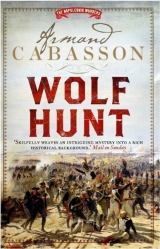

Текст книги "Wolf Hunt"

Автор книги: Armand Cabasson

Жанры:

Исторические детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

No one was paying any attention to this regular customer. Beethoven did not have to place an order; since he was a habitue, the waiter knew to bring him coffee and cream. Saber was visibly excited.

‘Have you never heard his Third Symphony? It’s fantastic. He dedicated it to Napoleon!’

At these words, Luise stifled a laugh but said no more. She wore the joyous impatient expression of someone who knew what little catastrophe was about to take place and was keen not to ruin it. Saber would not stop talking about the maestro’s melodies. For his part, Margont, who was incapable of reading a score, understood little of what was going on. Saber had chosen to quench his absolute thirst with the great wins and the disasters of military life, but it seemed his thirst also extended to music. Without wars, would he start to churn out musical scores? Saber grew breathless.

‘It’s the fifth time I’ve seen him. He always just slips in.’

‘Have you spoken to him?’

Saber groaned. ‘No ...’

Margont had seen his friend’s bravery at first hand on the battlefield and here was Saber speechless in front of a man he admired. ‘Herr Beethoven, I am Lieutenant Irenee Saber. Allow me to say that I find your work absolutely sublime.’

Beethoven did not react. He drank his coffee, still wrapped up in his thoughts. His face and his gestures betrayed tension. His dreams were filled with rage.

‘Herr Beethoven?’

A customer came to Saber’s aid.

‘He’s almost deaf,’ he said in hesitant French, covering his ears with his hands to make himself clear.

‘How can a musician be deaf?’

‘Why not? He could hear before/

‘Yet he’s still composing ...’

‘He hears in his head.’

The Austrian tapped his temple as he said that. He burst into the raucous laughter of a pipe-smoker.

‘No one takes him seriously,’ he added.

‘Don’t say that. He’s a genius, you ... hypocrite!’ retorted Saber vehemently.

The customer beat a retreat, glass in hand, disappearing into the crowd. Saber smiled again and leant towards Beethoven’s ear, raising his voice.

‘Herr Beethoven? I’m Lieutenant Saber. I wanted to tell you—’

The maestro swung round suddenly to face him. His face was covered in scars, the result of smallpox, and his glasses magnified his eyes.

‘Don’t talk to me! Damn you French!’

His cheeks had become purple, emphasising the whiteness of his voluminous, old-fashioned cravat.

‘What’s become of your revolution? You launch your wonderful republican ideas on the world and then you found an empire! Napoleon has betrayed us all!’

‘I want to talk to you about your music ...’

‘Let go!’

But Saber had not touched him. Beethoven hurried to the door, knocking into customers.

The owner leant over his counter to shout: ‘Herr Beethoven! You haven’t paid! It’s not free here for musicians and poets.’

‘I’ll pay for him,’ declared Saber, throwing a handful of kreutzers at the owner.

Disconcerted, he rejoined his friends. When she did not like someone, Luise could be scathing. She looked at him contemptuously.

‘If I may correct you, Beethoven did not dedicate his Third Symphony to Napoleon, but to the revolutionary, Bonaparte. At the time he used to harangue the nobles in the public gardens to tell them that all men are equal, that monarchy was a thing of the past ... As Beethoven is an extraordinarily touchy man, persuaded that all the world is out to get him, he’s always involved in confrontations. He fell dramatically from favour when your Bonaparte became Emperor. He destroyed the title page of his Third Symphony, which is now called the Heroic Symphony, and it is dedicated to one of his patrons, the Prince Lobkowitz. Oh, yes, it’s such a shame that Beethoven ruined your sugary war game.’

