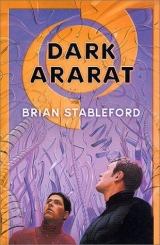

Текст книги "Dark Ararat"

Автор книги: Brian Stableford

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

FOUR

The smartsuits Matthew and Solari were given to wear while their surface suits were being tailored were very similar to the ones they’d worn in the months before being frozen down, and not much different from the ones Matthew had worn on Earth—he’d never been a follower of fashion or a devotee of exotic display. They were, however, conspicuously unlike the white exterior presented by Nita Brownell or the pale blue-gray one manifested by Frans Leitz, which were presumably the “specialized ship suits” they weren’t being given. The main color of the smartsuits was modifiable, but only from dark blue to black and back again, and such style as they possessed was similarly restricted. Matthew guessed that if he and Solari were to go a-wandering they would stick out like sore thumbs in any line of sight they happened to cross.

The doctor told them that they’d get their personal possessions back “in due course.”

By the time that he and Solari finally got to eat an authentic meal, in the middle of the second day of their new life, Matthew was expecting a veritable orgy of sensual delights. He was disappointed; the flavors were too bland for his taste, the textures too meltingly soft and the net effect slightly nauseating. The doctor and her assistant had left them to it, so they had no one to complain to but one another.

“It is the food, or us?” Solari asked.

“Mainly us, I think,” Matthew told him. “Our expectations were probably too high. Until our stomachs are back to normal they’ll be sending out queasiness signals. On the other hand, the crew have had seven hundred years of cultural isolation, so their tastes have probably changed quite markedly.”

“Have to wait till we get to the surface, then,” Solari said, philosophically. “At least they’ll have had three years practice growing Earthly crops.”

“I don’t suppose it’ll be a great deal better,” Matthew said, “given that their staples will be whole-diet wheat-and rice-mannas. If we’re lucky, though, these gutskins they’re going to extend from our lips to our arseholes via our intestinal labyrinths will enhance taste sensations rather than muffling them, and nausea will be out of the question.”

“I’m beginning to get a sense of how long I’ve been away,” Solari mused. “The fitter I get, the more obvious the differences become. Bound to happen, of course.”

“It was always going to be a wrench,” Matthew agreed. “But things are definitely more awkward than we could have wished. I suppose we have to be patient, with ourselves as well as our careful hosts. We’ll rediscover all the pleasures, given time—and we’ll probably find that the keyboards attached to those hoods and display screens are a lot more user-friendly than they seem at first glance. Seven hundred years of progress can’t have obliterated the underlying logic. Once we get used to them, we’ll presumably have access to the ship’s data banks—and then we can catch up with allthe news, good and bad alike.”

Solari looked over his shoulder at the consoles behind his bedhead, then up at the hoods and dangling keyboards. He pulled down a hood and fitted it over his head and eyes, but had to lift it up again to reach for a keyboard.

Now that the two of them were free to sit up in their beds, or even reconfigure the beds as chairs, it was easy enough to bring down the hoods over their heads or activate wraparound screens, and use any of half a dozen touchpads. Unfortunately, no one had taken the trouble as yet to brief them on the use of the controls. In theory, everything they might want to know was probably at their fingertips, but Hope’s crew seemed to be in no hurry to educate their fingertips in their art of searching.

“We could probably figure them out, given time,” Solari said, as he pushed the hood back up again. “But will we have the time? They seem keen to send us down to the surface beforewe can figure out exactly what’s going on up here. There’s a hell of a lot to be learned and we’ve been thrown in at the deep end. The colony’s first bases are already in place, if not exactly up and running—although the endeavor’s obviously made enough progress to produce its first major crime.”

“Its first unsolvedmajor crime,” Matthew said. “The first, at any rate, that has proved so awkwardly problematic as to provoke demands for an investigation by fresh and practiced eyes—and a replacement for the victim. Thrown in at the deep endis probably an understatement.”

Solari had decided that he had had enough to eat some time before Matthew finally decided to give up. The detective had pushed his plate away in order to begin playing with the overhead apparatus, but he gave up on that now in favor of more adventurous action. He took one last swig of water before swinging his legs over the side of the bed and dropping lightly to the floor. Once he had tested the strength of his limbs he went to the door of the room and pressed the release-pad.

