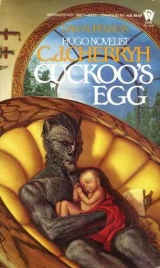

Текст книги "Cuckoo's Egg"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

Cuckoo's Egg

C.J. Cherryh

DAW Books, Inc.

Donald A. Wollheim, Founder

375 Hudson Street,

New York, NY 10014

Elizabeth R. Wollheim

Sheila E. Gilbert

Publishers

www.dawbooks.com

in cooperation with

SEATTLE BOOK COMPANY

www.seattlebook.com

Produced by

RosettaMachine

www.rosettamachine.com

Cuckoo's Egg

The Finest in

DAW Science Fiction

from C.J. CHERRYH:

THE ALLIANCE-UNION UNIVERSE

The Company Wars

DOWNBELOW STATION

The Era of Rapprochement

SERPENT'S REACH

FORTY THOUSAND IN GEHENNA

MERCHANTER'S LUCK

The Chanur Novels

THE PRIDE OF CHANUR

CHANUR'S VENTURE

THE KIF STRIKE BACK

CHANUR'S HOMECOMING

CHANUR'S LEGACY

The Mri Wars

THE FADED SUN: KESRITH

THE FADED SUN: SHON'JIR

THE FADED SUN: KUTATH

Merovingen Nights (Mri Wars period)

ANGEL WITH THE SWORD

The Age of Exploration

CUCKOO'S EGG

VOYAGER IN NIGHT

PORT ETERNITY

The Hanan Rebellion

BROTHERS OF EARTH

HUNTER OF WORLDS

ii

Cuckoo's Egg

THE MORGAINE CYCLE

GATE OF IVREL (#1)

WELL OF SHIUAN (#2)

FIRES OF AZEROTH (#3)

EXILE'S GATE (#4)

THE EALDWOOD FANTASY NOVELS

THE DREAMSTONE

THE TREE OF SWORDS AND JEWELS

OTHER CHERRYH NOVELS

HESTIA

WAVE WITHOUT A SHORE

THE FOREIGNER UNIVERSE

FOREIGNER

INVADER

INHERITOR

PRECURSOR

DEFENDER*

EXPLORER*

*Forthcoming

iii

Cuckoo's Egg

Copyright © 1985 by C.J. Cherryh.

All Rights Reserved.

DAW Book Collectors No. 646.

DAW Books are distributed by Penguin Putnam Inc.

Microsoft LIT edition ISBN: 0-7420-9098-1

Adobe PDF edition ISBN: 0-7420-9100-7

Palm PDB edition ISBN: 0-7420-9170-8

MobiPocket edition ISBN: 0-7420-9099-X

Ebook editions produced by

SEATTLE BOOK COMPANY

Ebook conversion and distribution powered by

www.RosettaMachine.com

All characters and events in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead is strictly coincidental.

iv

Cuckoo's Egg

Electronic format made

available by arrangement with

DAW Books, Inc.

www.dawbooks.com

Elizabeth R. Wollheim

Sheila E. Gilbert

Publishers

Palm Digital Media

www.palm.com/ebooks

v

Cuckoo's Egg

Table of Contents

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

vi

Cuckoo's Egg

I

He sat in a room, the sand of which was synthetic and shining with opal tints, fine and light beneath his bare feet. The windows held no cityview, but a continuously rotating panorama of the Khogghut plain: a lie. Traffic noise came through.

His name was Duun. It was Dana Duun Shtoni no Lughn. But Duun was enough for day-to-day. They called him other things. Sey:general. Mingi: lord. Or something very like. Hatani: that was another thing. But Duun was enough now. There was only one. Shonunin the world over knew that, and knew him; and when the door chimed and they came to bring the alien to him, whose who carried it would not look him in the eyes, not alone for the scars that a shonun could see, the pale smooth marks traced through the fur of half his face like the limbs of a lightning-blasted tree, the marks that twisted his right ear and left his mouth quirked in permanent irony and one eye staring out of ruin.

