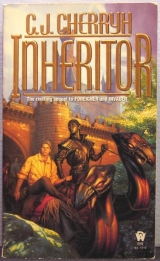

Текст книги "Inheritor"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Delusion played a large part in Mospheiran attitudes.

Delusion that they had a spacecraft, or could build one, with no facility in which to do it.

Delusion that they could fix their deficits when there was suddenly a great need and all their bets came due.

Self-delusion to which, apparently, he was not immune.

“Lifestyle,” he said, with self-knowledge a bitter lump in his chest. “But I still do plan to go fishing, Jase.”

“Just not this trip.”

“Even this trip, dammit! Security alerts go on all the time. I livewith it! In between times, I relax, if I can get a few hours. Nine tenths of the time nothing happens or it happens elsewhere and life goes on. If you’ve planned a fishing trip, it might be possible. We can rent the gear. And hire a boat.”

“It’s a nervous way to live.”

“It is when you park a bloody huge ship over our heads and offer the sun, the moon, and the stars to whoever gets there first! It makes the whole world a little anxious, Jase!”

“Was life more peaceful before we came?”

“Life was absolutely ordinary before you came. You’ve set the whole world on its ear. Don’t you reckon that? Absolutely ordinary people’s lives have been totally disrupted. Absolutely ordinary people have done things they’d never have done.”

“Good or bad?”

“Maybe both.”

They rode a while more in silence. He watched Jago ahead of him, by no means ordinary, neither she nor Banichi.

He lovedJago. He loved both of them.

“A lotof both,” he said.

And a long while later he asked, “ Whydid the ship come back?”

“Weren’t we supposed to?”

He thought about that a moment, thought about it and wondered about it and said to himself of course that was what the ship did and was supposed to do: go places between stars. And this was where other humans were, and why wouldn’t it come here?

But he always argued the other point of view—everyone’s point of view: Barb’s, his mother’s, Jase’s. He’d elaborated in his own mind Jase’s half-given answers in the days when Jase hadn’t been able to say much in Ragi and after that when the pressure mounted to get the engineering translation settled. They’d talked fluently about seals and heat shields. But when he’d asked, in Mosphei’, as late as a handful of days before his tour, Where were you? Jase had drawn him diagrams that didn’t make any sense to him.

And he’d said to himself, when he hadn’t understood Jase’s answer or gotten any satisfaction out of it, well, he wasn’t an astronomer and he didn’t understand the ship’s navigation; or maybe space wasn’t as romantic as he’d thought it was—or maybe—or maybe—or maybe.

Well, but. But. But.

Did delusion play a part in it? Or a human urge to fill out Jase’s participation and make excuses for behavior that otherwise wasn’t satisfying his expectations.

The ship was doing as it promised. The spacecraft was becoming a reality.

But in his failure to find the friendly, cheerful young man he’d talked to by radio link before the drop, he’d insisted on making that side of Jase exist in the apartment.

He’d done all Jase’s side of the conversations in his head, was what he’d done. He’d made up all sorts of answerless answers Jase mightgive, if Jase had the vocabulary, if he had time to sit and talk at depth. Naturally Jase was under stress: language learning did that to a mind. Or maybe—or maybe Jase had been doing the same, filling in between the lines to suit hisinitial impression; and when those expectations didn’t match reality, he felt betrayed.

“Jase,” he said.

“What?”

“Where wasthe ship?”

“I told you. A star. A number on a chart.”

“You know the feeling you had we weren’t going fishing?”

“Yes?”

“It’s what I feel when you tell me that.”

Silence followed. It wasn’t a happy silence. He wished at leisure he hadn’t come at Jase with that.

He wished a miracle would happen and Jase would come out of his sulk and be the person he’d thought he was getting, the person who’d help him, not pose him problems; the person who’d stand by him with reason when the going got tough.

