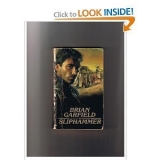

Текст книги "Sliphammer"

Автор книги: Brian Garfield

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

Two

Jeremiah Tree sat his horse on the hillside, crossed one leg over the saddle horn and packed his pipe without hurry, lazy in the heat, a craggy, big man with a weathered, sun-squinted face and leathery little creases crosshatching the brown back of his neck. All around him the desert was in flower-Spanish bayonet, yucca, hummingbird bushes, chollas, staghorns, ironwoods, cat-tlaw, Joshuas, mesquite, paloverde, prickly pe’ar, ocotillo and the little red ones some drunken botanist had labeled with punful helplessness Echinocereus damdifino. Damned if I know, yeah. Didn’t matter if you knew their names anyway. The blossoming beauty of riotous color was a brief annual discovery that always made him feel as if he was going back to some very primitive and basic thing, an innocence and cleanliness long gone.

He put the pipe in a corner of his wide mouth but did not light it. It was too hot to smoke. He sat looking down at the ranch, where the sun seemed to set the corrugated metal shed roofs afire. The hot wind rubbed itself against him with abrasive dryness.

He had been sitting here for an hour, watching the two saddled horses ground-hitched in the ranch yard below. He had a fair idea what the two of them were doing inside, and he didn’t want to interrupt. He chewed on his pipe and waited. Absently, his left hand hooked itself for comfort over the hammer of his hip-holstered six-gun. It was a good fast gun: a fighting man’s gun. Forty-five center fire single action with a 4 %-inch barrel and a front sight that had been filed down low and smooth so it wouldn’t get caught on the holster coming out. It was a sliphammer six-gun: it had no trigger inside the oval guard; the hammer spur had been sawed off, cut down, and rewelded in place halfway down the back of the hammer. The hammer spring had been filed with care. It took a great deal of experience and practice to use a sliphammer gun effectively, but once the technique was learned-scraping the ball of the thumb fast over the lowered hammer spur-a sliphammer shooter could fire three times as fast as a man with a trigger, and far more accurately than an idiot who fanned.

Jeremiah Tree went with the gun: he had a workmanlike look. His face was the color of the worn walnut handle of the gun. His eyes were the color of the metal at the gun’s muzzle where holster friction had worn off the bluing: the silver color of a freshly minted. 45 slug, before corrosion dulled the lead. His skin had the texture of holster leather softened by countless saddle soap-ings. His shirt had been washed too often; the sleeves had shrunk halfway up his forearms. His long-legged stovepipe Levi’s were faded and white-threaded.

His hair was thick and black, curling out under the stained hat, and generally he had the look of an Indian or a half-breed, though he was neither: both parents had been Scotch-Irish. A history of fights was recorded in the myriad ^minor scars and half dozen major ones on his exposed face and hands; victories were implied by the fact that he was neither disfigured nor crippled.

The only clue to his present occupation was the pair of pinholes in the left breast patch pocket of his shirt. He wasn’t wearing a badge today.

Alerted by movement in the porch shadows, he straightened in the saddle and put his boots back into the stirrups. Down there he saw Caroline come out into sight and lift one hand to shade her eyes, looking toward the western horizon. Jeremiah Tree gigged his horse gently downhill.

She hadn’t seen him yet; she was looking the other way. As Tree rode switchbacking down the hillside, he saw Rafe come out of the house ramming his shirt tails into his Levi’s and then sweeping the disheveled hair back out of his eyes. Rafe walked up behind Caroline, reached under her arms and laid both hands on her breasts. The girl tipped her head back against his shoulder.

Tree’s face showed no break in expression. He was thinking of what Caroline’s father had said to him a month ago: I tried to talk her out of it, Sliphammer boy. Honest to God I did. I told her not to marry your brother because he just ain’t tough enough for her. She’ll put spurs to him one time when she ain’t even thanking about it, and she’ll rip him to shreds ‘thout ever knowing how it happened.

