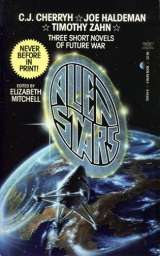

Текст книги "The Scapegoat "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 4 страниц)

The elf seemed to gaze into infinity. “We don’t want to fight anymore.”

“Neither do we. Is this why you came?”

A moment the elf studied the scientist, and said nothing at all.

“What’s your people’s name?” the scientist asked.

“You call us elves.”

“But we want to know what you call yourselves. What you call this world.”

“Why would you want to know that?”

“To respect you. Do you know that word, respect?”

“I don’t understand it.”

“Because what you call this world and what you call yourselves isthe name, the right name, and we want to call you right. Does that make sense?”

“It makes sense. But what you call us is right too, isn’t it?”

“Elves is a made-up word, from our homeworld. A myth. Do you know myth? A story. A thing not true.”

“Now it’s true, isn’t it?”

“Do you call your world Earth? Most people do.”

“What you call it is its name.”

“We call it Elfland.”

“That’s fine. It doesn’t matter.”

“Why doesn’t it matter?”

“I’ve said that.”

“You learned our language very well. But we don’t know anything of yours.”

“Yes.”

“Well, we’d like to learn. We’d like to be able to talk to you your way. It seems to us this is only polite. Do you know polite?”

“No.”

A prolonged silence. The scientist’s face remained bland as the elf’s. “You say you don’t want to fight anymore. Can you tell us how to stop the war?”

“Yes. But first I want to know what your peace is like. What, for instance, will you do about the damage you’ve caused us?”

“You mean reparations.”

“What’s that mean?”

“Payment.”

“What do you mean by it?”

The scientist drew a deep breath. “Tell me. Why did your people give you to one of our soldiers? Why didn’t they just call on the radio and say they wanted to talk?”

“This is what you’d do.”

“It’s easier, isn’t it? And safer.”

The elf blinked. No more than that.

“There was a ship a long time ago,” the scientist said after a moment. “It was a human ship minding its own business in a human lane, and elves came and destroyed it and killed everyone on it. Why?”

“What do you want for this ship?”

“So you do understand about payment. Payment’s giving something for something.”

“I understand.” The elvish face was guileless, masklike, the long eyes like the eyes of a pearl-skinned Buddha. A saint. “What will you ask? And how will peace with you be? What do you call peace?”

“You mean you don’t think our word for it is like your word for it?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, that’s an important thing to understand, isn’t it? Before we make agreements. Peace means no fighting.”

“That’s not enough.”

“Well, it means being safe from your enemies.”

“That’s not enough.”

“What is enough?”

The pale face contemplated the floor, something elsewhere.

“What isenough, Saitas?”

The elf only stared at the floor, far, far away from the questioner.

“I need to talk to deFranco.”

“Who?”

“DeFranco.” The elf looked up. “DeFranco brought me here. He’s a soldier; he’ll understand me better than you. Is he still here?” The colonel reached and cut the tape off. She was SurTac. Agnes Finn was the name on her desk. She could cut your throat a dozen ways, and do sabotage and mayhem from the refinements of computer theft to the gross tactics of explosives; she would speak a dozen languages, know every culture she had ever dealt with from the inside out, integrating the Science Bureau and the military.

And more, she was a SurTac colonel, which sent the wind up deFranco’s back. It was not a branch of the service that had many high officers; you had to survive more than ten field missions to get your promotion beyond the ubiquitous and courtesy-titled lieutenancy. And this one had. This was Officer with a capital O, and whatever the politics in HQ were, this was a rock around which a lot of other bodies orbited: thisprobably took her orders from the joint command, which was months and months away in its closest manifestation. And that meant next to no orders and wide discretion, which was what SurTacs did. Wild card. Joker in the deck. There were the regs; there was special ops, loosely attached; there were the spacers, Union and Alliance, and Union regs were part of that; beyond and above, there was AlSec and Union intelligence; and that was this large-boned, red-haired woman who probably had a scant handful of humans and no knowing what else in her direct command, a handful of SurTacs loose in Elfland, and all of them independent operators and as much trouble to the elves as a reg base could be.

DeFranco knew. He had tried that route once. He knew more than most what kind it took to survive that training, let alone the requisite ten missions to get promoted out of the field, and he knew the wit behind the weathered face and knew it ate special ops lieutenants for appetizers.

“How did you make such an impression on him, Lieutenant?”

