights itself and passes the mournful town in utter silence. The last jar is screwed tight, and the moon goes out. It is very dark on the river now, and the stars shiver. Lyudmila smoothes his hair absently.

“In the land of the dead,” she says finally, her voice clear and cold across the water, “a boy who died of a fever wished to make his fortune in the munitions factories of that unfortunate land. And so he went to the districts of those who had died in battle, and begged from each of them the bullets that had pierced them, which they each carried in their tin lunchboxes. There was one girl only who would not give over her bullet—”

“Lyudmila,” Oleg interrupts softly, “why don’t you drip water from your mouth when you speak anymore?”

She is quiet; her hand freezes on his temple.

“Do not ask me that, Olezhka. Let it be just a little while longer.”

“All right, Mila.”

Clouds sweep over the stars, and there is no light left on the long, white river.

FOUR

PEREGRINATIONS

Nerezza cradled Ludovico’s head in her arms. She did it awkwardly, not being by nature a nurturing dove of any breed, unused to ailing men in her bed, in her kitchen, in need of her coffee grinder’s shrill whirring and her boiling water, in need of her. But she tried, gamely, as another woman might try to swallow fiery spices out of politeness.

“Ludo, drink. You have to.”

He turned his head from her, for a moment thinking he might throw up.

“Lucia,” he groaned.

Nerezza rolled her eyes. “Yes, Lucia. I know. It doesn’t mean you don’t need to drink when I tell you to.”

Ludo drank. It was bitter and thick and duskily sweet. Lucia had often ordered him about—he required it, flourished under it, as he could never remember that eating remained vital even when a book was overdue and so beautiful it cracked his sternum with the force of it. She had had to curl his fingers around a spoon once, when a new American translation of the Bucolicswas on the press and unconscionably late. Ludo had not tasted the carroty soup or the bread, but she had tasted for both of them.

“If you cry in my house,” Nerezza said, “I shall call security.”

“I don’t understand.” Ludo opened his eyes to a room flooded with sunlight, all the brighter for her sparse belongings. The sunlight seemed to be unsure of what to do in the absence of a couch to fade or curtains to shine through, and so had gone helplessly nova in the center of Nerezza’s living room. He groaned again, his head throbbing like a struck bell.

“Don’t you? I know it’s hard to keep in your head, a hard wrestle, like Jacob and that angel. But she’s there, you must see that. You saw her. She’s there and safe and you don’t have to worry about her anymore.”

“Where the fuck is there?” Ludo did not often swear, but he felt he had placed the word perfectly, squarely.

Nerezza looked at her shoes. She was dressed already, in cream and camel, impeccable, and Ludo thought she probably didn’t know how to be anything less than that.

“Palimpsest,” she whispered. “Don’t make me . . . I don’t like saying it. Here. I don’t like saying it here.”

Ludovico extricated himself clumsily from her and stalked into the small kitchen, buttering bread and slicing cheese for himself without speaking to her. He could feel her watching him fumble with her knives, knew his cheeks blazed with little points of blush that could not quite spread.

Nerezza folded and unfolded her hands. “I know—”

“I am not discussing this,” he snapped.

“You were there, Ludo! You saw the horses. You ate a snail with a silver shell. You saw her, you saw Paola—that’s her lover’s name, Paola. Did you know her?” Nerezza hurried on. “You sat next to me and I tasted your tears.”

“I had a bad fucking dream.” He felt satisfied having used that word again, as though it were a badge he could wear and polish.

“Dreams don’t work like that. Two people don’t dream identical dreams.”

“I am not discussing it.”

Nerezza shrugged. “It’s not that I feel responsible for you. I feel . . .” She stared at the precise moons of her cuticles. Strands of dark hair had begun to work loose from the meticulously messy knot at the nape of her neck. “I feel that Lucia left her life untidy, and as her friend it is my duty to order it. If not for her, I would never have seen the things I’ve seen. It is the least I can do to . . .” She looked sidelong at him through her lashes. Ludo could not tell whether she meant the expression to look kittenish or morbid. “Feed her animals while she’s gone.”

