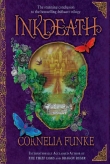

Текст книги "Within These Walls"

Автор книги: Ania Ahlborn

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

2

Thursday, February 4, 1982

One Year, One Month, and Ten Days Before the Sacrament

THE KNOCK ON the door had Audra’s attention drifting from the TV to the front door of her father’s defunct summer property. She couldn’t remember the last time her parents had visited Pier Pointe, but that suited her just fine. It meant that visitors were few and far between. Knocks on the door were rare, which was what had her furrowing her brow at the sound. She abandoned her midafternoon rerun marathon, rose from the couch, and padded across the loose pile of the shag rug toward the front double door. Peeking through the peephole, she caught sight of Maggie’s cropped haircut.

“What are you doing out here?” Audra asked, opening one of the two leaves of the door. Maggie ducked inside without an invitation, her parka beaded with the cold drizzle of coastal rain.

“Came for a visit.” Maggie shook water off her sleeves and onto the redbrick floor of the entryway. “I haven’t seen you in a few days, so, you know, just figured I’d check in, make sure everything was okay.”

Audra offered her only friend a light smile of thanks. It was the little things—like an unexpected visit on a rainy afternoon—that made Audra count her blessings for living less than a mile from Marguerite James; though, she never went by Marguerite, but by Maggie. It was a name she claimed suited her better than the stuffy moniker on her birth certificate. Maggie had a sixth sense. She always seemed to know when to drop in or give Audra a ring, was always intuitive of when to invite her over for dinner or drag her out of the house to wander the shops of Pier Pointe. Most times, Audra resisted the invitations, but Maggie wasn’t one to be easily swayed.

“Everything’s fine.” Audra shut the door against the bluster of wind before following Maggie into the living room. Shadow, her German shepherd, lazily lifted his head from the arm of the couch to regard their visitor, smacked his chops, and went back to his nap. “Did you . . .” Audra paused, peering at Maggie’s damp Audrey Hepburn–style hair. “Did you walk here?”

“Had to get out of the house.” She shrugged, dismissing the weather.

“Where’s Eloise?”

“Day care.” Approaching the couch, Maggie laid a hand atop Shadow’s head.

“Since when?”

“Since this past Monday. Too much time in the house, not enough time with other kids. The same could be said of you, you know. Are you really watching I Dream of Jeannie?”

“What’s wrong with I Dream of Jeannie?” Audra coiled her arms across the sweater that hung limp and oversized from her petite frame. Maggie gave her a look, then shook her head in a motherly sort of way that, had Audra’s own mother possessed a matronly bone in her body, she may have resented. But her mom had filled out an absentee ballot after completing Audra’s birth certificate, resolving to be a Seattle socialite rather than a doting parent. Audra wouldn’t admit it, but she liked being looked after. It was nice to know that someone cared about how she was, what she was doing, whether she was eating, and whether she was taking her pills.

“When was the last time you went outside?” Maggie looked away from the TV and leveled her gaze on Audra’s face. “You look pale. I don’t like it.”

Audra lifted her shoulders to her ears, feigning amnesia. It could have been yesterday. It could have been two weeks ago.

Maggie frowned. “Okay,” she said, her tone resolute. “Get dressed.”

“For what?”

“For a walk.”

“A walk?” Audra nearly laughed. “You do realize it’s raining, right? Just because you’re a crackpot . . .”

Maggie’s expression went stern. Audra suggesting Maggie was nuts was like an alligator accusing a crocodile of having too many teeth.

“It’s just a drizzle,” Maggie insisted, holding firm. “Besides, it’ll do both you and Shadow some good. Look at him.” Shadow rolled his big eyes back and forth between them without lifting his head. “The poor thing is listless. He needs to get out, run around.”

Audra shut her eyes and exhaled a slow breath. She didn’t want to go outside, didn’t want to walk in the rain, but Maggie was right. She’d spent too much time cooped up. If she wasn’t going to give in for Maggie, she at least had to surrender for the sake of her dog.

“Audra . . .”

“Fine, fine.” Audra held up her hands, not wanting to be nagged. “Just let me get changed and we’ll go.”

Apparently satisfied, Maggie sat down next to Shadow on the couch to wait. All the while, Jeannie blinked and nodded her head while waiting for Major Tony Nelson to come home; a perfect life, nothing short of a magic trick.

· · ·

The beach was cold. Audra gritted her teeth against the wind, the hood of her parka cinched so tight around her face it was a wonder she could see the coast. “This is stupid,” she mumbled to herself, her sneakers sinking into the damp sand with each labored step. “Stupid, stupid, stupid.” Audra loved Maggie, but she hadn’t moved to Pier Pointe to take romantic midwinter walks along the shore.

Her father had nearly forbidden the move. Not in your condition, he had said. You’ve got a doctor here in the city. Pier Pointe is too small; you’ll never find a qualified physician there. Except that she actually had, and Congressman Terry Snow had given up the fight and ponied up the keys to the family’s abandoned coastal home. That had been two years ago—seven hundred and thirty days—and she was able to count the number of times her oh-so-worried father had called on a single hand. She’d spoken to her mother even less, but it was for the best. Congressmen weren’t supposed to father manic children. It was bad for his reelection campaign.