CHAPTER 16

IT was hard to persuade Relmyer to come to Schonbrunn. The Hofburg Palace was the official home of the Court, but it was decaying and rather impractical because of its dispersed buildings. Emperor Francis I preferred the Chateau de Schonbrunn. So did Napoleon, and he had installed his headquarters there. To show the Viennese that the little setback at Essling had in no way dented his determination, he regularly reviewed his troops at Schonbrunn, that symbol of Austrian power. Today, as frequently happened, an assorted crowd of people hurried into the gardens to watch the spectacle.

An immense park had been decked out in the French style with flowerbeds, shaped hedges, lines of trees ... Symmetry was the golden rule. A fountain of Neptune, statues and fake Roman ruins paid homage to the fashion for antiquities. Right at the end, on a little hill, a pavilion with columns presided in splendour, an invitation to gaze at the view. This park was not of its time.

Schonbrunn was like a little version of Versailles. The ochre facade suggested appeasement. It was governed by subtle mathematical and architectural rules. The result, harmonious, elegant and aesthetic, was a pleasure to behold. In front of the chateau, several regiments waited. Their white gaiters, breeches and tunics shone in the sun, contrasting with the dark blue of their coats. As the Emperor was not yet there, there was complete stillness.

Lefine was overcome with a fit of the giggles.

‘You would think that time had stopped down there.'

The crowd pressed against the sentries charged with keeping it at a distance. Soldiers mingled with the Austrians, some curious and some sympathetic to the republican or imperial cause. Several women had secured places at the front to charm Napoleon. Were they being seductive? Defiant? Greedy? Did they harbour ambitions? Was it love or fascination? Some were so exquisitely beautiful that the Emperor could not fail to notice them if he were to pass close by.

Margont noticed that Relmyer had a sort of tick. His eyes were moving all the time. They ricocheted from face to face, rarely lingering, never finding repose. He had acted the same way in the streets, but here the mass of people accentuated his behaviour, making it more obvious. He’s looking for him, thought Margont. If Relmyer suddenly saw him here – or thought he saw him, because his memory of his gaoler had altered over the years – how would he react?

A clamour arose. There were shouts, and cries of ‘Long live the Emperor!’ A black berlin arrived, escorted by the chasseurs of the Imperial Guard in their green uniforms, their red pelisses thrown over their shoulders, their sabres unsheathed. There followed an interminable, sumptuous procession of officers of the general staff, the gold embroidery on their blue coats sparkling. The cavalry were distinguished by the originality of their uniform. One of them, a dragoon, wore a dark blue coat and a crested copper helmet in the style of Minerva, decorated with a black plume and banded with sealskin; another, the Mameluke Roustan, wore babouches, red baggy trousers, a short blue jacket and a white turban (his ostentatious presence was a reminder that Napoleon, when he was still Bonaparte, had conquered Egypt, albeit briefly). This river of prancing colour and the frenetic excitement of the public contrasted with the immobile, impassive infantry of the line. The crowd tried to draw nearer, but could not get past the sentries barring its way.

Lefine sounded a sour note: ‘That’s right, long live the Emperor! We won’t be saying that when we receive our pay late.’

Napoleon stepped out of the berlin. Emaciated at the time of the Consulate, he had now become stout. His neck was so short that his round head seemed to perch directly on his torso. In spite of the heat he wore a long grey greatcoat and his black bicorn. He was strikingly short, but radiated energy and an intimidating authority. This contradiction was unsettling. Many Viennese hated him. They had come to gaze at ‘the monster’. Many times they had imagined how they would sneer at the Emperor, taunting him as a dwarf, a bloody tyrant, a jumped-up nobody, an ogre ... but now they were struck dumb. They had counted on seeing ‘the vanquished man of Essling’ and instead they were faced with a leader bubbling over with self-assurance. It had been said that during the battle everything had gone wrong for him. Yet the Emperor smiled, joking with an aide-de-camp. He was behaving like ... like a conqueror! In reality Napoleon was projecting an image and he imbued it with astonishing realism.