But Barb had done that until she’d had enough. She’d run to marry Paul Saarinson. Maybe Jase didn’t want a career of keeping the paidhi mentally together, considering they had to share an apartment.

Maybe in meeting him, the astonishing thought came to him, Jase hadn’t found the man he’dthought he was dealing with, either. The breakdown of trust might be rooted more deeply than any dispute over truthfulness, in failings of his own. He managed so wellwith atevi. His personal life—

Ask Barb how he got along. Ask Barb how easy it was to deal with him.

He remembered Wilson-paidhi. He remembered saying to himself he wouldn’t ever get to that state. The bet had been among University students in the program that Wilson couldn’t smile. That Wilson couldn’treact. Grim man. Unresponsive as hell.

But at the same time those of them going for the single Field Service slot learned to contain what they felt. You learned not to show it. You studiedbeing unreadable.

Barb had complained of it. Barb used to say—he could remember her face across that candlelit table—You’re not on the mainland, Bren. It’s me, Bren.

It gave him a queasy feeling to realize, well, maybe– maybeit had something to do with the falling away and the anger of humans he dealt with. But he’d told Jase. He’d tried to teach Jase to do it. Jase should realize why he didn’t show expression.

Shouldn’the realize it?

Move that into the category of fishing trips.

Fact was, he’d told Jase notto show emotion with atevi, and when Banichi and Jago walked in, he’d been laughing and lively and all those things he’d taught Jase not to be.

Maybe they should have thought a little less about language early on, and more about communication. Maybe they should have learned first what they expected of each other instead of each resigning himself to what he’d gotten.

“You and I,” he said in Mosphei’, “you and I need to talk, Jase. We need it very badly.”

“We were going to do that out here.”

“I’m sorry.I didn’t remotely know what I was getting you into. I knew it was a chancy time. It’s alwaysa chancy time, especially when the pressure mounts up and you want to get away. I knew present company was the chanciest thing on the planet but the people who can doanything always are. It’s the way it works, Jase.”

“I trust you,” Jase said in a curiously fragile tone—had to say it loudly, with all the thump and creak of the mechieti. “I do trustyou, Bren. I’m trying like hell to.”

“I’ll get you back in one piece,” he said. “I swear I will.”

“That isn’t what I’m worried about.”

“What is?” he asked, thinking he’d finally gotten one thread that might pull up a clue to Jase’s thinking.

But Jase didn’t answer that.

And in the next moment he saw Cenedi rein back while Babs kept going. Something was going on. He thought Cenedi had done that to talk to Banichi.

But he was the target. Cenedi fell all the way back to him and Jase.

“Bren-paidhi,” Cenedi said, as Bren restrained Nokhada from a nip at her rival. “The dowager asks why you avoid her. She told me to say exactly that, and to say that Nokhada still knows her way, nadi, if you’ve forgotten.”

22

Nokhada indeed knew the way, and with a little laxness on his part thought she was being sly about moving forward. Had he touched her with the crop, he’d have been there at the expense of every mechieta in front of her.

As it was, Nokhada announced to the mechieti in her path she was coming through with small butts of her head, a little push with the rooting-tusks against an obstinate flank. Mechieti hide was fortunately thick, and tails lashed and heads tossed, but no blood resulted, just ruffling of well-groomed hair.

Cenedi had lagged back. Nokhada achieved the position she wanted, next to Babsidi, and became quite tractable.

“Ah, well,” Ilisidi said, sitting with that easy, graceful seat. She deigned a sidelong glance. “One can only imagine.”

One didn’t dare say a thing.

“Oh, come, come, nand’ paidhi. Arewe like humans? Or are humans like us? Is it—how am I to put it delicately—technically feasible?”

“One is certain we are not the first pair to have made the—” That led, in Ragi, to a difficult grammatical pass. He was sure he blushed. “To try.”

“Was it pleasant?” she asked, delighting, damn her, to ask.

“Yes, nand’ dowager.” He wouldn’t retreat, and met her sidelong glance with a pleasant smile.