The door slid open immediately, affording Matthew some slight reassurance, although he knew that it wasn’t actually necessary to lock a door in order to secure a prison.

When Solari stepped out into the corridor the door slid shut behind him, cutting off the sound of his voice as soon as he had begun to speak.

Matthew shoved his own food away and took a last sip of water before stepping down from his own bed. He looked speculatively at the door, but there was a certain luxury in being alone for the first time since his emergence from SusAn, so he took time out to dispose of the degradable plates and utensils they had employed.

By the time he had finished clearing up the door had opened again and Solari was coming back into the room.

The policeman came to stand very close to him and spoke in a confidential whisper, although he must have known that lowering his voice was unlikely to be enough to prevent his being overheard.

“There’s a man standing guard outside,” he said. “He says his name’s Riddell. Same uniform as the boy—except for the sidearm. Same feet too. He says he’ll be only too glad to take one or both of us anywhere we might want to go, when we’re well enough.”

“What kind of sidearm?” Matthew wanted to know.

“Looks like a darter. Probably non-lethal, but that’s not the point.”

It certainly wasn’t, Matthew thought. No matter how quick the man outside their door had been to reassure Solari that he wasn’t there to keep them prisoner, his armed presence spoke volumes. What it said, first and foremost, was that there were people on the ship who might want to talk to the newly awakened, and might have to be actively deterred from so doing. Who? And why were the captain’s men determined to stop them? Matthew looked at the hoods and keyboards, then at the wallscreens. Even if there was no broadcast TV on Hope, there had to be a telephone facility. Either no one had attempted to call them, or their calls had not been put through. Was that why their personal belongings, including their beltphones, had not yet been returned to them?

“Seven hundred years of progress,” Matthew said, keeping his own voice low even though he knew as well as well as Solari did how futile the gesture was, “and even Hopeis home to armed men. For all we know, there’s a full-scale civil war in progress. If Shen Chin Che were dead, he’d be spinning in his grave. If he’s not …”

He wanted to follow that train of thought further, but Solari was keeping a tighter focus on the matter in hand. “Whoever killed Delgado on the surface may have friends up here,” the policeman observed. “Mr. Riddell might be there to protect us.” He didn’t sound as if he believed it.

“We were all supposed to be on the same side,” Matthew went on, angling the trajectory of his conversation very slightly to take aboard Solari’s comment. “Crew and human cargo, scientists and colonists, all working together in the same great scheme. The whole point of building the Ark was to leave behind the divisions and the stresses that were standing in the way of saving Earth. We were all supposed to be united in a common cause, having put the past behind us. How could that go badly wrong in three short years?”

“And seven hundred long ones,” Solari reminded him.

“Are we being too paranoid, do you think?” Matthew asked.

Solari didn’t have time to answer that one before Frans Leitz came back in. “The captain will see you both at eight-zero,” the boy said. “He apologizes for not having been there to greet you when Dr. Brownell brought you out of the induced coma for the last time, but he’s very busy.”

Matthew realized that he had no idea what the present time was, and couldn’t be sure what eight-zero might signify. There was no clock on the wall of the room, and he remembered now that Nita Brownell had said something odd about fifty hours being the equivalent of five days of “old time.”

When he asked for an explanation, Leitz explained to him that the ship operated on metric time, using an Earth-day as a base because it suited the Circadian rhythms built into crew physiology. Each day was divided up into ten hours of a hundred minutes, which were further subdivided into a hundred seconds. Surface time had kept the same basic structure, but had adopted the local day as a base, thus resulting in a desynchronization of ship and surface time. The local day, determined by the planet’s rotation, was 0.89 of a ship day.

“We think that’s another of the reasons for the groundlings’ continuing unease,” Leitz told them. “It’s proved to be surprisingly difficult to modify the physiology of Circadian rhythms, but we’re sure that they’ll solve the problem soon. If only they could be patient … anyhow, the planet’s year is one point twenty-eight Earth-standard, but its axial tilt is very slight, so its temperate-zone seasons aren’t nearly as extreme. That’s not problematic, although Professor Lityansky thinks it has something to do with the strange pattern of local evolution. He’ll explain it when he briefs you tomorrow, Professor Fleury. That’s at three-zero, provided that you’re up to it. How do you feel now?”