He brought his horse around the end of the porch. He heard crickets in the trees down by the spring. A hawk drifted above the house; a dog lay asprawl under the porch, panting in the shade.

Sliphammer Tree said, “Whose dog is that?”

Rafe had taken his hands down off Caroline’s breasts when he’d heard the hoofbeats. Now they were holding hands. Rafe said, “Beats me. Stray, I reckon.”

“Lo the bride and groom,” said Sliphammer with a little smile at Caroline. Husky and blonde, she made him think of haystacks. She had a sturdy, firm body; her breasts seemed so tightly packed and swollen that one good squeeze might bring forth a squirting shower of juices. She had the eyes of an alert doe stepping into a strange clearing.

Caroline said, “Do you like the place?”

Sliphammer had been inspecting the ranch. The buildings were weathered and tumbledown, with the look of abandonment. He said, “It looks lived in-hard to tell by what.”

“Snakes and roaches, mainly,” said Rafe. He was young and very earnest: half amazed by– his own possession of this vibrant, vital girl-wife he had, he had turned eager and flushed, and impatient with ambition. It troubled Tree but he had said nothing in the past week; once they had got married it had seemed too late for avuncular advice. The kid would have to make his own mistakes.

Rafe seemed irritable just now: his brown eyes flashed erratically. He was chunky and broad through chest and shoulder; in a few more years when he filled out completely he would be a powerful man. His jaw was wide and blunt. He had Sliphammer’s long bladed nose and the shape of his cheekbones and eyes was the same, but his bone structure was heavier, less graceful, and his coloring was lighter. They had shared the same father but different mothers: the frontier was hard on women.

Rafe said, “Damn it, do you like the place?”

“Looks like you’ve already got your minds set on it. Do you need my approval?”

Rafe’s chest swelled but Caroline cut him off: she said, “We think we can make a good place out of it, Jerr.”

She was the only one who’d ever called him that. He’d been called Jeremiah, Jerry, Jeremy, and Sliphammer. The West didn’t seem satisfied with a man until it had surrounded him with descriptive nicknames. Caroline’s father called her the Milkmaid, and truly she looked like one. Rafe was known as Wrangler Tree because his specialty was horses.

The house creaked, settling. Rafe said in a pushy, defiant voice, “Make a goddamn good horse ranch out of this outfit. Take a little cash and a lot of sweat but we’ll do it proud.”

In spite of himself Sliphammer said, “You’ll do as you see fit, I reckon, but maybe it’s a little early to chance it on your own. First of all you haven’t got the money to buy the place, and if you do it on borrowed cash all it’ll take will be one bad season to wipe you out. A man ought to have a nest egg before he goes into business on his own.”

“We’ll take the chance.”

“That’s what the last fellow thought who owned this place. Why do you think it’s up for sheriff’s auction?”

“Because the last fellow didn’t know how to run a ranch, which is not my weakness,” Rafe snapped. “For a man who’s worked for wages all his life you’re mighty free with your advice, Jeremy. I’m a married man and Caroline deserves a whole lot better than a thirty-a-month wrangler. You work your whole life for dirt wages and end up with nothing to show for it and when you die your friends got to take up a collection to bury you. That ain’t for Caroline and me.”

Caroline pushed her lower lip forward to blow hair off her forehead. Sliphammer said to her, “You agree with that?”

“If I didn’t I wouldn’t be here.”

“Hell,” said Rafe, “I got to admit it was Caroline’s idea in the first place.”

I should have known, Sliphammer thought. What he said was, “With a little luck I guess you might make it.” There was no point in arguing with them.

“Bet your ass we’ll make it,” said Rafe. Caroline blushed, and Sliphammer found that faintly surprising.

Rafe lifted his arm and pointed. “Somebody coming.”

Sliphammer turned to follow his gaze. He had to tip his head to get the sun out of his eyes. A rider was coming down the blossoming slope, neither hurrying nor wasting time. Rafe said, “Looks like your boss.”