Her grin could blind the sun. And vanished, in pursed lips. “Now that the world knows the paidhi has such interests, there’ll be suchgossip. My neighbor who loves to spy on my balcony will be absolutely convincedof scandal in our little breakfasts, now. We must do it again.”

“I would be delighted, aiji-ma.” He had no need to feign relief to have her take it well. “I treasure those hours you give to me.”

“Oh, not that I have any scarcity of hours! I languish in disuse. My hours are such a little gift.”

“Your hours and your good sense are my rescue, aiji-ma, and so I trespass egregiously on them, but never, never wish to impose.”

“Languishing, I say. And now, now you drop young men from the heavens and expect meto civilize them.—Did I detect strife, nand’ paidhi? Do I find discord?”

“He doesn’t expect fish at this altitude.”

Ilisidi laughed and laughed.

“Ah, paidhi-ji, a fish is what we hope for. A great gape-mouthed fish of a Kadigidi, which thinks to wreck us. I wanted you with me, Bren-ji. I likethe numbers we’ve worked with this far; and I nevertempt an Atageini beyond his virtue.”

He was shocked. Outright shocked. Banichi and Jago had ridden up on his right and he wondered if theyhad accounted how great a temptation the paidhiin posed inside an Atageini perimeter, with the dice in motion, the demons of chance and fortune given their moment to overthrow the order of the world.

Baji-naji. The latticework of the universe, that allowed movement in the design.

Tabini was sleeping with the Atageini: Tatiseigi had made his move to get into the apartment to get at them, for good or ill or just to make up his mind, and Ilisidi had moved in. Ilisidi had possessed herself of the greatest temptation that might tip the Atageini toward a power-grab of their own, just flicked temptation out of Tatiseigi’s reach at the very moment it might prove critical to his choice of direction in these few dangerous days.

Believe that Tabini didn’t see it? Possible. Remotely possible.

But ifTabini should miscalculate, if he should wake up stabbed by an Atageini bride, the Atageini and the Kadigidi alike had to reckon that getting rid of Tabini didn’t kill Ilisidi.

And twicethe Padi Valley nobles had politicked to keep Ilisidi from being aiji.

Dare Tatiseigi move on Tabini now, or move on Ilisidi, who had the paidhiin in the middle of an action that could put them all, if it failed, in Kadigidi hands?

Tabini’s rule was a two-headed beast. He saw that now with crystal clarity.

Bane of my life, Tabini called Ilisidi.

And Tabini had resorted to her in what seemed reckless action when he knew he had to contemplate war with Mospheira.

She hadn’t gone home since.

“Any news?” she asked Cenedi now.

“Quiet still, aiji-ma.”

“Well, well, so long as it lasts.”

The dowager called rest, and Bren actively rodeNokhada back through the company as it drew to a halt, a choice he was sure, in the way he’d come to understand how Nokhada did think, that Nokhada perfectly well understood. She expressed her dislike with flattened ears and a bone-jarring gait which he had come to understand he had to answer with a swat or she’d think her rider wasn’t listening.

But not with the heel, or he’d be through the company like a shot: he used the crop at the same time he kept a pressure on the rein. The gust of breath and the shift into a smooth gait was immediate as she moved through mechieti establishing rights over their small patches of green grass, a touchy business of snarls and status in the herd; and Nokhada breezed past lower-status mechieti with scarcely a missed beat, back to where Jase and the boy were already dismounted.

He stopped Nokhada at the edge of the herd and slid down, keeping the rein in hand and the crop visible, against what otherwise might be a tendency slyly to wander closer to Babsidi during the stop.

The head went down; she snatched mouthfuls of grass.

Jase didn’t ask him, What did the dowager want? The boy didn’t, either. But the boy wasn’t his partner.

Maybe, the amazing thought dawned on him, Jase was waiting for hisally to say something.