“Better,” Matthew assured him, drily. “Professor Lityansky’s busy too, I dare say.”

“Extremely busy,” the boy replied. “He’s working flat-out trying to figure out exactly what we need to do to make the colony work. He’s under a great deal of pressure, because the groundlings hold him primarily responsible for the decision that the world is sufficiently Earthlike to qualify as a clone. The decision to go ahead with the colonization wasn’t entirely his, of course, but his genomic analyses provided the relevant data and his judgment of their significance was crucial. He feels badly let down by some of the people on the surface.”

“How come their judgment is so different?” Matthew asked.

Leitz hesitated, but eventually decided to answer the question. He was becoming more relaxed now, and a certain boyish enthusiasm was beginning to show through. “Our data was limited, of course,” the youth conceded. “Our nanotech is way behind Earth’s, and we haven’t been able to improve our probes to anything like the same degree while we’ve been in transit. Apart from evidence gathered at long-range by our instruments, we had a very limited range of surface-gathered samples to work from. They were adequate for genomic analysis, but most of what we had on which to base our decision was fundamental biochemical data. The photographs taken by our flying eyes showed us what the local plant life looked like, but we didn’t have any real notion of the ecology of the world, or even of its diversity, let alone its evolutionary history. Once the first landing was complete, the biologists on the ground began to fill in the other parts of the picture—and they began to get alarmed.

“Some of the groundlings began to argue that Professor Lityansky had made a bad mistake, because he hadn’t been able to think through the consequences of his genomic analyses. The extreme view is that the colonization should have been put on hold as soon as it was realized that the local ecosphere wasn’t DNA-based—but that’s absurd, isn’t it, Professor Fleury?”

Matthew could see what the young man was getting at. When Hopehad set out from the solar system its scientists had not the slightest idea exactly how alien any alien life they discovered might turn out to be. Having only had a single ecosphere on which to base their expectations, they had no way to arbitrate between hypotheses that held that life throughout the universe was likely to be DNA-based, or that DNA would turn out to be a strictly local phenomenon unrepeated anywhere else.

Matthew had always had more sympathy for the former opinion, not because he lent any credence to the panspermist myth—which held that life had originated elsewhere and arrived on Earth while being dispersed throughout the expanding cosmos—but because it seemed to him that natural selection operating in the struggle for existence in the primordial sludge would probably have found the same optimum solution to the business of genetic coding that would materialize elsewhere. In the absence of any comparative cases, however, the matter had been pure guesswork—until Frans Leitz’s forbears had found the “sludgeworld” whose bacteria employed a different molecule.

Armed with that foreknowledge, Lityansky and his fellows would have been less surprised than their newly defrosted colleagues to find that the new world’s ecosphere also had a different coding-molecule. Indeed, Professor Lityansky might well have taken that as good evidence that DNA wasa purely local phenomenon, unlikely to be repeated anywhere in the universe—given which, any would-be colonists of new worlds would simply have to take it as given that they could not expect to find conditions entirely to their liking.

“I wouldn’t call it absurd,” was what Matthew was prepared to say to Leitz at this stage. “People had argued about what might or might not qualify as an Earth-clone world long before Hopewas a gleam in Shen Chin Che’s eye. It wouldn’t have been regarded as an extreme view to say that an ecosphere had to be DNA-based to qualify as a clone. On the other hand, we didn’t set out with the proviso that we had to find DNA in order to found a colony. We set out with the intention of making the best of whatever we could find.”

“Exactly,” said Leitz. “And that’s what we have to do. The fact that Earth came through its own ecocatastrophe doesn’t make any difference to our quest; there was never any question of going back. And the fact that the other probes sent out in this general direction haven’t located any other world that’s even remotely Earth-like means that we simply can’tpass up this chance. Isn’t that so?”

“I can’t answer that until I have more facts at my disposal,” Matthew said, “But aren’t you avoiding the most important issue of all? If this world is inhabited …”

“It isn’t,” Leitz was quick to say. “It was, but it’s not now. The colony had been active for more than a year before the so-called city was found. It was overgrown to such an extent that it was virtually invisible from the air. Nothing else has shown up, in spite of increased probe activity. The people at Base Three found not the slightest evidence of recent habitation, until …” He stopped.