A general shouted an order and the soldiers briskly presented arms. Moving stiffly, Napoleon began to walk along the line, his hands behind his back, accompanied by two officers of his general staff and two colonels. Sometimes he would pause in front of an infantryman long enough to pose a question, or to repeat one of his sayings, which the army took up in an endless echo: ‘Soldiers,

I am pleased with you’ (the evening after Austerlitz), ‘War between Europeans is civil war’, ‘Action and speed!’, ‘That can’t be allowed: that’s not French!’ ... Margont could not understand how Napoleon could appear so serene while his world was at risk of collapsing any day now. Such self-control inspired confidence.

Now I’m falling under his spell, he reproached himself.

Napoleon speeded up, hurrying, hurrying. The crowd groaned, put out. Was he leaving? So soon? Was he not going to approach before he left? The Emperor questioned two other colonels, turned about and hurried off towards his escort. Some soldiers shouted again, ‘Long live the Emperor,’ while the beautiful girls made eyes at the sentries to try to get them to bow. An imperceptible eddy ran through the crowd in response to Napoleon’s slightest gesture. Margont watched the little grey figure go back up the white and blue line of soldiers.

Suddenly two boys escaped from the throng, pursued by a corporal. Other sentries came from behind to bar their route. The two young men had underestimated the speed of reaction of the infantrymen and were taken unawares. They took stones from their pockets and hurled them in the Emperor’s direction, yelling, ‘Long live Austria!’ Their stones landed in the flowerbeds as Napoleon, who had noticed the incident, disappeared into his berlin. A grenadier grabbed the outstretched arm of one of the boys and yanked it upwards, forcing the boy to let his missile go, like a giant disarming a midget.

‘Little beasts! I’ll tan your hide!’

There were protests from the public. How old were these two daring lads? Fourteen? The commander in charge of the cordon let them go, saying, ‘We only hunt the big game.’

‘We’ll get them when they’re big then,’ retorted the grenadier bitterly. ‘And then it won’t be the belt, it’ll be the firing squad.’ Margont caught Relmyer by the arm. He was unaware that he was pinching him.

‘That’s how our man operates! That’s how he was able to drag Wilhelm with him. Wilhelm wanted to join the Austrian army and his murderer led him to believe that he was going to help him cross the border and then to enlist.’

The crowd broke up around them but Margont was not paying attention to that.

‘It’s impossible to cross a river while threatening someone with a pistol. And you can’t pass through enemy lines with someone who wants to be noticed and is trying to escape from you. That doesn’t

make sense. If the murderer had regularly run risks like that he would have been caught long ago. He must have discovered that Wilhelm was hostile to the French.’

‘But how?’ Relmyer immediately asked.

‘He must sometimes go to the area around Vienna. He has already done that at least once, when he was taken by surprise with Wilhelm on the road back.’

These words reinforced Relmyer’s feeling of an invisible threat that he had had now for so many years. A latent, formless, malleable danger, a sort of thickness in the air, which was both variable and oppressive.

‘He looks for boys who are critical of the French,’ went on Mar-gont. ‘He could very well be here now, in the crowd, and have noticed the demonstration made by those two young boys. See how easy it would be. And it would be easy for him to elicit confidences, since he is Austrian. He’s worked on his technique. Now instead of forcing, he convinces. He doesn’t threaten any more, he seduces. That way he can easily lead his victim where he wants him; the victim willingly co-operates. He has adapted to circumstances and uses them to his own advantage. He chooses someone in French territory and takes them over to the Austrian side before taking advantage of them. He does admittedly run risks crossing lines, but with his exceptional knowledge of the woods and marshes of the area, the risks are limited. Moreover, riding between the two zones confuses things and helps him cover his tracks. Anyone who disappears in the French zone will only be looked for in that zone. Our man therefore puts his victims out of reach of anyone who might help them.’

Spelling out his deductions, Margont was cocooned in a universe of concepts, theories and speculation, spun out of ideas. This protected him, keeping at bay emotions, which Relmyer, on the other hand, felt the full brunt of. Wild-eyed and sweating, he appeared ready to succumb to rage, or exhaustion, or perhaps illness ... ‘Wherever he goes,’ he said, ‘he will never be out of my reach.’