He was Duun, of Shanoen.He reached out hands one of which was marred, like his face, and took the closed carrier that they gave him, marking how their ears slanted back and how they turned their heads from his for horror– not of what they saw: they were meds, and had seen deformity. It was the force in him: like a great wind, like a great heat in their faces.

But his hands were gentle when he took the carrier from them.

They went away, appalled and forgetting courtesies.

He waved the door shut and set the carrier on the table-rise, opened it and gathered the small bundled thing from it.

* * *

Shonunin were naked when they were born, but downed in silver that quickly went to dapples and last of all to gray body coat and black on limbs and ears and crest. Duun held the creature on its discarded wrapping, on his knees; and its downless skin was naked and pink as 1

Cuckoo's Egg

something lately skinned, except for a thatch of nondescript hair atop its skull. It waved soft limbs in helpless twitches. Its eyes were shut, in a face flat and not unlike a shonun; between its legs an outsized organ of curious form and various (they said) function. Its mouth worked restlessly, distorting the small face. And Duun touched it with the sensitive pads of his fingers, with the four fingers of his left hand and the two of his maimed right, exploring the hot, smooth feel of the bandage-patched belly, the chest, the limbs. With the merest tip of a claw he drew down its soft lip to inspect its mouth– nothing but toothless gums, for it was mammalian.

With the claw he lifted the lid of a sleeping eye; he saw it white and milky, centered with blue, restless in natural shiftings. He touched the convolutions of the stiff, small ears; explored the visible organ and discovered reaction: so it was sensitive. That was of interest. He examined the fat, clawless feet, all one pad as far as the toes. Unfurled a five-fingered hand with the careful touch of a single clawed finger, and the tiny fist clenched again, stubbornly. It waved its limbs. Fluid shot from the organ and fouled Duun's clothes.

Any shonun would have flinched seeing that. But Duun gathered up the wrap about the infant and mopped at himself patiently, with infinite patience. So. Likewise shonun infants performed such obscenities, if more discreetly. It let out cries, soft and weak and meaningless as all infant cries. It struggled with less strength than his own infants had shown.

He knew what it would be, grown. He knew its face. He knew every aspect of its body. He gathered it against his breast in the stinking blanket and rose, went to the package they had brought him that morning and left on the riser by the bed. He held the softly crying creature in the crook of his left arm. for he was still more able with the right hand, two-fingered as it was. He managed to open the case and to warm the milk– not milk of shonunin; by synthesis the meds provided, of their own ingenuity.

There was data, which had come days ago; he had memorized it. The creature wailed; so shonunin wailed, exercising infant lungs. And it breathed the air shonunin breathed: and perhaps its gut would take the meat shonunin ate one day. The meds thought that this was the case. The teeth that would grow would, some of them, be pointed like the major teeth of a shonun. "Hush, hush," he told it, joggling it against his chest. He 2

Cuckoo's Egg

drew the warmed bottle from the case and thrust the nipple into the soft mouth that quested among the blankets. It suckled noisily and quieted, and he crossed the sand to the riser he had left, sat down cross-legged, rocking it, whispering to it.

"Be still, be still."

Its eyes closed in contentment; it slept again, fed and held. It could not, like a shonun, be taken for granted. He was delicate with it. He laid it finally in the bowl of his own bed and sat beside it, watching its small movements, the regular heaving of its tiny round belly; and when the view in the windows changed and became the nightbound sea, he still watched.

He would not soon tire of watching. He did not bathe. He was fastidious, but he inhaled the smell of it and the soiled blanket, the smells of its food and its person, and did not flinch, having schooled himself against disgust.

* * *

They were dismayed when they came, the meds– to deal with him, to examine the infant and to take it back to the facility down the hall to weigh it and monitor its condition. He stalked after them as they carried it in its closed case; he offended their nostrils with his stink.

And never once in all this dealing would they meet his eyes, preferring even the face of the alien to the chance of looking up into the stark cold stare he gave to them and all their business.

They weighed the infant, they listened to its breathing and its heart, they asked quietly (never glancing quite at him) whether there had been difficulty.