It was in fact the sheriff, Bob Paul. He had a pinched, exasperated look on his heavy-jowled face. Paul had spent his whole life in the saddle but he still managed to look like a sack of potatoes on horseback. He was a rounded man, rounded everywhere: his thighs looked soft, his shoulders were matronly, his darkly beard-slurred face was puffy. He was a solemn, slow-moving man, a good sheriff, an acceptable boss, a casual friend.

Paul’s greeting was dour. “The one day in the year I really need you, you’re galivant-ing way the hell out here. Don’t you thank I’ve got better thangs to do than chase all over Pima County thew this heat? H’are you, Wrangler? Missus Caroline?”

Paul touched his hat. Sliphammer was smiling, not rising to the bait; he said mildly, “Even us slaves get a day off now and then.”

Paul removed his hat and wiped his face in the crook of his sleeve. “My frin, I’m jis gonna have to hang a bell on you.”

“I repeat,” Sliphammer said good-humoredly, “it’s my day off. You want to talk to me today, pay me an extra two dollars.”

“Ain’t nothing like a loyal deputy,” Paul complained with a great show of indignation. “And as for these kin of yours, you ever notice how these young folks lose all their manners? Ain’t nobody invited me to step down and take a little drank.”

Rafe said, “You’re welcome to light down. There’s nothing to drink here until somebody deans out the well. Or you can go down to the spring.”

Paul climbed down with a fat man’s sigh. “Get that well fixed soon as somebody buys the place at auction next month. You still in the market?”

“Bet your ass.”

“Likely you’ll have to scramble some, then. Get yoseff plenty of money. Fellow from Prescott’s gonna brang me a bid of three thousand dollars, I hear.”

Rafe’s face fell. Caroline said, “Three thousand?”

“That’s what I heard,” said Paul, and turned toward Sliphammer. “Rat now you and me got binness.”

“It’s still my day off.”

“Neither one of us gonna get no more days off for a while, Jeremy. We got ourselves a little chore up to Colorado.”

“Colorado?”

Paul nodded. He tramped over to the shady corner of the house and sat down on the sagging edge of the porch, his face pearled with sweat. “Come acrosst here and set down.”

Sliphammer went over and sat by him. Rafe and Caroline hovered, listening, and Paul made no effort to chase them off. He said, “Superior Court put out a fugitive bench warrant for the Stillwell murder last nat.”

“On the Earp crowd?”

“Just so. Wyatt Earp made a mistake pointing his fanger at Frank Stillwell-Stillwell had a lot of frinds and one or two of them got the Governor’s ear. Got a lot of Texas cowmen in Arizona that never did like the Earp gang, just lookin’ for an excuse like this. Now, Stillwell got killed in this jurisdiction, and that makes it our job to brang the Earps back from Colorado.”

Paul looked up at him. His fat face seemed boyish and sorrowful. “It sets up like this, Jeremy. The gang busted up after Stillwell got killed. Texas Jack and a couple others got lynched to death over to New Mexico, which leaves three Earp brothers and Doc Holliday. Now, Virgil went on back to Ohio with Morgan’s body. Ain’t nobody interested in crucifying Virgil-he’s crippled up anyway, everybody knows he couldn’t of shot anybody. But I got these warrants for Doc Holliday and Wyatt and Warren Earp. They all up in Colorado-Holliday’s bucking faro in Denver and the other two, they over to Gunnison on the southwest slope of the Rockies. Up to you and me to serve the warrants, boy.”

When Sliphammer didn’t speak, Paul glanced at him again and said morosely, “I can’t go both places at once, Jeremy.”

“So I’m elected to arrest Doc Holliday?”

“No. The Denver police will do that.”

“Then-”

“Aeah. I got to be the one to go to Denver, you see-I got to get the Governor of Colorado to sign the extradition papers before we can arrest anybody. You got to be the one goes to Gunnison, Jeremy.”

Wyatt Earp. Tree studied the toes of his sunwhacked boots and wondered how much registered on his face. It was unthinkable-like trying to arrest Robin Hood or Ulysses or Buffalo Bill.