Ludo gripped the edges of the cream-colored countertop. He shut his eyes; the sunlight turned his eyelids to a ruby smear. Had she been here? Had she eaten this brown bread with crystals of coppery sugar in the crust? Had she let a cigarette sigh into ash on that light-scoured terrace? He tasted the snail still on his lips; there were such screams in his ears, ringing, ringing! But it was a mad thing, an impossible thing. Leave it to Lucia to find a madness so big she could vanish into it and drag him with her, far behind, weeping for her, like a penitent on a chain, stumbling behind the priest’s cart.

“If you want to see her again,” Nerezza said quietly, “you have to accept this. It’s fairly simple, in the end.”

“If she wanted to leave me, there might have been a divorce. I’ve always liked legal documents. They feel so real. That would have been easier. Quicker. More final.”

“This is very final. Or will be, when she’s finished.”

“You don’t know her. You don’t know us. She will find a way back to me, if the world is as you say and all this is real.”

Nerezza laughed, a bark, a snap of an eel’s electric tail. “She’s gone, Ludo. And if she’s lucky, she’ll soon be in Palimpsest forever, and you’ll only see her if you fuck the right shopgirl.”

“But she’s not there yet? Not completely? She’s somewhere here, too, in Italy, in Europe? America?”

Nerezza threw up her hands in disgust. “Oh, for Christ’s sake. No onehas gotten there yet, completely, permanently. But yes. I drove her to the airport. So that she could try. I helped her get a passport. You have no idea what she and I have been through together—I was there, I watched her go, toward Paola and Palimpsest and all of it. I helped her. She would have bled through her eyes for it. So would I. God,” she raised her eyes to the impassive ceiling, “if only the toll were as cheaply paid as that. If only I could bleed and that would be enough.”

Helpless in the face of his idiocy, she lifted her slim shoulders and let them fall. He tired her, he could see it. An animal who made a mess all over her house. His tears and his semen on her sheets, the endless laundry of him, the endless water he required and gave back uglier, saltier, than he had received it.

A small knock came at the door, like a polite cough. Nerezza’s face did a curious thing; it flushed, and she smiled, a smile which seemed to come out of her marrow, raw and livid. Her dark eyes dazzled and Ludo quailed from her a little, from this woman, the mark of whose mouth still blazed on his cheek.

A man and a woman stood at the door, clutching each other’s hands fiercely. Nerezza took them both in her arms and the three of them stood for a moment, their heads pressed together, their arms hanging limp around each other’s waists. Ludo bit his lip, bearing within him the awful feeling of stalking in the cold just outside the warm glow of a fire, unable to draw closer. The man kissed the top of Nerezza’s head with a rough tenderness; the woman laid her head in the crook of her shoulder. When they finally broke ranks, Nerezza led them both by the hand to the kitchen, where Ludo shrank against the wall, trying not to appear as though he shrank at all. They were strangers, their eyes full of tears, and they advanced on him like assassins. He longed to flee.

“I asked them to come, Ludo,” Nerezza said. Her voice was rough and harsh, an eel-voice, from the deeps, and he found in that moment that he hated it. “So that we could explain to you, so that they could. It’s a hard progress we make, and lonely, frightening—but it doesn’t have to be like that. This is Anoud, and this is Agostino. They are my lovers.” She paused for a moment, as if to make space for Ludo’s disapproval to have its little fit. “But that’s not why they’re here.” The two of them nodded eagerly. Anoud was dark, Moroccan maybe, her skin the color of old dust. Agostino was tall and ascetic, with an ungainly nose and a distantly grieving expression. He looked to Ludo like a man who wept often. The trio guided him to the long chaises of Nerezza’s minimal living room, and he allowed himself to be seated, his limbs arranged like a doll’s. They stared at each other for a long time, unwilling to be the first to speak, but Anoud and Agostino did not let go of Nerezza’s hands, clutching them so tightly that the tips of her thumbs had gone purple. Nerezza began, her voice soft, buoyed by her lovers’ presence.

“Do you remember, Ludovico, the first night? Do you remember the house with the frog-woman in it?”

He did not want to admit to this. It was like admitting to syringes in the refrigerator or being unable to read. He did not like to be pried open at the hinges and stared into, murmured about in disapproving tones. Why couldn’t Lucia just stay with him, in their little home, with their books and their roasted chickens? Why must this horrid scene now play out?

“Yes,” he said gruffly, biting the word in two.

“Her name is Orlande,” said Agostino. His words echoed loudly, too loud in this place.