"Duun-hatani, you might rest," the chief of medicine said the second day that they came for the infant. "This is all routine. There's no need. You might take the chance to—"

"No," Duun said.

3

Cuckoo's Egg

"There—"

"No."

There was uncomfortable silence. For days Duun had looked at them without answer; now the chief cast a searching, worried glance full into his eyes, and immediately afterward found something else to occupy herself.

Duun smiled for the first time in those days, and it was a smile to match the stare.

* * *

"You dismay them, Duun," the division chief said.

Duun walked away from the desk on which Ellud sat, gazed at the false windows, which showed snowfall. Ice formed on the branches of a tree above a hot spring. The sun danced in jeweled branches and the steam rose and curled. Duun looked back again, the thumb of his maimed hand hooked behind him to that of the whole one, and discovered another man who preferred to study something just a little behind his shoulder. The false sunlight, it might be. Anything would have served. "It's in very good health," Duun said.

"Duun, the staff—"

"The staff does its job." Never once had the eyes focused on him, quite.

Duun drew a deep breath. "I want Sheon."

"Duun—"

"Sheon belongs to Duun, doesn't it? I tell you that it does."

"Security at Sheon—"

"I stink. I smell. Notice it, Ellud?"

4

Cuckoo's Egg

Long pause. "The estate—"

"You offered me anything. Wasn't that what you said? Any cooperation?

Would any shonun in the world prevent me anything– if I want a woman; if I want a man; if I want money or your next of kin, Ellud– if I want the president turned out naked and the treasury to walk in—"

"You're hatani. You wouldn't."

Duun looked again at the false spring bubbling up in its wintry vapors.

"Gods! but you do trust me."

"You're hatani."

He looked back with the first clear-eyed stare he had used in years. But not even that could hold Ellud's gaze to his. "I'm begging you, Ellud. Do I have to beg? Give me Sheon."

"Settlers have moved there. Their title's valid by now."

"Move them out. I want the house. The hills. Privacy. Come on, Ellud…

you want me to camp in your office?

Ellud did not. They had been friends. Once. Now Duun saw the guarded lowering of the ears. Like shame. Like a man taking a chance he wanted.

Badly. At any cost.

"You'll get it," Ellud said. Never looking at him. Ellud's claws extended slightly, raked papers aside as he looked distractedly at the desk about him. "I'll do something. I'll see to it."

"Thanks."

That got the eyes up. A wounded look. Appalled like the rest. The agony of friendship.

Of wounded loyalties.

5

Cuckoo's Egg

"Give it up," Ellud asked, against self-interest; against all interests. The loyalty jolted, belated as it was.

"No." For a moment then, eye to eye, no flinching from either side. He remembered Ellud under fire. A calm, cool man. But the gaze finally shifted and something broke.

The last thing.

Duun walked out, freer, because there was nothing left. Not even Ellud.

Just pain. And he wrapped that solitude about him, finding it appropriate.

* * *

He came to Sheon's hills in the morning, in a true morning with the sun coming up rose and gold over the ridge; and the wind that blew at him on this grassy flat was the wind of his childhood, whipping at his cloak, at the gray cloak of the hatani, which he wrapped about him and the infant.

Ellud's aide showed distress, there on the dusty road that led toward the hills, in the momentary stillness of the craft which had brought them there, over in the meadow. The aide's ears lay flat in the wind, which blew his neatly trimmed crest and disarranged the careful folds of his kilt. The wind was cold for a citydweller, for a softhands like him. "It's all right," Duun said. "I told you. There's no way up but this. You don't have to wait here."

The aide turned his face slightly toward the countryfolk who gathered out of the range of hearing, who gathered in knots, families together, uncaring of the cold. The aide looked back again, walked toward the gathered crowd waving his arms. "Go away, go away, the mingi has no need of you. Fools," he said then, turning back, for they gave only a little ground.

He stooped and gathered up from the roadside the little baggage there was, slung the sack from his shoulder. His ears still lay back in distress.

"Hatani, I will walk up with you myself."