Sheriff Paul’s voice droned on: “You ain’t to arrest them, not at first anyhow. While I’m dickering with the Governor I want you in Gunnison where you can keep your eye on Wyatt and his brother. Soon as I get the papers signed in Denver, I’ll send you a telegraph ware, you get the sheriff down there to hep you. I don’t know how many deputies he’s got but I reckon you’ll get plenty of hep. All you got to worry about is branging them back here and making damn sure they don’t bust loose.”

“Uh-hunh,” Sliphammer said absently.

Half the porch length away, Rafe was unable to contain himself: he blurted, “Sheriff, you think Wyatt Earp’ll take kindly to the idea of being brought back to Arizona to get hung?”

The sheriff gave him a long, slow look. “Why, no, son, I don’t thank he’ll take kandly to it at all.”

Caroline said, “You can’t mean this.”

Paul shook his head mutely and got to his feet with a grunt.

Sliphammer said, “I don’t take kindly to it either.”

“Scared, boy?”

“Maybe.”

“I ain’t worried about you.”

Sliphammer said, “That’s a comfort.”

“You ain’t a frind of Wyatt’s, are you?”

“I’ve never laid eyes on him.”

“Then that’s dll rat,” said Paul. “Listen here-he uses a privy the same way you do.”

“Yeah.”

Paul nodded sagely, and walked toward his horse. Sliphammer kept his seat, and the sheriff looked back at him inquiringly.

“Jeremy, I sure hope you ain’t thanking of refusing to do this little chore.”

“Maybe I am.”

“No. Long as you work for me, Deputy, you take awders from me. I can’t have a deputy that only works when he feels lak it.”

Caroline said, in awe, “But you’re talking about Wyatt Earp!”

“I thought I was,” Paul agreed. “Now look here, Jeremy, it’s too hot to stand here arguing for ahrs and ahrs. How about you get yoseff acrosst that horse? We got some traveling to do.”

Rafe was still on the porch with Caroline. He was frowning at Sliphammer, who got slowly to his feet. Rafe swung toward the sheriff and said abruptly, “They posted any reward on Wyatt Earp, Sheriff?”

“I regret to say they have.”

“How much?”

“It ain’t my doing. Cochise County put twenty-five hundred dollars on Wyatt Earp and fifteen hundred each on. Warren Earp and Doc Holliday. I reckon they’ll throw in Wyatt’s wife for nothing.”

“Then a man could get four thousand dollars for bringing Wyatt and Warren back.”

The sheriff shook his head. “Rafe, your brother’s a peace officer. He ain’t entitled to collect no bounties.”

“But a private citizen can,” Rafe said. “And I’m a private citizen. Woop!”

Sliphammer wheeled toward him. He spoke flatly: “No.”

“No what?”

“Don’t even daydream like that, Rafe.”

“Caroline and me need the money. I’m coming with you.”

“The hell you are,” Sliphammer said. “In the first place you’re no match for the Earps. In the second place it wouldn’t be right to take blood money for a man like Wyatt Earp. And in the third place you haven’t got the money to pay the train fare to Colorado in the first place.”

Rafe took one step forward. “We’re brothers, Jeremy. You owe me.”

“We’re half brothers,” Jeremiah Tree growled. “And I don’t owe you anything you don’t earn, Rafe.”

Caroline said, in a voice with a low husky quality to it, “You’re so damned honest, Jerr. Why do you have to be so damned honest?”

Rafe said petulantly, “It ain’t fair!”

Sliphammer looked at him. He said, “Fair, my ass.” He turned and walked to his horse.

Rafe made both hands into fists and got up on his toes as if he were about to fall forward. The sheriff said to him, “Gentle down, Wrangler. You got no binness in this kind of thang. You two just go on being Mister-missus Tree and raise a pack of churiren and wrangle horses. It took your brother here fifteen years of professional Indian fighting to learn how to use a gun and even-he knows enough to be scared of Wyatt Earp.” Paul turned, gathering the reins, and heaved himself into the saddle with considerable ungainly effort.