“Until Bernal was murdered,” Matthew finished for him.

“By one of his colleagues,” Leitz said, stubbornly. “The killer may have used a weapon tricked up to look like a local product, but it musthave been a human hand that wielded it. The people at Base Three seem to be determined not to carry out a full and proper investigation of their own, so we had no choice but to wake Inspector Solari.”

Matthew was still puzzled. “Are you implying that the people Bernal was working with are running some kind of scam?” he asked. “You think they’re pretendingthat he was killed by aliens? Why?”

Leitz’s discomfort deepened yet again. “I don’t know,” he said, defensively. “But there are certainly people at Base One who’ve added the possible continued existence of the aborigines—however unlikely the possibility may be—to the list of reasons why Professor Lityansky should never have initiated the landings. The people who want to withdraw from the planet are desperate for any justification they can find.”

“So why not let the ones who want out withdraw? Wouldn’t it be better to have a colony of committed volunteers than one whose members are fighting among themselves?” Matthew thought that he already knew the answer to that one, but he wanted to see Leitz’s response.

It was, as he’d anticipated, almost explosive. “But that’s the one thing we can’tdo!” the youth exclaimed. “If the colony is to be viable, it will eventually need the full repertoire of the skills possessed by the cargo—and even if one member of each notional pair decided to stay, that would still leave the colony with a dangerously depleted gene pool. It’s absolutely vital that they allaccept the necessity of making the colony work. You must see that, Professor Fleury. You must.”

Must I?Matthew thought.

Vince Solari’s interest in genomics was limited, and he obviously wanted to get back to more immediate concerns. Matthew’s reluctance to endorse Leitz’s categorical imperative gave him the opportunity to butt in. “Why is the guard in the corridor wearing a gun, Mr. Leitz?” he asked, bluntly. “In fact, why should anyoneaboard the ship be wearing a gun?”

Frans Leitz colored, but the greenish tint in his skin lent the blush a peculiar dullness. “It’s purely a precaution,” he said.

“I figured that,” Solari came back. “What I want to know is: against what?”

“There have been … policy disagreements concerning the administration of the ship and the control of its resources,” the boy admitted. “I’m really not competent to explain the details—I’m just a medical orderly, and a trainee at that. The captain will tell you everything. But it really is a precaution. No one on the ship has been injured, let alone killed, as a result of the … problem.”

“But who, exactly, is the precaution intended to deter?” Mathew said, modifying Solari’s question slightly without softening the insistence of the demand. “Are we talking about mutineers, or what?”

“I suppose so,” the boy replied, steadfastly refusing to elaborate—but he must have read in Vince Solari’s eyes that he wouldn’t be let off so easily. “The captain will tell you all that. He can explain it far better.”

“I’m sure he can,” Matthew said, drily, “but …”

Frans Leitz had had enough. “Eight-zero,” the boy said, as he turned to flee from the uncomfortable field of discussion. “Before you go,” Solari was quick to say, “can you give us a quick introduction to the equipment by our beds. There’s so much we need to know that the sooner we can make a start ourselves the better equipped we’ll be to ask questions of the captain.”

Leitz hesitated, but he had no grounds for refusal—and he knew that if he were busy lecturing the two of them on basic equipment skills he could probably override more awkward questions with ease.

“Sure,” he said, only a little less warmly than Matthew could have wished.

FIVE

When the first picture of the new world came up on the wallscreen Matthew caught his breath. He had thought himself more than ready for it, but the reality still took him by surprise.

The image reminded him, as he had expected, of the classic twentieth-century images of the Earth as seen from the moon, but the differences leapt out at him much more assertively than he had imagined. The new world’s two moons were much smaller and closer than Earth’s, and they were both in the picture, which had obviously been synthesized from photographs taken from Hopewhile she was much further away than her present orbit.

The second thing Matthew noticed, after absorbing the shock of the two moons, was the similarity of the clouds. It was as if his mind were making a grab for something reassuring, and that it was able to take some comfort from the notion that the old Earth and the new were clad in identical tattered white shirts.