‘Now he’s choosing people whose name their nearest and dearest would not be surprised to find on a list of men killed in action.

He’s covering his tracks even better than previously.’

Margont looked again at the long line of regiments a general was addressing. The scene was exactly the same as earlier but, to him, it now meant something different. Now it seemed menacing. It was no longer reassuring; on the contrary, it had become the involuntary ally of peril. The soldiers broke rank, as the grains of a wall of sand rapidly disperse.

The more troops arrive, the closer we are to the moment of battle. We can almost say with certainty that the man we’re seeking will try to get hold of another boy before the next confrontation. Whatever the outcome, the war will move on far from here, either following the retreating army, or it will be suspended. So the murderer has an incentive to act quickly.’

Relmyer’s torment was without end. ‘Perhaps it’s already too late.’

‘I don’t think so. It would be very risky to kidnap another young man from Lesdorf. Two disappearances so close together would attract attention.’

‘Several of my hussars are keeping a watch on the orphanages in the area and will spot him if he approaches.’

‘No, he’ll go looking elsewhere. But he will still need several days to pick out a potential victim and to gain his confidence. However, time is against us.’

CHAPTER 17

THE days passed; military routine was established. It was almost possible to forget that shortly people would die in their thousands ... Lefine was leaning against a chestnut tree, contemplating the branch of the Danube that separated the Isle of Lobau from the Austrians. He liked having a few moments to himself in a calm spot, far from Margont, whose constant activity tended to wear his friends out. Sure enough, here he was on his way over. Lefine cursed himself for not having taken himself further away from the regiment. He could tell what Margont was about to say.

‘Let me guess: your investigation is not progressing any more; you’re going round in circles. The Emperor is everywhere at once, the army is struggling to accomplish a thousand tasks, the Austrians are entrenched beyond Aspern and Essling ... Why are we bothering? Look on the other side of the Danube: it’s exactly the same over there. Why don’t we just stop now; there would be half the world for Napoleon and the other half for the Austrians? We would leave them Russia, India, China, Japan and all that they can find beyond, if there is anything beyond.' Lefine spread his arms wide to illustrate the proof of his idea. 'The world is a big pear: well halve it equally.’

‘Instead of talking nonsense, you could think about our investigation. You’re the one who always has ideas ...’

‘Oh, I have thought about it, would you believe! I’ve even thought of a suspect.’

‘You have? Who would that be?’

‘Relmyer. If he’s the murderer, it explains everything. It would have been easy for him to lead Franz to that old deserted farm because they were friends. There he killed Franz for some reason or other: vengeance, jealousy, unnatural desire, or bloodlust. Then he invented the story of the “evil stranger” to cover his tracks. That’s why the man we’re hunting leaves as few traces as a ghost – because he is in fact a ghost who exists only in your head.’

Margont realised that Lefine did not really believe any of that. Nevertheless the latter expounded the theory as if he did believe it because he knew that it vexed his friend. Subjected to Margont’s authority, from time to time he enjoyed reversing the roles.

As Margont turned pale, Lefine went on with increased assurance, ‘No sooner does Relmyer return than a new crime is committed. That’s no coincidence. Relmyer wanted to do to Wilhelm – whom he knew! – what he had done to Franz. But he was surprised by a patrol he managed to escape from because he had lived in the region. As for those orphans killed at Austerlitz, they were actually killed at Austerlitz. We both fought in that battle, didn’t we? Have you forgotten all those dead and wounded littering the ground? You’re in love with Luise and you’re confusing your childhood story with hers and Relmyer’s. So Relmyer is able to manipulate you. You’re looking everywhere for a murderer who's right under your nose and who must be laughing up his sleeve. Sometimes he who shouts loudest has the most to hide.’

Margont was so shaken he had to lean against a tree.

‘How you can imagine something so horrifying?’