When Sliphammer stepped into his saddle, Caroline said to him, “Jerr, you be careful, hear?”

He gave her a long look, as if to pin her image in his memory; he waved at the two of them on the porch and swung his horse in alongside the sheriff’s. They rode out of the yard together. Behind them Rafe and Caroline stood and watched, arms about each other’s waists. Sliphammer looked back until the corner of the sagging house cut them off from sight. As he turned forward he saw himself, his shadow on horseback, riding along by.

The flayed landscape stretched away west across the great baking pan of the desert. On the far horizon he could see scattered clouds. He could smell a change in weather coming.

Sheriff Paul’s voice startled him: “I don’t want you going into this thang all hetup. If you really don’t want the job you better quit now. I’ll get somebody else.”

“Who’re you going to get to pin on a deputy doodad when they could do the same thing without it and collect four thousand dollars’ reward?”

“Don’t fret yoseff none. Plenty of fools in the same barrel you come from.” Paul grinned at him. He had a lot of gold teeth.

“I guess I’ll keep the joh.”

Paul said, “I thought you would. I mean, if you quit, what you gonna do then? Go back to Indian fighting? The Indian wars are all over. What choice you got? Naw, you’ll do it. I never doubted you would.”

There followed Paul’s short grunt. Sliphammer was thinking, a bit sourly, that it had always been his one incurable weakness-the infantile faith with which he always refused to fold a pair of jacks in the face of a big raise. The fact was, he wanted to meet Wyatt Earp.

Three

The train brought him up a green valley at dawn, with the sky brightening cobalt and full daylight just cresting the westward peaks, dazzling the snow caps. Up ahead, green meadows ran up curving slopes into forests of aspen and pine. Here and there on the mountains he saw the thick columns of mill and smelter smoke.

The train threaded a field of brown-eyed yellow daisy buds and made a long, easy bend. Past the high, narrow locomotive he saw signs of civilization by the tracks: a dairy farm, a few houses, a deep-rutted ore wagon road, wooden mailboxes at graveled intersections. The train curled past a brewery and a small paint factory and a cement mill covered with gray powder. Sidings of polished rails began to proliferate beside the main line. Through the trees ahead he could make out the packed buildings of end-of-track Gunnison town. The bank of the river pushed close against the railroad yards; the train sighed and clanked and eased into the station gingerly.

Gunnison was a new town: two years ago it hadn’t been here at all. Trees grew thick everywhere there wasn’t a building because there hadn’t been time to clear land that wasn’t needed for immediate use. A few trees even grew in the streets.

Sliphammer Tree jumped down before the train had come to its full stop; he walked across the depot platform with a carpetbag in his right hand and a sheepskin-lined mackinaw under his arm. The sun’s rim sat on top of a mountain saddle. His lank, tall, striding body threw a long, skinny shadow.

He went around to the front loading deck, built as high off the ground as a freight wagon’s tailboard. Four steps, cut into the platform, let him down onto the street. He looked both ways before he went on.

The town was crowded together by trees and by the knees and elbows of mountains. It seemed without regular pattern; the center of activity seemed to be a few blocks north of him, signified by a cluster of two-story buildings with pitched roofs. He went that way. Sidewalks appeared, guarded by glassed-in gaslights on posts. He passed stores, an opera house, saloons, the Globe Theater, even a bookshop. Obviously the city fathers had foreverness in mind. The buildings were sturdy, some of them enormous, with the shambling, graceless opulence of Victorian splendor. The only giveaway that most of them had been thrown up hurriedly was that they were built of green lumber, already starting to warp and yaw.

It was cool; a few pedestrians were abroad; a water wagon trundled along, spraying the street to keep the dust down. Here and there shopkeepers were opening their establishments. Smoke came from a Chinese cafe’s kitchen and hunger drove him that way.