It was a wonder. The aide met his eyes with staunch frankness. Ellud chose such young folk, still knowing the best, the most honest. Duun felt for a moment as if the sun had shone on him full; or perhaps it was the 6

Cuckoo's Egg

smell of true wind, with the grass-scent and the cleanness. He felt a motion of his heart toward this young man and it ached.

But he grinned, old soldier that he was, and glanced at the uphill road, for this time he was the one to flinch, from the youth's innocence and worship.

"Give me the sack," he said, and stripped the carry-strap from the young man's shoulder and took it to his own, his right. The infant occupied his left arm, warm and moving there, nuzzling wormlike among its swaddlings beneath his cloak.

"But, hatani—"

"You're not going. I don't need you."

He walked away.

"Hatani—"

He did not look back. Did not look at the mountainfolk who lined the road near the copter. Some of them were the displaced, he was sure. Some of them had held Sheon, having gotten it since he was renunciate. Now they were abruptly dispossessed. He felt their eyes, heard their whispers, nothing definite.

"Hatani," he heard. And: "Alien."Whisper they need not. He felt their eyes trying to penetrate his cloak. They came to wonder what he was as much as they wondered about what he brought. "Hatani." There was respect in that. "What happened to his face?" a child asked.

"Hush," an adult said. And there was a sudden, embarrassed hush. It was a child. It had not learned what scars were. It was only honesty.

Duun did not look at them. Did not care. He was hatani, renunciate. His weapons were at his side beneath the cloak. He asked one thing of the world. These hills. This place.

A little peace.

7

Cuckoo's Egg

That a hatani dispossessed them– The countryfolk living at Sheon had surely thought their title secure. The land was fallow; the house vacant; ten years renunciate and it was theirs by law.

But it was what he had told Ellud: there was nothing he could not ask and obtain, nothing in all the world

He felt their eyes. Perhaps they expected him to speak. Perhaps they expected him to care, to offer words to reassure them.

But he only walked past them up the road, the dusty road to the heights and the house made of native stone, deep within the hills.

He heard the copter lift. It beat away with small thumps like heartbeats echoing off the mountainside. It had come and gone often here yestereve and three days before, with other craft, seeing to provisions, to special equipment, to all such things as satisfied Ellud and Ellud's ilk.

Nuisance, all of it.

* * *

He prepared himself. He knew that Sheon would have changed. He gathered up his resolve in this as in other things. He needed virtue. He sought it in abnegation. He sought it in lack of caring, when he came, in full noon, to the mountain heights, and discovered the things countryfolk had done to Sheon, which he expected: a sprawl of new rubble-stone building, which destroyed the beauty Sheon had once been, a creation of smooth artistry indistinguishable from the living rock of the mountain wall that flanked it. The house sprawled now, artless and utilitarian, the yard about it cleared and dusty. He was not dismayed.

Only when he came inside and discovered what Ellud and his crews had done– that, that afflicted him. Instead of the country untidiness he had expected (different from the time of his childhood, of stones carefully polished, of spacious halls and a sand-garden where the wind made patterns), the government had worked sterility, lacquered the stone walls, sanded the floors in white, not red, installed a new kitchen, new 8

Cuckoo's Egg

furnishings, all at great expense; and the smell of it was new and pungent with fixatives and paint and new-baked sand.

He stood there, in this clean, sterile, unremembered place, with its abundant stores, its furniture new from the city—

For the infant. Of course, for the infant. The meds feared for its health.

They wanted sanitation.

And destroyed– destroyed—

He stood there a long, long time, in pain. The infant squirmed and began to cry. And he was very careful with it in his anger, as careful as he had ever been. He searched the cabinets for new cloths; fround the cradle prepared—

The infant soiled itself. He knew the cry, smelled the stink, which had surrounded him, stronger than the lacquer and dry-dust smell of sand.

He laid it down on the sand; he put off his cloak and laid his weapons down on a riser near the fireplace. He listened to it scream. It had grown.

The voice was louder, hoarser, the face screwed up in rage.

He took cloths and wet them and knelt and cleaned its filth in starkest patience; he heated the formula and fed it till it slept. He walked aimless in the halls afterward, smelling the stink it had left on him, and the stink of new plaster, new lacquer, new furniture.