And, dammit, the boy was underfoot and all ears, he was sure. He couldn’t send the boy to Banichi. They were talking to Cenedi on matters the boy didn’t need to hear, either. He looked in that direction and met the boy’s absolutely earnest gaze.

And saw the escort. “Nadi,” he said to the man, “Haduni, please brief the young gentleman: we may have to take a faster pace.”

“Nand’ paidhi.” Haduni gave a nod as if he perfectly understood and had been waiting for such an order, then smoothly collected the all-elbows young lord and steered him to the side.

Bren heaved a sigh and with a sharp jerk of two fingers against the rein in his left hand, checked Nokhada’s intent to gain a few meters on her agenda. “He’s very anxious,” he said to Jase. “He sees the reputation of his house at stake.”

“What did they want up there?” Jase obligingly asked the question. Jase did the obvious next step.

“To be sure I knew things were all right,” he said and told himself to relax, let his face relax, useexpression.

And what in hell was he supposed to do? Grin like a fool? He looked at the grass under his feet and looked up and managed a little smile, one he trusted didn’t look foolish. When he knew damned well he hadn’t been shut down with Ilisidi. He just let Jase touch off his defenses, thatwas what he was doing, and it was a flywheel effect of distrust and guardedness.

“Jase, she said Tatiseigi might– might—have moved against us. I’d hope he wouldn’t, but she said his virtue was a lot safer if we weren’t in his reach. I didn’t think that. But I did think things in Shejidan were going to go a lot more smoothly without us in the way. So it was the same move, two reasons.”

Jase was listening, at least, without the anger he’d shown.

“We aregoing to Mogari-nai, nadi?” Jase switched back to Ragi.

“I have no doubt of it. The Messengers’ Guild has been pulling at the rein—” Source of his metaphor, Nokhada tried a different vector and got another jerk of the rein he held, hands behind his back. “And Ilisidi intends to make it clear the authority is in Shejidan, not in the regional capitals. That’s an old issue, the amount of power Shejidan holds, the amount of power the regions have. They’ve fought over it before. Your ship dumping technology into Tabini’s hands has raised the issue again. That’s whythe tension between some of the lords and the capital.”

There followed one of those small, tense silences, Jase looking straight at him as if thoughts alone could bridge the gap.

“Thank you,” Jase said then, carefully controlled. “ Thankyou, nadi.”

“Why?” was the invited question. He asked it, angry in advance.

“It’s the first time,” Jase said, “that I’ve ever felt I’ve heard the truth.”

“I have not—”—lied, he almost said. But of course he had. And would. “I haven’t known what I couldsay.” He changed back to Mosphei’ to be absolutely certain that Jase understood him. “Jase, if I told your ship enough to let them think they could guess the rest and go hellbent ahead, I knewthey could tear the peace apart. You can seenow what the stresses in the atevi system are, and I don’t know the quality of people in office on your ship. But the people in my government who’ve cut the Mospheiran Foreign Office off from communication with the Mospheiran public have completely written off the majority of people on this planet as of no value to them. They’re not pleased with my continuing to operate as theForeign Office, such as it is, but here I am, and here I stay. That, I havetold you. For what you can see with your own eyes, look around you. See how it works. Seethe land. See the people. See everything you came here to see. It’s all I’ve got to offer you.”

And even while he said it he was hedging his bets, telling himself—just get that spacecraft built, get it flying, get atevi up there before politics shuts atevi out of the meaningful decisions.

If he could get help—he’d take it.

But jeopardize that objective? No.

Jase didn’t answer him. He decided that was a relief. He couldn’t debate trust with Jase. It didn’t exist. It might, eventually, but it didn’t, not here, not now. He daren’t debate it with Ilisidi, either, but he did trust her, as far as he could reason what she was doing.