Procrastinating, he sat by the front window at a table hardly big enough for a plate and two elbows, wondering what Wyatt Earp was like. Steak, eggs, and coffee came; he knocked the flies off and began to eat. It was fresh-killed beef, not aged, and he had to work his teeth on it; the coffee was the chuckwagon variety-“If you put a horseshoe in it and the horseshoe sinks, it ain’t strong enough.” He paid for the two-dollar breakfast and wondered how long he would be able to survive these boom-town prices; gathered up his carpetbag and coat, and went out. The streets were busier than they had been. He threaded his way across the street through a traffic of ore wagons and buckboards and solitary horsemen, into the narrow lobby of a small hotel; awakened a drowsing night clerk and signed “Jeremiah R. Tree” in his crabbed hand; and found his way back to a first-floor room with a six-foot ceiling that made him stoop. The room was hardly big enough to accommodate the iron-frame, straw-tick bed and the commode. He filled the pitcher at the hallway pump,” washed in the commode basin, left his carpetbag and coat in the room, and locked the door when he left. Three paces down the hall his boot scuffed a hard object in the accumulated dust of the floor and he stooped to pick it up-a tenpenny nail. After a moment’s speculation he returned to the door of his room and wedged the nail between door and jamb, at a distance below the top that matched the length of his forearm from fingertip to bent elbow. If anyone opened the door, the nail would fall out, and even if the intruder noticed it and tried to replace it, he would not’ know exactly where it had been.

It was habit, he thought; not that he owned anything worth stealing. But he didn’t want to be caught by surprise by someone waiting inside the room.

By the time he reached the street the traffic was intense. Dairy and egg wagons crowded past huge ore rigs and ten-team freight outfits with riding mule skinners who whooped and cursed. Standing above the dust and din, he put the pipe in his mouth and struck a match to it, and squinted along the street, wondering which one of the buildings housed Wy att Earp and company.

A block away, on the same side of the street, two men stood outside a doorway. They were looking at him. He stared back. One of the men pointed at Tree, spoke to his companion, received the man’s nod, and went away. The man who remained was tall, lean, and white-haired. He lifted a long arm and beckoned.

Tree looked behind him, but there was no one else the man could have been signaling. With one eyebrow cocked, he left the hotel porch and walked upstreet toward the white-haired man, who waited without a smile, stirring slightly so that he came into the bladed edge of the sun falling past the corner of the building. A badge on his shirt picked up the light and lanced it into Tree’s eyes.

Tree was still half a dozen paces away when the white-haired man spoke; the voice was deep and curiously well modulated: “I’ve got a pot of fresh coffee inside if you’d care to join me.”

Without waiting an answer, the white-haired man turned inside. It was, Tree saw now, the sheriff’s office; a little shingle sign above the door said GUNNISON COUNTY SHERIFF: O. J. McKESSON.

When Tree went inside, the white-haired man was standing by a black iron stove whose chimney pipe staggered back to the ceiling corner in a series of steplike elbows. It made the room look more like a foundry boiler room than an office. A corridor of jail cells lay past an open door at the back of the room. There was a rolltop pigeon-hole desk against one wall, flap open and cluttered; there was the obligatory locked rack of guns; and there were three chairs and a spittoon. Otherwise the room was bare, uncluttered, and scrupulously clean, reflecting the careful dress and manicured appearance of the white-haired man himself. It didn’t remind Tree of Sheriff Paul’s office in Tucson, where every day for the past year and a half Tree had had to pick a path through an incredible litter.

Tree absorbed it all in the time it took his alert eyes to sweep the room once. When he let the screen door slam behind him on its spring, the white-haired man was holding up a coffee pot andpouring into two tin cups both of which were hooked to one finger. The coffee steamed as it flowed out of the pot.

The white-haired man put the pot on the stove, set one cup on a corner of the rolltop and gestured toward it. “Help yourself. You’re Tree?”

“Yes.”

“I’m McKesson.” The white-haired man offered his hand. The fingers were long and brown; his handshake was hard and brief. Up close, the elegance of his face was marred by the rough pitting of an old skin disease.