He had run barefoot in these halls, laughed, played pranks with a dozen sibs and cousins, rolled on the floor-sand, till exasperated elders flung them out into a yard well shaded with old trees.

The trees were gone. The new wing stood where the oldest tree had been.

So much for homecomings.

* * *

9

Cuckoo's Egg

He made a fire. There was that one thing left untouched, the old stones of the hearth he had sat by as a child, and there were scraps of demolished outbuildings and fences, in a towering pile near the rocks. He made a fire of them, burning others' memories of home.

He took the infant outside with him, well wrapped against the cold; he took it about the house with him, in the kitchen, at last before the fire itself; he sat on the clean deep sand before the hearthstones and held the infant in his lap.

He had grown accustomed to it. The flat, round face no longer disturbed him. The smell was his smell, compounded of its sweat and his. Demon eyes looked up at him. The face made grimaces meaningless to both of them in the wavering firelight, the leaping flames.

He took its skull between his hands, the whole and the maimed one, and he was careful as if the skull had been eggshell instead of bone. He smiled, drawing back his lips from his teeth, and gazed into eyes which perhaps saw him, perhaps not.

"Wei-na-ya," he sang to it, "wei-na-mei,"– in a hoarse male voice unapt for lullabies; little bird, little fish– the house had heard that song before.

"Hei sa si-lan-nei…." Do not go. The wind is cold, the water dark, but here is warm."Wei-na-ya, wei-na-mei."

And "Sha-khe'a," he sang, but softly, like the lullaby, which was a hatani song.

It was the deathsong. He sang it like the lullaby. He smiled, grinned into its face.

"Thou art Haras," he said to the awful, demon face, to the slittted eyes with their centers like stormcloud. It was the sadoth he spoke, the language of his hill-dwelling ancestors. "Thou art Haras. Thornis your name."

It gazed solemnly up at him.

10

Cuckoo's Egg

Unafraid.

It waved its hands. He,Duun reminded himself, He. Haras. Thorn. The wind howled about the house, skirled in the chimney and set the flames to flickering in the hearth.

He grinned and rocked the child and did a thing which would have chilled the blood of any of the countryfolk who doubtless huddled together in their dispossession; or the meds; or Ellud in his fine city apartment.

He held it as if it were a shonun child and washed its eyes with his tongue (they tasted salt and musty). There was nothing he spared himself, no last repugnance he did not overcome. Such was his patience.

11

Cuckoo's Egg

II

They came from the capital. Copters landed, and meds made the long trek uphill carrying their instruments; and downhill going away. They were not pleased. Perhaps the countryfolk frightened them, gathering in their sullen watchfulness at the foot of the road, where the aircraft landed.

They came and went away again.

Duun held the infant, talked to it as he watched them go, mindless talk, as one did with children.

It. Haras. Thorn.

"Duun," Thorn said, infant babble. "Duun, Duun, Duun."

Thorn made busy chaos on the sand before the hearth. His cries were loud, ear-splitting; shonunin were more reserved. He still soiled himself. When this would cease Duun did not know. How to teach him otherwise he did not know. Thorn's appetite had changed; his sleep was longer, to Duun's relief.

"Duun, Duun, Duun," the infant sang, on his back before the fire. And grinned and laughed when Duun poked him in the belly, squealed, when Duun used a clawtip. Laughed again. Enjoyed his belly rubbed, fat round belly which began to hollow now, the limbs to lengthen. "Duun." Duun leaned forward, nipped at Thorn's neck. Thorn grabbed his ears, and Duun sat back, escaping the infant grip, disheveled. He had let his crest grow; it sheeted raggedly down his back and strayed now in front of his ears.

He went for the throat again on hands and knees and Thorn squealed and kicked. Clawed with small fat hands, with nails which were all the defense he had.

Duun laughed aloud, well-pleased.

* * *

12

Cuckoo's Egg

Thorn ran, ran, ran on tottering legs, out of doors, on the dusty earth where outbuildings had been; naked in the warmth of spring.