But everything else was different.

The land masses were, of course, completely different in shape, but that was a trivial matter. The strikingdifference was a matter of color. Matthew, having been forewarned, was expecting to see purple, but he had somehow taken it for granted that it would be the land rather than the sea that would be imperial purple, and it took him a moment or two to reverse his first impression.

Even at its most intense, the purple of this world’s land-based vegetation was paler than he had expected. It seemed somehow insulting to think in terms of mauveor lilac, although those shades were certainly the most common. So vague and careless had Matthew’s anticipations been that he had not factored in the oceans in at all, and would not have been at all surprised to find them as blue as Earth’s. They were not; they were gloriously and triumphantly purple, more richly and stridently purple than the land.

Matthew remembered that the first aniline dye to be synthesized from coal tar in Earth’s nineteenth century had been dubbed Tyrian purple. That, presumably, was why Tyre had been added to the list of potential names for “the world.” The murex, he supposed, must have been the source of the imperial purple of Rome, and there were probably mollusk-like creatures of a similar sort in the purple oceans of the new world, but Murex did not sound quite right to Matthew as the name of a world. Tyre and Ararat seemed somehow far more fitting.

Matthew might have paused for a while to wonder whether the oceans were so richly purple because they were abundantly populated by photosynthetic microorganisms and algae, or because of some unexpected trick of atmospheric refraction, but his companion had the keyboard and Solari was already racing ahead in search of more various, more intimate, and more detailed views, while Frans Leitz looked on approvingly. The former hypothesis, Matthew decided en passant, seemed more likely as well as more attractive—but so had the hypothesis that DNA would always be selected out by the struggle to produce true life from mere organic mire.

“Can you find a commentary?” Matthew asked.

Solari shook his head. “None available. I guess they haven’t had time to add the voiceovers yet.” He glanced at Leitz as he spoke.

“We didn’t think a commentary was required,” the crewman said.

Other surprises followed as the mute viewpoint moved a little closer to the surface. Matthew had not been expecting the desert areas to be so silvery, or the ice caps so neatly star-shaped. He saw both ice caps as the synthesized image rotated about two axes, always presenting a full disk to the AI-eye.

“The symmetry of the continents is a little weird,” Leitz put in, obviously feeling some slight obligation to substitute for the missing commentary. “The polar island-continents are so similar in size and shape that some of the first observers thought that the planet had been landscaped by continental engineers. The star is nearly a billion years older than the sun, so evolution has had a lot longer to work here than it had on Earth, but Professor Lityansky reckons that the relative lack of axial tilt and tidal drag haven’t added sufficient agitation to the surface conditions to move evolution along at a similar pace. He reckons that Earth was unusually lucky in that respect, and that’s why we seem to be the first starfaring intelligences in this part of the galaxy. The surface isn’t very active, volcanically speaking, and the climatic regimes are stable. The weather’s fairly predictable in all latitudes, although it varies quite sharply from one part of the pattern to another.”

The viewpoint was zooming in now, as if free-falling from orbit, then curving gracefully into a horizontal course a thousand meters or so above the surface.

The sky was bluish, but it had a distinct violet tinge, like an eerie echo of the vegetation.

At first, Matthew thought that the grassy plain over which the AI-eye was soaring wasn’t so very different from an Earthly prairie. The lack of any comparative yardstick made it difficult to adjust the supposition, but when Leitz told him that the stalks bearing the complex crowns were between ten and twenty meters tall he tried to get things into a clearer perspective.

“The rigid parts of the plants aren’t like wood at all,” Leitz said. “More like glass. Professor Lityansky will explain the biochemistry.”

There were very few tree-like forms on the plain, but when the point of view soared higher in order to pass over a mountain range, Matthew saw whole forests of structures that seemed to have as much in common with corals as with oaks or pines. They seemed to him to be the kind of trees that a nineteenth-century engineer—a steam-and-steel man—might have devised to suit a landscape whose primary features were mills and railroads: trees compounded out of pipes and wire, scaffolding and stamped plate. Given what Leitz had said about the structures being vitreous rather than metallic, the impression had to be reckoned illusory, but it still made the forests and “grasslands” seem radically un-Earthlike. If this world really could be counted as an Earth-clone, Matthew thought, it was a twin whose circumstances and experience had made a vast difference to its natural heritage.