“Have a seat-let’s talk.” McKesson sat down, blew across his coffee, and watched Tree from under thick, white brows. He was obviously aware of the impressive effect of his suntanned face against the bright white thick hair. Every body movement was made with self-conscious poise. He had hawked, predatory features, fingers like the claws of a bird of prey, gleaming violet eyes that missed nothing.

Tree said, “You know who I am, then you know why I’m here.”

“I had a wire from Sheriff Paul.” McKesson had large white teeth; they formed an accidental smile when his lips peeled back from the too-hot coffee. He lowered the cup and licked his lips and said conversationally, “Personally, I’d advise you to forget it, young fellow.”

“Forget what?”

“Wyatt Earp. He’ll destroy you-he’ll swat you like a fly, if you get in his way.” Absently, he made a face at the coffee and put the cup down to’ cool. He leaned back, crossing his legs and hooking one arm over the back of the chair, and in a sleepy way he added, “You’ll never get him out of this town if he doesn’t want to go.”

“Funny way for you to talk,” said Tree.

“Why? Because I wear a badge and you and I are supposed to be on the same side?”

“You might say that.”

“I might, but I won’t. You see, I’m an elected official with a duty to the constituency that voted me into office.”

“What’s that got to do with Earp? He didn’t vote for you.”

“His friends did,” McKesson murmured, smiling a little. He was being deliberately mysterious and it irritated Tree.

Tree said, “All right, since you want me to ask. What friends?”

It made McKesson laugh. “Very good. I’m glad to see you’re not the usual kind of bumbling half-assed farmer they use for deputy sheriffs down in Arizona.”

“Spare me the kind words, Sheriff. Get to the point, if you’ve got one.”

One bushy white eyebrow went up, a warning sort of expression that might have been accompanied by tongue-clucking. “Easy, young fellow,” McKesson said. “You haven’t got so many friends in his bailiwick that you can afford to alienate me.”

“I didn’t know we were friends.”

“I’m doing my best to be friendly,” McKesson answered. “I’m trying to give you some advice that may save your skin. What could be friendlier than that?”

“You said something about Wyatt Earp’s friends.”

“Friends,” the sheriff echoed. “Everybody’s somebody’s friend.” His hard smile did not give him the disarming appearance it was evidently intended to provide.

Patiently, Tree reached for the coffee and tasted it. It was a far cry better than the Chinese cafe’s.

McKesson said, “You’ll have to forgive me. I like to act as if I’m absentminded and vague-as if I’m not aware of events. It’s often an effective pose-it puts people off their guard, which makes it easier to get around them and cut them off. I should warn you I’m an overeducated old fart but I’m not as slow as I appear.”

“I’ll bear it in mind.”

“You do that. Now, about Earp and his friends. You arrive here one bright sunny morning all by yourself, evidently expecting to be able to do single-handed what a small army couldn’t do. In the interests of keeping the peace, which is what I’m hired to do, I feel it’s incumbent on me to alert you to the realities of the situation you’re in. You’ve been posted up here to keep surveillance on the Earps until you get word from Denver that Governor Pitkin’s signed the extradition papers. At that point you’re supposed to arrest Wyatt and Warren Earp and take them back to Arizona in custody. Is that right?”

“Sure.”

“Do you think you can do that? If you do, you’re a fool. How do you expect to pull it off?” McKesson looked as if he were genuinely curious.

Tree gave him a long scrutiny, trying to see past the mask of wordy pomposity. Clearly McKesson was, as he said he was, a lot faster than he appeared: if he wasn’t, he wouldn’t have this job. A mining boom camp was no place for an addle-headed old law man.

Tree decided it might be profitable to play McKesson’s own game. And so he said, “Let’s put it this way. If I don’t have a plan, I’d be stupid to admit I was that much of a fool. And if I do have one, I’d be stupid to tell you what it is.” And he smiled.

The white eyebrow went up again. “Smart,” McKesson commented. “Smarter than I took you for-and coming from me that’s both a compliment and a confession. I rarely fail to size a man up correctly at first crack. You took me by surprise twice. Either I’m slipping or you’re a damned clever young man.”