“Do you remember that you were not alone?” asked Anoud sweetly, looking tenderly at Nerezza, and a flood of jealousy released bile into Ludo’s heart.

“You must think very hard, Ludo,” said Nerezza. “You must try to remember. There were others, with you. Then, and now. When you sat in the stands with me, you felt them, you felt someone else eating when you had no plate before you. Someone else kissing when you were not.”

He struggled—it is never easy to remember a dream. A fleeting vision of long, blue hair swept through him, and he shuddered with it. St. Isidore, you never imagined this thing,Ludo implored silently. In what column would you have placed it?

“There were three of them,” Ludo said slowly, and he felt the weight of that memory lift from him. “One had blue hair. She was very young. Another, I think, another had a bee sting on her face. And there was a man with keys hanging from his belt.”

“Yes,” breathed Nerezza. “Anoud and Agostino, you understand, were there when I sat in Orlande’s shop, when I put my feet into the ink.”

“Only two?”

Nerezza pressed her lips together until they went white, and her companions would not look at him. They seemed to sag into each other, their breath stolen.

“About three years ago,” Nerezza said, “our friend Radoslav was killed. He was the other one, in Orlande’s shop with us. It’s . . . so hard to stay careful there. It is easy to become involved in unsavory things, and easier still to find oneself without shelter in dark alleys. There are people in Palimpsest—they call themselves Dvorniki . . . it means ‘street-cleaners.’ They’re veterans, you remember? Like I showed you, at the races. Their leader, or priestess, or whatever, has a shark’s head. They hold sabbats in doorways, any doorway, but they have a great, huge one built in the basement of the big train station . . . you haven’t been there yet, though. Anyway, it’s just an empty, carved doorframe, all black. No door, no hinge. And they . . . well, it’s wonderful there, in Palimpsest, but sometimes it’s not very nice.”

Anoud took up when Nerezza’s voice faltered—Ludo did not even know such a thing could happen! “Radoslav cheated a Dvornik at Valorous,”she continued. “That’s a game, with little copper stars you move around a board covered in white silk. He couldn’t have known the man was political. Radya was just . . . like that. Reckless. They came for him while he was drinking licorice wine in a hotel—the most civilized thing you can imagine, and the Dvorniki just grabbed him, with crab claws and donkey jaws. . . . They dragged him to the train station, to that big black doorframe, and they cut his throat on the lintel, praying that no immigrants should ever find their way to Palimpsest, that his blood would seal all the ways and roads.”

“It’s so stupid.” Agostino sighed. “Brutal, idiotic, Neolithic rituals, and they don’t work anyway. If they worked there would never have been a war.”

Ludo shook his head. “I’m sorry he died, but—”

“You don’t understand,” Nerezza snapped, her eel-tail back, her blue sparks crackling. “We wrote letters to him. We talked on the phone, for hours and hours. We had found him working in a provincial post office in Isaszey, in Hungary, of all absurd places. We had planned to meet that summer, we had rooms at the Sofitel in Budapest, we had planned it like a picnic. We needed time, you see, time to tidy things. And to delay the pleasure of it was natural to us.”

Again, Nerezza lifted her shoulders—not a shrug, but her only gesture of helplessness, of submission to the constellations and the turning of invisible clocks. The grief on their faces was so naked that Ludo turned away from it with the same propriety he would have shown to a girl caught undressing.

“But didn’t he just wake up? I mean, if it happened there, shouldn’t he be all right here? Isn’t that how it works?”

Anoud began to cry softly, little wrinkled noises he could hardly hear. Agostino caressed her face with two curled fingers. Nerezza stared stonily at him and shook her head.

“Do you remember how often Lucia traveled out of Italy before she disappeared?” Nerezza continued, abandoning his question. She did not weep, even a little.

No, of course he didn’t remember. Lucia left; she came home. He did not try to track her, what would be the use, with that great tail, that determined erasure? Where had she gotten the money for such things? Impossible that this could have occurred while he looked the other way, that Lucia could have been so consumed by something not him. He wanted Nerezza to stop talking, to just shut upand leave him alone.

“She was looking for her . . . Quarto. That’s what it’s called. What immigrantscall it.”