“I didn’t try to,” deFranco said carefully. “Ma’am, I just tried to keep him calm and get in with him alive the way they said. But I was the only one who dealt with him out there, we thought that was safest; maybe he thinks I’m more than I am.”

“I compliment you on the job.” There was a certain irony in that, he was sure. No SurTac had pulled off what he had, and he felt the slight tension there.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“ Yes, ma’am. There’s always the chance, you understand, that you’ve brought us an absolute lunatic. Or the elves are going an unusual route to lead us into a trap. Or this is an elf who’s not too pleased about being tied up and dumped on us, and he wants to get even. Those things occur to me.”

“Yes, ma’am.” DeFranco thought all those things, face to face with the colonel and trying to be easy as the colonel had told him to be. But the colonel’s thin face was sealed and forbidding as the elf’s.

“You know what they’re doing out there right now? Massive attacks. Hitting that front near 45 with everything they’ve got. The Eighth’s pinned. We’re throwing air in. and they’ve got somewhere over two thousand casualties out there and air-strikes don’t stop all of them. Delta took a head-on assault and turned it. There were casualties. Trooper named Herse. Your unit.” Dibs. O God. “Dead?”

“Dead.” The colonel’s eyes were bleak and expressionless. “Word came in. I know it’s more than a stat to you. But that’s what’s going on. We’ve got two signals coming from the elves. And we don’t know which one’s valid. We have ourselves an alien who claims credentials– andcomes with considerable effort from the same site as the attack.”

Dibs. Dead. There seemed a chill in the air, in this safe, remote place far from the real world, the mud, the bunkers. Dibs had stopped living yesterday. This morning. Sometime. Dibs had gone and the world never noticed.

“Other things occur to the science people,” the colonel said. “One which galls the hell out of them, deFranco, is what the alien just said. DeFranco can understand me better. Are you with me, Lieutenant?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“So the Bureau went to the secretary, the secretary went to the major general on the com; all this at fifteen hundred yesterday; and theyhauled me in on it at two this morning. You know how many noses you’ve got out of joint, Lieutenant? And what the level of concern is about that mess out there on the front?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“I’m sure you hoped for a commendation and maybe better, wouldn’t that be it? Wouldn’t blame you. Well, I got my hands into this, and I’ve opted you under my orders, Lieutenant, because I can do that and high command’s just real worried the Bureau’s going to poke and prod and that elf’s going to leave us on the sudden for elvish heaven. So let’s just keep him moderately happy. He wants to talk to you. What the Bureau wants to tell you, but I told them I’dmake it clear, because they’ll talk tech at you and I want to be sure you’ve got it—it’s just real simple: you’re dealing with an alien; and you’ll have noticed what he says doesn’t always make sense.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Don’t yes ma’am me, Lieutenant, dammit; just talk to me and look me in the eye. We’re talking about communication here.”

“Yes—” He stopped short of the ma’am.

“You’ve got a brain, deFranco, it’s all in your record. You almost went Special Services yourself, that was your real ambition, wasn’t it? But you had this damn psychotic fear of taking ultimate responsibility. And a wholesome fear of ending up with a commendation, posthumous. Didn’t you? It washed you out, so you went special ops where you could take orders from someone else and still play bloody hero and prove something to yourself—am I right? I ought to be; I’ve got your psych record over there. Now I’ve insulted you and you’re sitting there turning red. But I want to know what I’m dealing with. We’re in a damn bind. We’ve got casualties happening out there. Are you and I going to have trouble?”

“No. I understand.”

“Good. Very good. Do you think you can go into a room with that elf and talk the truth out of him? More to the point, can you make a decision, can you go in there knowing how much is riding on your back?”

“I’m not a—”

“I don’t care what you are, deFranco. What I want to know is whether negotiateis even in that elf’s vocabulary. I’m assigning you to guard over there. In the process I want you to sit down with him one to one and just talk away. That’s all you’ve got to do. And because of your background maybe you’ll do it with some sense. But maybe if you just talk for John deFranco and try to get that elf to deal, that’s the best thing. You know when a government sends out a negotiator—or anything like—that individual’s not average. That individual’s probably the smartest, canniest, hardest-nosed bastard they’ve got, and he probably cheats at dice. We don’t know what this bastard’s up to or what he thinks like, and when you sit down with him, you’re talking to a mind that knows a lot more about humanity than we know about elves. You’re talking to an elvish expert who’s here playing games with us. Who’s giving us a real good look-over. You understand that? What do you say about it?”

“I’m scared of this.”