Banichi and Jago—there was his one known quantity, though Tabini never was: believe that those two, who were right now deep in conversation with Cenedi, would bend Tabini’s orders a little to save his neck. He was sure they had done that very significantly at least once. Believe that Tabini valued him andhis objectives? So far he was irreplaceable.

One of Ilisidi’s men came close to him, Haduni, bringing the boy back. He looked in that direction and saw them offloading the baggage from the mechieti.

Are we camping here? he wondered. That didn’t accord with his knowledge of the situation.

No, he thought, seeing men adjusting mechieti harness, we’re going to move.

Harness adjustment was something he didn’t venture to do. There were straps he knew what to do with: mechieti shed a little of their girth after a morning start, especially when they were traveling this hard; and a saddle that slipped more than Nokhada’s had been doing just before the dismount was a problem he didn’t want. Expert handlers moved through the company seeing to any mechieta the rider for one reason or another wasn’t able to see to; and just as the young man was attending to Nokhada’s harness, the discussion the senior security officers had been holding among themselves was breaking up. Banichi had left the group and was leading his mechieta along the edge of the company at a very purposeful stride while Jago and Cenedi went to speak to Ilisidi.

“Banichi-ji?”

“Everything is fine,” Banichi said cheerfully. “Our enemies are being fools.”

“Doing what?”

“Oh, nothing up here. Down the coast. The authorities have caughtone of Direiso’s folk on the Wiigin-Aisinandi line.”

On the train, Banichi meant.

“Illicit radio? Saying what?”

Banichi shot him a guarded, assessing kind of look. “That Tabini-aiji is fortifying Saduri plain and preparing to bomb Mospheiran cities. That he’s seizing Mogari-nai to have absolute control of the radar installations during the aforesaid operation, because he knows a retaliation is coming immediately after he bombs the island and the northern provinces are going to take the brunt of it.”

“That’s absolutely insane!”

“We’re quite sure it is, but it isindicative of Direiso’s objective. She wishes to seize Mogari-nai and the airstrip and say there’s nothing there because she’s thwarted the plot.”

“The plant at Dalaigi.” He had a sudden great fear of harm to Patinandi. “What if it’s a diversion, Banichi-ji? Are we protected there?”

“Oh, we are protecting all such places,” Banichi said. One of the men was adjusting harness, and Bren gave a distracted yank on Nokhada’s rein as she swung her hindquarters and refused cooperation. “We have very heavy security on those plants, especially in facilities where you’ve very diligently pointed out security problems, Bren-ji, and your eye is becoming quite keen in that regard.”

“One is grateful to know so, nadi-ji.”

“Once the report said bombs would fall, we became very much more concerned that the reserve here is a major target—because maintaining that falsehood means controlling this area within a certain number of hours or attacking government facilities within the same time, so they can say we moved the equipment. And Direiso has adherents among Messengers’ Guild officers, but notnecessarily among the membership. That we silenced that radio and were ready with statements laying out Direiso’s plans will at least throw water on the fire. Our press release isbeing routed through Mogari-nai and the local stations arecarrying the official broadcast. It may be significant, however, that Mogari-nai was the last major communication center to pass the aiji’s press release to the broadcast stations.”

It was ominous. Very much so. He made a motion of his eyes toward the heavens. “If theyhave bombs—”

“No, Bren-ji. I assure you, noaircraft will reach us. There are aircraft sitting ready to take action against any craft Direiso can send against us. We learned at Malguri, and we have taken precautions. Not mentioning Tano’s position, which is quiet, but very capable of defending itself. The fortress isancient. But for you alone to know—though possibly Direiso does—even the dust of Saduri is modern. They blow it on. For the casual hiker. This is more than a game reserve. If we’ve kept that secret from Mospheira, numerous people will be surprised.”

He was mildly shocked; and no, his government didn’t tell him everything: particularly the Defense Department with its touchy secrets. His mind raced through memories of dilapidated halls, a row of doors facing their bedrooms that didn’t open and didn’t have windows.