Anoud laughed through her tears, a squeaky, mouselike sound. “That’s us,” she said. “Immigrants. Saying these words is always so hard! They sound so ridiculous in the daylight, with coffee in the pot and cats crying to be let in. They sound poor and small. But we did know her, Ludovico. We all did. There are not so many of us that we do not find ways to know each other. She was looking for them, and she found two of them. Their names are Alastair and Paola. We never met them. Paola was Canadian; that’s so far away.”

“But Hal,” Agostino cut in, his gangly arms still draped around both women, “Hal lives in—” Nerezza shushed him, and he hurried on without naming a city. Ludo wanted to throttle him. “Well, he wasn’t so far. They met just a little while ago. They found each other, like we did. And they went to find the others together. We think . . . we think that’s how it’s done. How you get to Palimpsest permanently. How you . . . emigrate. We think you have to find your Quarto here, in this world.”

Ludo felt his blood beat against his face. The great unsaid thing floated heavy and choleric in the room. “Am I correct,” he said, “in assuming that there is no one in this room who has not slept with my wife?”

He had been prepared for silence and took it for his answer. Ludo was, he knew, deep in the book of beasts, crushed between their many pages, growling all around. Anoud slid out of the grasp of her lovers’ hands and alighted by him. She had a pinched nose, small eyes—an ungenerous face, he thought. A mouse, certainly, if ever a woman had been a mouse. Hay-child, impossible generation, and such plagues. He was distracted by her hands, so slender he could not imagine there was flesh between skin and bone, and on her smallest finger was a carnelian ring, a smear of red on gold, the tiniest of stones.

Ludo had bought it in Ostia that long-ago summer, the summer of the yellow dress, when he and Lucia sought out that wonderful pecan-red shade on everything: rings, couches. When they bought wildly things to build a house around them, certain that nothing they laid their hands on would ever need altering, replacing.

Ludovico reached for Anoud’s hand and she gave it warmly, stroking his cheek with the other, a kind attention, as if soothing a child whose knee has been skinned. But he did not want her hand. He tugged at the little ring; it would not come. Anoud tried to draw her hand away, but he seized her wrist and scrabbled at the ring with his fingernails. His tears came as quickly as her little well of blood beneath the band, and between their fluids he wrested it from her, his breath hitching with panicked cries. Anoud held her finger to her lips and glared at him, wounded, bereft. Her gaze flickered to Nerezza and back to him. She inched closer, carefully, a little mouse seeking the owl’s audience, with one round ear lost already. She held her scratched hand to his mouth; he knew this gesture, as every Catholic child knows it, and he kissed the signet of her blood.

“I’m sorry,” Anoud whispered. “I loved her, if that matters. It’s easy for me to fall in love. You could say I’m a prodigy. I loved her, and I can love you. I can see a day not so very far distant when you bring me tea before dawn and kiss the hair from my forehead. My capacities are not less than hers.”

She kissed him truly, her tongue small and hesitant, her curly hair brushing his cheeks. She tasted strange, foreign in his mouth, like a red spice. Ludovico’s bones groaned in him. She was sweeter and smaller than Nerezza. Softer. More tamed, gentler, eager to be loved.

“Don’t you want to seeit?” Anoud breathed. “Just see the races and the feasts and the ocean? Just taste the air? Don’t you remember how sweet the wind is there? Does the city hold nothing you desire?”

Ludovico did remember, after all. Not just Lucia. He remembered the snail-seller, and the sea wind. Fine, he thought. I give in. I give in to this, if that is what is asked. If I must pay in women for the city, for all it contains. I can bend under it as under God. As I bent under Lucia, my star of the sea, my endless storm.

And so Ludo returned Anoud’s kiss. He pulled her white shirt from dark shoulders and pressed his face to her breasts, fuller than Lucia’s, with nipples like coffee beans. He cried out into her skin and she accepted his cry with a merciful quiet, letting his cry fall all the way down to her heart. She guided him onto her, moved Nerezza’s spare bathrobe aside to bring him into her, arching her back to show him the hidden smallnesses of her mouse-body, pressing her knees to his hips. Ludovico looked past her as he rocked back and forth with her motion, providing little of his own. She was so slight he hardly felt her beneath him, just the wet warmth of her around him, clutching gently. Ludo was silent, aghast in his submission, the little ring still clutched tight in his fist. He looked to Nerezza—shameless thing!—her head thrown back in Agostino’s arms as he thrust his angular body into her over and over, his braying bull-voice muffled in her neck. Her mouth was open, her face streaked with tears.