“That’s real good. You know we’re not sending in the brightest, most experienced human on two feet. And that’s exactly what that rather canny elf has arranged for us to do. You understand that?

He’s playing us like a keyboard this far. And how do you cope with that, Lieutenant deFranco?”

“I just ask him questions and answer as little as I can.”

“Wrong. You let him talk. You be real carefulwhat you ask him.

What you ask is as dead a giveaway as what you tell him.

Everything you do and say is cultural. If he’s good, he’ll drain you like a sponge.” The colonel bit her lips. “Damn, you’re notgoing to be able to handle that, are you?”

“I understand what you’re warning me about, Colonel. I’m not sure I can do it, but I’ll try.”

“Not sure you can do it. Peacemay hang on this. And several billion lives. Your company, out there on the line. Put it on that level. And you’re scared and you’re showing it, Lieutenant; you’re too damned open, no wonder they washed you out. Got no hard center to you, no place to go to when I embarrass the hell out of you, and I’mon your side. You’re probably a damn good special op, brave as hell, I know, you’ve got commendations in the field. And that shell-shyness of yours probably makes you drive real hard when you’re in trouble. Good man. Honest. If the elf wants a human specimen, we could do worse. You just go in there, son, and you talk to him and you be your nice self, and that’s all you’ve got to do.”

“We’ll be bugged.” DeFranco stared at the colonel deliberately, trying to dredge up some self-defense, give the impression he was no complete fool.

“Damn sure you’ll be bugged. Guards right outside if you want them. But if you startle that elf I’ll fry you.”

“That isn’t what I meant. I meant—I meant if I could get him to talk there’d be an accurate record.”

“Ah. Well. Yes. There will be, absolutely. And yes, I’m a bastard, Lieutenant, same as that elf is, beyond a doubt. And because I’m on your side I want you as prepared as I can get you. But I’m going to give you all the backing you need—you want anything, you just tell that staff and they better jump to do it. I’m giving you carte blanche over there in the Science Wing. Their complaints can come to this desk. You just be yourself with him, watch yourself a little, don’t get taken and don’t set him off.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Another slow, consuming stare and a nod.

He was dismissed.

IV

So where’s the hole we’re digging end?

Why, it’s neverneverdone, my friend.

Well, why’s it warm at the other end?

Well, hell’s neverneverfar, my friend.

“This colonel,” says the elf, “it’s her soldiers outside.”

“That’s the one,” says deFranco.

“It’s not the highest rank.”

“No. It’s not. Not even on this world.” DeFranco’s hands open and close on each other, white-knuckled. His voice stays calm. “But it’s a lot of power. She won’t be alone. There are others she’s acting for.

They sent me here. I’ve figured that now.”

“Your dealing confuses me.”

“Politics. It’s all politics. Higher-ups covering their—” DeFranco rechooses his words. “Some things they have to abide by. They have to do. Like if they don’t take a peace offer—that would be trouble back home. Human space is big. But a war—humans want it stopped. I know that. With humans, you can’t quiet a mistake down. We’ve got too many separate interests… We got scientists, and a half dozen different commands—”

“Will they all stop fighting?”

“Yes. My side will. I know they will.” DeFranco clenches his hands tighter as if the chill has gotten to his bones. “If we can give them something, some solution. You have to understand what they’re thinking of. If there’s a trouble anywhere, it can grow.

There might be others out there, you ever think of that? What if some other species just—wanders through? It’s happened. And what if our little war disturbs them? We live in a big house, you know that yet? You’re young, you, with your ships, you’re a young power out in space. God help us, we’ve made mistakes, but this time the first one wasn’t ours. We’ve been trying to stop this. All along, we’ve been trying to stop this.“

“You’re what I trust,” says the elf. “Not your colonel. Not your treaty words. Not your peace. You. Words aren’t the belief. What you do—that’s the belief. What you do will show us.”

“I can’t!”

“I can. It’s important enough to me and not to you. Our little war

. I can’t understand how you think that way.”

“Look at that!” DeFranco waves a desperate hand at the room, the world. Up. “It’s so big! Can’t you see that? And one planet, one ball of rock. It’s a little war. Is it worth it all? Is it worth such damn stubbornness? Is it worth dying in?”

“Yes,” the elf says simply, and the sea-green eyes and the white face have neither anger nor blame for him.