In this vast, open government reserve there were fences, he guessed, that were far more than low stone walls. And he had no idea what other electronic barriers might exist out here, or what those vans he’d seen parked behind the old fortress might contain, but Tano and Algini were surveillance specialists, he had guessed before this, while Banichi and Jago were surely what the Guild so delicately called, with entirely different meaning, technicians.

“We aren’t using the pocket coms to transmit any longer,” Banichi said. “Though I assure you reception is no problem. We listen to a mobile unit up near Wiigin talk to one east of the fortress and know all we need. Thistime, Bren-ji, we are not using a defense heavily infiltrated with the opposition, as we were at Malguri. As for what we need worryabout, there’s one other road that goes up the cliffs from Saduri Township. It supplies Mogari-nai, and tourists use it to tour the cannon fort. The aiji’s forces will keep that road open. Meanwhile—” Banichi’s voice, from rapidfire cataloging of assets, took on an airy quality. “Meanwhile, the dowager will assert her prerogative, as a member of the aiji’s household, to tour the facility. But we have to be careful. To dispossess the Messengers’ Guild of Mogari-nai would tread on Guild prerogatives. Even to save lives, ourGuild will not countenance that kind of operation. Politics, you understand. And in the balance of powers, it iswise to preserve those prerogatives.”

“One understands that much.” A Guild disintegrating would be very dangerous to the peace. As the fall of the Astronomers from credibility after the Landing had been catastrophic for atevi stability: for lords there were successors, but for the Guilds there were not. “Banichi-ji, the aiji does know, I hope, that we can receive data without the earth station. Surely he does know.”

“Yes. But Guild prerogatives demand it go through the Messengers’ Guild no matter where we receive it. The Messengers will bend, nand’ paidhi. Their rebellion will go on precisely as long as that Guild sees other entities defying the aiji with impunity, or until the fist comes down on them. The aiji can no longer ignore Hanks’ challenge to his authority.”

“So we are going to fight, there? The dowager is truly on our side?”

“Fight, nand’ paidhi? Ilisidiis on holiday at Saduri. The television says so quite openly. The television says, during her holiday, she will tour Mogari-nai.” The call was going out to mount up. “Saigimi’s death was a serious blow to Direiso. Tatiseigi’s appearance on television was a second. Badissuni’s attack of heartburn was a third, leaving Ajresi unopposed in the Tasigin Marid, and Badissuni very cooperative with the aiji, if he’s wise. The Messengers’ Guild admitting Ilisidi for a tour is a fourth. Direiso may strike in anydirection, but it’s the business of aijiin to settle their affairs and then the Guilds have no difficulty arranging their policies. Believe me that the Messengers are no different from ourGuild.”

Banichi made his mechieta extend a leg and got up, in that haste the maneuver needed. Others were getting up. Bren had Nokhada kneel and as he rose, turned and landed in the saddle, he saw Jase attempt to do the same.

Attempt. Jase failed, was left clinging to the saddle ring with one foot hung and the other off the ground as the mechieta rose and tried to turn full circle in response to Jase’s unwitting grip on the rein. It was a dangerous halfway, from which a man could fall with his foot still trapped; but Haduni was there instantly to put a hand under Jase and boost him up, disheveled and with his braid loosening, but safe. Jase still pulled, and the mechieta resisted, lifted his head and turned another circle until Jase apparently realized it was his own fault and slacked the grip on the rein.

“It took me a while,” Bren said.

Jase still looked scared. Well a man could be. And dizzy. For a man who had trouble with the unclouded sky and kept taking motion sickness pills, the mechieta turning while he was off balance was not, Bren was sure, a pleasant thing.

“You’re doing fine,” Bren said.

And with no warning but a ripple of motion through the herd Nokhada spun and joined the others in a rush after Ilisidi, who had taken off. Bren looked back, scared for Jase, but he had stayed on. Jago fell back to join him as the herd sorted itself out, Nokhada fought the rein to get forward, and Banichi rode ahead of him.