Duun knelt. No one nowadays saw Duun's body, the lightning-blasted scars of his right arm, the scars that skeined across his side and leg. But here he wore no more than the small-kilt, in the warmth, with the hiyi flowering by the back door and drifting blossoms down pink as Thorn's smooth skin. Infant hair had gone, come in gold, darkened again in winter metamorphosis. Perhaps it was seasonal; perhaps a phase of Thorn's life.

Duun held out his arms to Thorn and Thorn laughed as he plunged into Duun's arms, all dusty-smelling.

"Again," Duun said, and set him upright, crouching again a little distance off to make Thorn run. Infant legs tried and failed, exhausted. Duun caught him, hugged him, licked his mouth and eyes, which Thorn did to him when Thorn had stopped laughing and gasping, clenching small five-fingered fists into Duun's trailing crest and the shorter hair of his forelock, and digging his face for a sly nip into the hollow of Duun's neck when he got the chance, but Duun ducked his head aside and got in a nip first.

Small unclawed feet drove at his lap, the small body strained and Thorn ducked down to bite him ungently in the chest.

"Ah!" Duun cried, seizing him in both hands, kneeling, lifting him kicking and squealing aloft at arm's length. "Ah! Devious!"

He hugged him again and Thorn bit again. He had gained teeth, and strength, but they were not teeth like Duun's. Duun bit at fingers and Thorn caught Duun's mouth and pushed back his lip to try his fingers on Duun's larger, sharper teeth. Duun nipped and Thorn rescued his hand and squealed.

* * *

There were more visits. "Bye, bye, bye," Thorn bade the meds sullenly from the porch. He squatted down naked as he was and grimaced then. He had bit the chief med, and the med had come within a little of flicking an impudent youngster hard on the nose.

13

Cuckoo's Egg

But the med had stopped himself. Duun was standing there, hatani-cloaked in gray, arms folded.

The meds went away. Thorn made a rude sound and urinated on the step.

Duun went and snapped him soundly on the ear with thumb and forefinger. Thorn wailed.

"Bad," said Duun. The wail went on. Duun went into the house, into the kitchen and got his hand wet in the sink. Thorn followed, naked, holding hands out, wailing all the way and dancing in his distress.

"Shut up," Duun said. And flicked cold water in Thorn's face. Thorn blinked and howled and clawed frantically at Duun's legs, not in rage. Pick me up, that meant.

Duun picked him up, armful that he had become, rocked him with a swinging of his body in that way he had learned the infant liked. A small face nuzzled its way to his neck; this did not always mean biting. This time it did not. Thorn clung to him and snuffled, soiling his cloak with running eyes and nose.

"You were bad," Duun said. To such simplicities the philosophy of hatani bent nowadays. He swung from side to side and the sobs stopped. The thumb went in Thorn's mouth, irrepressible, though Thorn ate meat now, which Duun chewed for him and spat into his mouth. ("Not advisable," the meds said, obsessed with disease. But he did it, which was an old way, a hill way, and easier than urging a spoon past Thorn's dodging mouth, or cleaning up when Thorn fed himself and smeared it everywhere. Duun's mother and father had done this for him. He took perverse pleasure in performing this dutiful service. It shocked the meds. That gave him perverse pleasure too. He smiled at the meds. It was strange. They had become familiar with him. They looked him in the eyes, at least more than once in the visit. "Elludmingi sends regards," they said. "I sent mine," he said in return. And perversely added: "So does my son." Thatsent them on their way in haste. Doubtless to take notes.)

14

Cuckoo's Egg

He rocked Thorn and sang to him, absently: "Wei-na-mei, wei-na-mei."

And Thorn grew quiet in his arms. "You're getting too big to hold," Duun said. "Too big to make puddles on the step."

That night, when they sat before the fire (the spring nights were cold) Thorn crawled into his lap and sat there a while; and got up on his feet in the triangle between Duun's crossed legs and touched Duun's face, the scarred side. Duun caught the hand with his maimed one. And let it go.

"It's a scar," Duun said.