DeFranco saluted and got out and waited until the colonel’s orderly caught him in the hall and gave his escort the necessary authorizations, because no onewandered this base without an escort. (But the elves are two hundred klicks out there, deFranco thought; and who’re we fighting anyway?) In the halls he saw the black of Union elite and the blue of Alliance spacers and the plain drab of the line troop officers, and the white and pale blue of the two Science Bureaus; while everywhere he felt the tenuous peace—damn, maybe we needthis war, it’s keeping humanity talking to each other, they’re all fat and sleek and mud never touched them back here– But there was haste in the hallways. But there were tense looks on faces of people headed purposefully to one place and the other, the look of a place with something on its collective mind, with silent, secret emergencies passing about him– The attack on the lines, he thought, and remembered another time that attack had started on one front and spread rapidly to a dozen; and missiles had gone. And towns had died.

And the elvish kids, the babies in each others’ arms and the birds fluttering down; and Dibs—Dibs lying in his armor like a broken piece of machinery—when a shot got you, it got the visor and you had no face and never knew it; or it got the joints and you bled to death trapped in the failed shell, you just lay there and bled: he had heard men and women die like that, still in contact on the com, talking to their buddies and going out alone, alone in that damn armor that cut off the sky and the air–

They brought him down tunnels that were poured and cast and hard overnight, thatkind of construction, which they never got out on the Line. There were bright lights and there were dry floors for the fine officers to walk on; there was, at the end, a new set of doors where guards stood with weapons ready—

–against us? DeFranco got that sense of unreality again, blinked as he had to show his tags and IDs to get past even with the colonel’s orders directing his escort.

Then they let him through, and further, to another hall with more guards. AlSec MPs. Alliance Security. The intelligence and Special Services. The very air here had a chill about it, with only those uniforms in sight. Theyhad the elf. Of course they did. He was diplomatic property and the regs and the generals had nothing to do with it. He was in Finn’s territory. Security and the Surface Tactical command, that the reg command only controlled from the top, not inside the structure. Finn had a leash, but she took no orders from sideways in the structure. Not even from AlSec. Check and balance in a joint command structure too many light-years from home to risk petty dictatorships. He had just crossed a line and might as well have been on another planet.

And evidently a call had come ahead of him, because there were surly Science Bureau types here too, and the one who passed him through hardly glanced at his ID. It was his face the man looked at, long and hard; and it was the Xenbureau interviewer who had been on the tape.

“Good luck,” the man said. And a SurTac major arrived, dour-faced, a black man in the SurTac’s khaki, who did not look like an office-type. Hetook the folder of authorizations and looked at it and at deFranco with a dark-eyed stare and a set of a square, well-muscled jaw. “Colonel’s given you three hours, Lieutenant. Use it.”

“We’re more than one government,” says deFranco to the elf, quietly, desperately. “We’ve fought in the past. We had wars. We made peace and we work together. We may fight again but everyone hopes not and it’s less and less likely. War’s expensive. It’s too damn open out here, that’s what I’m trying to tell you. You start a war and you don’t know what else might be listening.” The elf leans back in his chair, one arm on the back of it. His face is solemn as ever as he looks at deFranco. “You and I, you-and-I.

The world was whole until you found us. How can people do things that don’t make sense? The wholething makes sense, the parts of the thing are crazy. You can’t put part of one thing into another, leaves won’t be feathers, and your mind can’t be our mind. I see our mistakes. I want to take them away. Then elves won’t have theirs and you won’t have yours. But you call it a little war. The lives are only a few. You have so many. You like your mistake. You’ll keep it.

You’ll hold it in your arms. And you’ll meet these others with it. But they’ll see it, won’t they, when they look at you?”

“It’s crazy!”

“When we met you in it, we assumed we. That was our first great mistake. But it’s yours too.”

DeFranco walked into the room where they kept the elf, a luxurious room, a groundling civ’s kind of room, with a bed and a table and two chairs, and some kind of green and yellow pattern on the bedclothes, which were ground-style, free-hanging. And amid this riot of life-colors the elf sat cross-legged on the bed, placid, not caring that the door opened or someone came in—until a flicker of recognition seemed to take hold and grow. It was the first humanlike expression, virtually the only expression, the elf had ever used in deFranco’s sight. Of course there were cameras recording it, recording everything. The colonel had said so and probably the elf knew it too.

“Saitas. You wanted to see me.”

“DeFranco.” The elf’s face settled again to inscrutability.

“Shall I sit down?”

There was no answer. DeFranco waited for an uncertain moment, then settled into one chair at the table and leaned his elbows on the white plastic surface.

“They treating you all right?” deFranco asked, for the cameras, deliberately, for the colonel– (Damn you, I’m not a fool, I can play your damn game, Colonel, I did what your SurTacs failed at, didn’t I? So watch me.)