When the low-flying camera eye finally reached the shore of a sea Matthew saw that its surface layer was indeed covered with a richer floating ecosystem than he had ever seen on any of Earth’s waters. The inshore waters were dappled with huge rafts of loosely tangled weed, and the seemingly calm deeper waters were mottled with vast gellike masses. Matthew did not suppose for an instant that they really were amoebas five or fifty miles across, but that was the first impression they made on his mind. He tried to think in terms of leviathan jellyfish, gargantuan slime-molds, oceanic lava lamps or unusually glutinous oil slicks, but it didn’t help. There was nothing in his catalog of Earthly appearances that could give him a better imaginative grip on what he was looking at.

It was difficult to make out much detail from the present height of the viewpoint, but that disadvantage was compensated by the sheer amount of territory that was covered. Matthew was able to see the black canyons splitting the polar ice caps, and the shifting dunes of the silvery deserts. He saw islands rising out of the sea like purple pincushions and he saw mountains rising out of the land like folds in a crumpled duvet.

The mountains had no craters; they did not seem to be the relics of volcanoes. Perhaps, Matthew mused, the continents of the New World had been as richly dotted with extinct and active volcanoes as the continents of Earth a billion years ago, but a billion years was a long time, even in the lifetime of a world. Perhaps, on the other hand, the New World had been just as different then, or even more different. If it qualified as an Earth-clone at all, it was because its atmosphere had much the same precious mix of gases as Earth’s, calculated to sustain a similar carbon-hydrogen-nitrogen biochemistry, not because it was actually Gaea’s twin sister. Perhaps Earth-clonewas entirely the wrong word, applied too hastily and too ambitiously because truer clones had proved so very hard to find—but Matthew reminded himself of what he had told Leitz. He would be better able to make up his mind when he knew all the facts.

The viewpoint became even more intimate, picking out a strange collection of objects that looked like a huge, white diamond solitaire set amid a surrounding encrustation of tinier gems. The whole ensemble was situated on a low-lying island some twenty or twenty-five kilometers from one of the major continental masses.

“Base One,” Leitz told them. “The soil inside the big dome was sterilized to a depth of six meters and reseeded with Earthly life, but there are dozens of experimental plots mixing the produce of the two ecospheres in the satellite domes.”

“Is that where Delgado was killed?” Solari wanted to know.

“Oh, no—he was at Base Three, in the mountains of the broadleaf spur of Continent B.”

“Continent B?” Matthew echoed. “You can’t agree on a name for the world, you’re numbering your bases and you’re calling its continents after letters of the alphabet? No wonder you don’t feel at home here.”

Leitz didn’t react verbally to his use of the word you, but the gaze of his green eyes seemed to withdraw slightly as he retorted: “It’s not the crew’s place to name the world or any of its features, and it’s not the crew’s fault that the colonists are so reluctant.”

But it was the crew who selected and surveyed this world, and decided to call it an Earth-clone, Matthew said to himself. If the colonists have discovered that they’ve bitten off more than they can chew, why shouldn’t they blame the people who woke them up with reckless promises? But why would the crew jump the gun? Why would they decide that the world was ripe for colonization if it wasn’t? He didn’t voice the questions, because maturing suspicions had made him wary and because an appointment had now been set for him to see the captain—the man with all the answers. He would be in a better position to listen and understand when his body had caught up with his brain and he was a little less tired.

“How big is Base Three, compared with Base One?” Solari asked, still clinging to his own tight focus on practical matters.

“Tiny,” Leitz told him. “Only a couple of satellite domes. It wasn’t part of the original plan—Base Two is in the mountain-spine of Continent A, only a few hundred kilometers from Base One, and there was no plan to establish a third base so far away from the first—but when the surveyor’s eyes spotted the ruins the groundlings had to improvise. They’re establishing supply dumps and airstrips in order to create a proper link, but it was very difficult to transport the first party, and we had to top up the personnel with a new drop.”

“Why did it take so long to find the ruins?” Matthew asked.