‘I’m not imagining anything. I’m opening my eyes and observing humanity. Whilst you’re torturing yourself with your hypotheses, I have done my researches to try to verify mine. Relmyer did not murder Wilhelm: he was with his hussars when the sentries spotted the two figures on the little island. Besides, if Relmyer had killed Franz he wouldn’t have taken us to see the farmhouse – he would have kept us well away.’

Margont looked taken aback. ‘You really believed that Relmyer could have ...’

‘Of course.’

Lefine was capable of evoking the worst abominations with fatalistic resignation while Margont persisted in ignoring that facet of the world.

‘Why didn’t you mention it?’

‘Because you wouldn’t have listened to me. So I had nothing to suggest. But I did eliminate a potential suspect.’

Although he did not agree with Lefine, Margont recognised that he was right about one thing: Margont did identify with Luise and Relmyer’s personal histories. The memory of his years shut up in

the Abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Desert was still vividly painful. He had suffered not just from the loss of liberty but also from the pressure to become a monk, that is to say, to become someone he was not. At the time, his family had thought that what they felt counted, and not what Margont wanted. It was one of the main reasons that he had later become a fervent follower of the republican cause. Because the Revolution considerably reinforced the rights of the individual. To be able to be true to himself was, in the final analysis, all that he wanted. Was that not all that Luise and Relmyer were after too? But in order to do that, they had first to track down this man.

In his mind his childhood memories constituted a sort of monster. A monster taking up too much space in his consciousness, bloated from having gorged itself on dark emotions, on rage, sadness, abandon, hate and dismay. Margont knew that he would never succeed in striking it down definitively. But he wanted to subdue it, to bridle it and tie it up somewhere, as if it were a frisky horse that, once tied up in its paddock, could not harm anyone.

You could not change your past, but you could change the way you thought about it. Should Margont succeed in helping Luise and Relmyer overcome their pasts, he would fortify himself and consign his own beast to a corner of his mind. At least, that was what he hoped. That was also the reason that victims helped other victims.

Lefine was right on two points, in fact. Margont was in love with Luise. However, something was preventing him from drawing close to her, from trying to seduce her: it was their respective pasts and Relmyer’s. Standing between Margont and Luise there were three monsters that he was wrestling with.

Lefine went over to the riverbank, intrigued.

‘What on earth is that fish?’

Across the water glided a boat equipped with three light cannon and propelled by twenty rowers.

The Emperor has decided to have a flotilla patrol the river and harass the enemy observation posts,’ replied Margont. ‘He’s also using small boats to intercept anything that could damage the

bridges. And he’s manned I don’t know how many islands with soldiers and batteries, even those up beside Vienna. So now no one will be able to tell where his army will pop from for the big battle. He’s having reinforcements rushed in from all over the Empire, he’s undertaking reviews ... In short he’s being incredibly active while the Austrians are just waiting.’

They’re not just waiting, they’re digging in,’ corrected Lefine, a proponent of defensive war methods, since war was less bloody for defenders than assailants.

‘Prince Eugene’s Italian army is going to confront the Austrians under Archduke John again. If Eugene wins, he will come to back us up and Napoleon will probably launch his offensive. The situation is endlessly evolving, time is pressing and we, we are stuck here, slouching in the sun, without any ideas! It’s already 8 June!’ ‘Why don’t you go and search the archives with Relmyer then?’ ‘That would achieve nothing! In any case, I can’t read German very well, so to try to decipher illegible writing when I don’t know what I’m looking for...’

Four hussars appeared from behind some trees – an adjutant of the 9th, two troopers from the élite company of the 7th and a young sabreur of the 5th. The variety of their uniforms made an iridescence of colour animating the gliding motion of their horses. They were like exotic birds, combining the colourful plumage of robins with the ferocity of birds of prey.

The men approached Margont. The sun played on their gold braid. ‘Would you by any chance be Captain Margont?’ enquired the adjutant with extreme courtesy, too much courtesy.

His rosy lips and his moustache with the curled tips might have made him look rather ridiculous, but any hint of a smile, and you would find yourself challenged to a duel.