“Yes,” the elf said. His hands rested loosely in his red-robed lap.

He looked down at them and up again.

“I tried to treat you all right. I thought I did.”

“Yes.”

“Why’d you ask for me?”

“I’m a soldier,” the elf said, and put his legs over the side of the bed and stood up. “I know that you are. I think you understand me more.”

“I don’t know about that. But I’ll listen.” The thought crossed his mind of being held hostage, of some irrational violent behavior, but he pretended it away and waved a hand at the other chair. “You want to sit down? You want something to drink? They’ll get it for you.”

“I’ll sit with you.” The elf came and took the other chair, and leaned his elbows on the table. The bruises on his wrists showed plainly under the light. “I thought you might have gone back to the front by now.”

“They give me a little time. I mean, there’s—” (Don’t talk to him, the colonel had said. Let him talk.)

“—three hours. A while. You had a reason you wanted to see me.

Something you wanted? Or just to talk. I’ll do that too.”

“Yes,” the elf said slowly, in his lilting lisp. And gazed at him with sea-green eyes. “Are you young, deFranco? You make me think of a young man.”

It set him off his balance. “I’m not all that young.”

“I have a son and a daughter. Have you?”

“No.”

“Parents?”

“Why do you want to know?”

“Have you parents?”

“A mother. Long way from here.” He resented the questioning.

Letters were all Nadya deFranco got, and not enough of them, and thank God she had closer sons. DeFranco sat staring at the elf who had gotten past his guard in two quick questions and managed to hit a sore spot; and he remembered what Finn had warned him.

“You, elf?”

“Living parents. Yes. A lot of relatives?” Damn, what trooper had they stripped getting that part of human language? Whose soul had they gotten into?

“What are you, Saitas? Why’d they hand you over like that?”

“To make peace. So the Saitas always does.”

“Tied up like that?”

“I came to be your prisoner. You understand that.”

“Well, it worked. I might have shot you; I don’t say I would’ve, but I might, except for that. It was a smart move, I guess it was.

But hell, you could have called ahead. You come up on us in the dark—you looked to get your head blown off. Why didn’t you use the radio?”

A blink of sea-green eyes. “Others ask me that. Would you have come then?”

“Well, someone would. Listen, you speak at them in human language and they’d listen and they’d arrange something a lot safer.”

The elf stared, full of his own obscurities.

“Come on, they throw you out of there? They your enemies?”

“Who?”

“The ones who left you out there on the hill.”

“No.”

“Friends, huh? Friendslet you out there?”

“They agreed with me. I agreed to be there. I was most afraid you’d shoot them. But you let them go.”

“Hell, look, I just follow orders.”

“And orders led you to let them go?”

“No. They say to talk if I ever got the chance. Look, me, personally, I never wanted to kill you guys. I wouldn’t, if I had the choice.”

“But you do.”

“Dammit, you took out our ships. Maybe that wasn’t personal on your side either, but we sure as hell can’t have you doing it as a habit. All you ever damn well had to do was go away and let us alone. You hit a world, elf. Maybe not much of one, but you killed more than a thousand people on that first ship. Thirty thousand at that base, good God, don’t sit there looking at me like that!”

“It was a mistake.”

“Mistake.” DeFranco found his hands shaking. No. Don’t raise the voice. Don’t lose it. (Be your own nice self, boy. Patronizingly.

The colonel knew he was far out of his depth. And he knew.) “Aren’t most wars mistakes?”

“Do you think so?”

“If it is, can’t we stop it?” He felt the attention of unseen listeners, diplomats, scientists—himself, special ops, talking to an elvish negotiator and making a mess of it all, losing everything. (Be your own nice self– The colonel was crazy, the elf was, the war and the world were and he lumbered ahead desperately, attempting subtlety, attempting a caricatured simplicity toward a diplomat and knowing the one as transparent as the other.) “You know all you have to do is say quit and there’s ways to stop the shooting right off, ways to close it all down and then start talking about how we settle this. You say that’s what you came to do. You’re in the right place. All you have to do is get your side to stop. They’re killing each other out there, do you know that? You come in here to talk peace. And they’re coming at us all up and down the front. I just got word I lost a friend of mine out there. God knows what by now. It’s no damn sense. If you can stop it, then let’s stop it.”

“I’ll tell you what our peace will be.” The elf lifted his face placidly, spread his hands. “There is a camera, isn’t there? At least a microphone. They do listen.”