But the rush settled into a run for a good long while. Ilisidi, damn her, was having the run she’d wanted, a perverse streak she had, a desire to challenge a man’s sense of self-preservation, never mind Jase was fighting to stay on and scared out of good sense.

He dropped further back, a fight with Nokhada’s ambitions, and came past the boy from Dur, who was riding with a death grip on the saddle straps and excitement in his eyes. He came alongside Jase, then, who was almost hindmost in the company. Jase was low and clinging to the saddle, his whole world doubtless shaking to the powerful give and take of the creature that carried him.

“What are we doing?” Jase yelled at him. “Why are we running, nadi?”

“It’s all right!” he yelled back. And yelled, in Ragi, what he’d said on the language lessons when Jase had reached the point of anger: “Call it practice!”

Jase, white-faced and with terror frozen on his features, began suddenly to laugh, and laugh, and laugh, until he wondered if Jase had gone over the edge. But it wasfunny. It was so funny he began to laugh, too; and Jase didn’t fall.

In a while more, as Babsidi ran out his enthusiasm for running, they slowed to that rocking pace the mechieti could hold for hours, and then Jase, having been through the worst, grew brave enough to straighten up and try to improve his seat.

“Good!” Bren said, and Banichi said, riding past him, “Well done, Jase-paidhi!”

Jase glanced after Banichi with a strange look on his face, and then seemed to decide that it wasa word of praise he’d just heard. His shoulders straightened.

The mechieti never noticed. The boy from Dur dropped back to ride with them and with Haduni and Jago. But then Nokhada decided she was going to go forward, giving little tosses of her head and moving as if she could jump sideways as easily as forward, meaning if she found an excuse to jump and bolt, she would.

Bren let her have her way unexpectedly and touched his heel to her ribs, which called up a willing burst of speed around the outside of the herd and up to the very first rank. She nipped into place with Ilisidi and Cenedi, where she was sure she belonged.

“Ah,” Ilisidi said. “nand’ paidhi. Did he survive?”

“Very handily,” he said, and knew then the dowager had kept onepromise she’d made in coming here, to give the new paidhi the experience he’d had.

And Jase had laughed. Jase had sat atop a mechieta’s power and stayed on, Jase had been told by a man he hadn’t trusted that he had done quite well, and Jase was still back there, riding upright and holding his own under a wide open and cloudless sky.

And by that not inconsiderable accomplishment Jase was better prepared if they had to move: it waspractice; and practice like that had been life and death for him—in a lot of ways.

The sun declined into the west until it shone into their eyes and made the land black, and nothing untoward had happened. The sun declined past the edge of the steep horizon toward which they were climbing, and the light grew golden and spread across the land, casting the edges of the sparse, short grasses in gold.

Suddenly, with the topping of a rise, a white machine-made edge showed above the dark horizon, far distant.

Mogari-nai: the white dish of the earth station, aimed at the heavens. Beyond the dish in that strange approach to dusk, the blue spark of warning lights. Microwave towers aimed out toward the west, a separate establishment.

They rode closer, and now the sky above the darkening land was all gold, the sun sunk out of sight. One could hear in their company the sounds that had been their environment all day: the moving of the mechieti, in their relentless, ground-covering strides; the creak of harness; the rare comment of the riders. Somewhere below their sight the sun still shone, and they discovered its rim again as, between the shadow of cliffs falling away before them, the ocean shone faintly, duskily gold—no longer Nain Bay, but the Strait of Mospheira.

The last burning blaze of the sun then vanished still abovethe horizon. The mountains of Mospheira’s heart, invisible in the distance, were hiding the sun in haze.

“A pretty sight,” Ilisidi said.

If they had not struck their traveling pace when they had, they would have arrived well after dark. Ilisidi, Bren thought, had wanted the daylight for this approach to the earth station and its recalcitrant Guild.