‘I am. And whom do I have the honour of addressing?’

‘Adjutant Grendet. And this is Warrant Officer Cauchoit, Trumpeter Sibot and Hussar Lasse.’

The face of the warrant officer was extremely scarred. The surface of his skin was like a fencing manual. Sabre fencing, of course; for him that was all that counted. He owned two sabres, one very

curved, like a Mameluke’s weapon, and the other almost straight. He looked disdainfully at Margont’s sword. The adjutant went on in the same unctuous, honeyed tone.

‘We have been looking for Lieutenant Relmyer, of the 8th Hussars, for several days. They call him the Wasp sometimes, or the little lieutenant because of his youth and childish countenance. But of course you know exactly to whom I’m referring ... Very unfortunately he is never to be found with his regiment. However, I am told that you know him. Can you tell me where we would be able to find him?’

Margont was an excellent liar. He could thank Lefine for advice on the best techniques.

‘I’ve known Relmyer for only a few days and I don’t know where he could have gone. May I ask why you are looking for him?’

‘It’s very annoying,’ lamented the adjutant. ‘We would be so happy if we could speak to him.’

At these words the trumpeter burst out laughing.

‘Speak to him about...?’ persisted Margont.

‘Well, you see, Captain, Relmyer wounded Lieutenant Piquebois. Yet Lieutenant Piquebois is a very fine swordsman. So we would like to know if Relmyer would agree to show us his technique.’ Margont was outraged. ‘You want to challenge Relmyer to four duels?’

The adjutant shrugged to indicate his disappointment. It did not surprise him that Margont did not understand. He had always considered that foot soldiers and cavalry belonged to different worlds.

‘We don’t fight duels, Monsieur Infantry Officer; we make art! Very well, we’ll be on our way. Tell your friend Relmyer that we’re looking for him. He will easily find us in our respective regiments. Explain that I would be very much obliged if he would respect the order of hierarchy in his encounters with us. The highest in rank first, of course.’

The warrant officer was last to leave. Just before he did so he threw out: ‘Please say hello to Antoine Piquebois for me.’

His finger traced the length of one of his scars, running diagonally

through the chequered pattern of the welts. Margont suddenly remembered him. In 1804, Piquebois, then a hussar, had floored him with a sabre stroke. Officially it had been recorded as a training accident ...

After the hussars had gone, Lefine announced: Tm going to try not to get too close to Relmyer. That way I won’t be too grief-stricken when they bury him in two or three weeks’ time ... because even if he succeeds in knocking off those four strapping fellows, there will be more, and still more. For Antoine, all that calmed down after he was wounded at Austerlitz, because he changed completely after that. He’s no longer a swashbuckler ready to fight at the slightest challenge. Except when he sees Relmyer! But Relmyer, he does everything to attract the calamity that is duellists!’

‘He doesn’t mean to. He has only one idea in his head: to find the man he’s looking for. Look how little he takes Luise’s feelings into account, even though he regards her as his sister. And that fortune that he spent to be able to examine the archives at the

Kriegsministerium. Imagine what else he could have done with all that money? No, he attracts death without even being aware of it.’ Lefine was appalled at this.

The problem is that death is blind,’ he declared. ‘It’s stalking Relmyer but it could just as easily get us by mistake!’

‘Relmyer is tied to his past. He won’t really start to live until he has broken the ties.’

‘There are other ways of freeing yourself from a rope than tugging to make the bulldog attached to it come and bite you.’

‘He only knows how to do it his way.’

‘Listen, about that dog ...’

Pagin galloped over to them. As he felt he was not getting there fast enough – the world turned too slowly for his liking – he was gesticulating. That would have saved time had anyone understood what his waving arm signified. He brought his sweating horse abruptly to a halt, causing it to whinny.

‘Captain, Sergeant: Lieutenant Relmyer wants you to know that he’s found what he’s looking for in the registers. He’s going to try to find the person concerned. If you want to go with him, you will have to follow me immediately.’