He did not prevent the exploration. He made himself patient. He shut his eyes and let Thorn do what he liked, until Thorn pulled savagely on both his ears, which was challenge. Duun's eyes flashed open.

"Ah!"Duun cried, drawing back his lips in a grimace. Thorn recoiled and stumbled on Duun's legs; Duun caught him in mid-fall and rolled with him, rolled holding him in his arms, never coming on him with his weight.

Thorn screamed, and gasped, and when Duun bit, bit back, and screamed and squealed till Duun clamped a hand over his mouth and held it there.

Thorn grew still. The eyes stayed wide with shock. So. So. Fright, not fight.

Duun gathered him to his breast and licked his eyes till Thorn had begun to pant, recovering his lost breath. For a moment Duun was worried. Small hands clutched at him.

He gripped Thorn by both arms and held him up. Grinned. Thorn refused to be appeased.

That night Thorn waked howling at Duun's side, short sharp yelps, gasps for breath. "Thorn!" Duun cried, and turned on lights and snatched him up, thinking he had rolled on the infant and hurt him in some way; but it was nightmare.

Thorn held to him. It was Duun Thorn feared. That was the nightmare.

15

Cuckoo's Egg

"Ah," Duun cried, falling back, dragging Thorn atop him. "Ah! you hurt me! You hurt me—" To give him the upper hand. He had no pride in this.

"Duun," Thorn cried and snuggled close.

Sometimes genes were truer than teaching. Alien. Thorn clung to what had frightened him.

"Duun, Duun, Duun—"

Duun held him. It was all Thorn understood.

* * *

There was a day, in the morning bath, that Thorn noticed his own naked skin. Thorn scrubbed at Duun's belly and at his own with a rough-textured sponge. Dropped the sponge and put both hands on his own belly, rubbed it thoughtfully. When he looked up thoughts passed in his milk-and-storm eyes, with a little knitting of his brow. "Slick," he said of himself. His speech did not go as fast as a shonun child. But there was a difference of mouths and tongues. "Slick."

Perhaps Thorn wanted to ask, if his young mind had thought of it, when his own pelt would begin to grow. The hair on his head was abundant, tousled curls, which had finally settled on a faded, earthy brown. The eyes had never changed. It was a dangerous time.

Duun took Thorn from the bath and held him in his left arm, hugged him close in front of the mirror. Thorn had seen mirrors. He had one for a toy.

He had seen this one many times.

Today there was distress in young Thorn's eyes, and thoughts were going on. Thorn had never seen a shonun child. He had never seen other shonunin, except the meds. Perhaps some terrible thing was dawning on his mind, put together of little wordless pieces, images in mirrors, smooth bellies, a facility for making water in a long, long arc, which was for a time his nuisancefully chiefest talent. He spread his five-fingered hand at Thorn-in-the-mirror, in a way that should bring claws and did not; he grimaced at this Thorn as if to frighten him to flight. (Go away, ugly Thorn.) He flexed the fingers yet again. Made faces.

16

Cuckoo's Egg

Duun turned them both away. Bounced him to distract him.

After that Thorn did not mention the difference of their skins. Only from time to time there were small moments which Duun caught: a moment of rest when Thorn, lying beside Duun, reached and stroked his arm, turning the fur this way and that. Another when Thorn, finding Duun's hand conveniently palm up, dragged it closer to him across Duun's lap and played with it, fingering the dissimilar geometries of the palm, working doggedly at the fingers to make the claws come out. Duun cooperated. It was his right hand. It was not the deformity Thorn explored, but an ability which surely Thorn envied; and Duun was suddenly aware of a silence within the child, a secrecy which had grown all unawares, that small walled-off place which was an independent mind. Thorn had arrived at selfhood, a self which came out to explore the world and retreated with scraps of things which had to be examined with care, compared (sign of a complex mind) against other truths: Thorn had arrived at self-defense, disappointed in his body, it seemed. Aware of his own deformity. And not, truly, aware of Duun's. Duun was Duun. Duun had always had scars; they were part of Duun as the sun was part of the world. There was no past.