“Yes. They’ve got camera and mike. I know they will.”

“But your face is what I see. Your face is all human faces to me.

They can listen, but I talk to you. Only to you. And this is our peace. The fighting will stop, and we’ll build ships again and we’ll go into space, and we won’t be enemies. The mistake won’t exist.

That’s the peace I want.”

“So how do we do that?” (Be your own nice self, boy– DeFranco abandoned himself. Don’t see the skin, don’t see the face alien-like, just talk, talk like to a human, don’t worry about protocols. Doit, boy.) “How do we get the fighting stopped?”

“I’ve said it. They’ve heard.”

“Yes. They have.”

“They have two days to make this peace.”

DeFranco’s palms sweated. He clenched his hands on the chair.

“Then what happens?”

“I’ll die. The war will go on.”

(God, now what do I do, what do I say? How far can I go?)

“Listen, you don’t understand how long it takes us to make up our minds. We need more than any two days. They’re dying out there, your people are killing themselves against our lines, and it’s all for nothing. Stop it now. Talk to them. Tell them we’re going to talk.

Shut it down.”

The slitted eyes blinked, remained in their buddha-like abstraction, looking askance into infinity. “DeFranco, there has to be payment.”

(Think, deFranco, think. Ask the right things.)

“What payment? Just exactly who are you talking for? All of you?

A city? A district?”

“One peace will be enough for you—won’t it? You’ll go away.

You’ll leave and we won’t see each other until we’ve built our ships again. You’ll begin to go—as soon as my peace is done.”

“Build the ships, for God’s sake. And come after us again?”

“No. The war is a mistake. There won’t be another war. This is enough.”

“But would everyone agree?”

“Everyone does agree. I’ll tell you my real name. It’s Angan.

Angan Anassidi. I’m forty-one years old. I have a son named Agaita; a daughter named Siadi; I was born in a town named Daogisshi, but it’s burned now. My wife is Llaothai Sohail, and she was born in the city where we live now. I’m my wife’s only husband. My son is aged twelve, my daughter is nine. They live in the city with my wife alone now and her parents and mine.” The elvish voice acquired a subtle music on the names that lingered to obscure his other speech. “I’ve written—I told them I would write everything for them. I write in your language.”

“Told who?”

“The humans who asked me. I wrote it all.” DeFranco stared at the elf, at a face immaculate and distant as a statue. “I don’t think I follow you. I don’t understand. We’re talking about the front. We’re talking about maybe that wife and those kids being in danger, aren’t we? About maybe my friends getting killed out there. About shells falling and people getting blown up. Can we do anything about it?”

“I’m here to make the peace. Saitas is what I am. A gift to you.

I’m the payment.”

DeFranco blinked and shook his head. “Payment? I’m not sure I follow that.”

For a long moment there was quiet. “Kill me,” the elf said.

“That’s why I came. To be the last dead. The saitas. To carry the mistake away.”

“Hell, no. No. We don’t shoot you. Look, elf—all we want is to stop the fighting. We don’t want your life. Nobody wants to kill you.”

“DeFranco, we haven’t any more resources. We want a peace.”

“So do we. Look, we just make a treaty—you understand treaty?”

“I’m the treaty.”

“A treaty, man, a treaty’s a piece of paper. We promise peace to each other and not to attack us, we promise not to attack you, we settle our borders, and you just go home to that wife and kids. And I go home and that’s it. No more dying. No more killing.”

“No.” The elf’s eyes glistened within the pale mask. “No, deFranco, no paper.”

“We make peace with a paper and ink. We write peace out and we make agreements and it’s good enough; we do what we say we’ll do.”

“Then write it in your language.”

“You have to sign it. Write your name on it. And keep the terms.

That’s all, you understand that?”

“Two days. I’ll sign your paper. I’ll make your peace. It’s nothing.

Our peace is in me. And I’m here to give it.”

“Dammit, we don’t kill people for treaties.” The sea-colored eyes blinked. “Is one so hard and millions so easy?”

“It’s different.”

“Why?”

“Because—because—look, war’s for killing; peace is for staying alive.”

“I don’t understand why you fight. Nothing you do makes sense to us. But I think we almost understand. We talk to each other. We use the same words. DeFranco, don’t go on killing us.”

“Just you. Just you, is that it? Dammit, that’s crazy!”

“A cup would do. Or a gun. Whatever you like. DeFranco, have you never shot us before?”

“God, it’s not the same!”

“You say paper’s enough for you. That paper will take away all your mistakes and make the peace. But paper’s not enough for us.