Shadow let out a series of barks and Audra looked up from the sand. There, in the distance, a group of four people were milling about a bonfire that had managed to stay lit despite the drizzling rain. A pair of red tents were staked into the sand, shivering in the wind. She pictured the tents taking flight, bursting into flame as they soared across the dancing fire. And then they’d drift over the expansive ocean like a couple of burning Kongming lanterns, red and glowing against a steel-gray sky.

“Are they really camping out here?” Audra directed her question toward her friend, but the wind stole her words. Maggie marched ahead while Audra’s steps lagged, leaving her to bring up the rear of their trio. By the time she picked up the pace to catch up to her friend, Shadow had reached the group in his mad dash across the beach.

When she finally reached the campsite, three pretty girls were rubbing Shadow’s ears, cooing over how cute he was. Maggie was sitting near the bonfire, as though she’d been there all afternoon rather than the sixty seconds it took Audra to catch up. Maggie was always one to quickly take to strangers, but this particular instance struck Audra as a world record. Maggie looked leisurely as she shared a joint with a guy who appeared like a young Tom Selleck. His hair whipped wild in the wind. And while his face and hands and clothes were clean, he immediately struck Audra as a true child of the earth.

The man rose to his feet and extended a hand in greeting.

“Welcome,” he said. “I’m Deacon. Come, sit with us.” Audra’s gaze drifted to Maggie, unsure, searching for approval while simultaneously scrutinizing her friend’s overly comfortable posture. Crowds made Audra uncomfortable. Strangers made her anxious. Maggie, on the other hand, looked as though she’d met this odd assembly of nomads before.

Deacon continued to stand, waiting for Audra to take his place around the fire. Neither Deacon nor the three girls with him wore much to protect themselves against the cold or rain. Deacon’s cowboy boots were half-buried in the sand. The mother-of-pearl snaps on his Western-style shirt glinted in the pale gray of the afternoon. The girls wore ankle-length skirts in a riot of colors—hues more suited for sunshine than rain. And yet none of the four seemed to mind the drizzle or the cold, as though inviting purification. The Washington sky offered a divine sort of baptism.

Audra reluctantly took Deacon’s hand, releasing it a moment later to pull her parka even tighter around herself. Maggie rose halfway from where she sat, seized Audra by the arm, and tugged her down to the piece of driftwood by the fire. There was no getting away. Maggie quickly made her insistence known.

“This is Audra,” she said, offering an introduction when Audra failed to do so herself. “She’s a little shy.”

“Welcome, Audra,” the three skirted girls greeted in unison.

“Yes, welcome,” Deacon said, kneeling on the sand beside his two newfound friends. “There’s no need to be shy,” he assured them. “We’re all family here.”

Family, Audra thought. If you only knew about mine, you wouldn’t say that with such benevolence.

“Are you guys camping? In this?” She motioned to nothing in particular, calling up the wind and the rain and the misery of it all.

“Not camping so much as traveling,” Deacon said. “We’ve been moving up the Pacific coast for a few months now; started down in L.A.” He paused, as if recalling the memory of the first few days of their trip. “I think the weather may have been nicer in California.” Deacon cracked a good-natured smile. Audra couldn’t help but to smile at him in return.

“Are you from there?” she asked. “California?”

Deacon dipped his head down in a thoughtful nod. “I’m from Calabasas,” he said. “You know it?” He spoke to them both, but he focused his attention on Audra, not Maggie. Deacon’s attentiveness unspooled a sense of nervousness inside her chest, the sensation accompanied by an undeniable thrill. Audra and Maggie didn’t go out together much, but whenever Maggie did manage to talk Audra out of the house she stole the spotlight with her bubbly personality and her classic beauty. It seemed that Maggie was set on epitomizing the likes of Mia Farrow with her pretty clothes and her perfect makeup. But Audra felt awkward with her stringy yellow hair and her dumpy, stretched-out sweaters. Not that she couldn’t be pretty—she had plenty of summer dresses crammed in her closet and a vanity packed with everything from hair products to fake eyelashes. The difference between her and Maggie was that Audra didn’t feel pretty, and why should she? The cross-hatching of scars up and down her arms was a constant reminder of her weakness; her parents’ disinterest, an assurance of her insignificance. Audra Snow was used to feeling inconsequential, but now, here was a man who was speaking to her and her alone, as though Maggie wasn’t there at all. And for once, odd as it was, Maggie wasn’t showboating to steal the attention away.

Audra shook her head in response to Deacon’s question. She had heard of Calabasas, but she’d never been to California. Though it would have been nice to walk along the Santa Monica Pier and ride the Ferris wheel, play arcade games, and pretend everything was perfect, even if it was only for a single sunny day.

“It’s close to where they shoot all the pictures,” Deacon said. “You like movies?” Audra nodded. She loved movies, and she especially loved the way Deacon kept his eyes fixed on hers. It was as though he was genuinely interested, as if she was the only one who existed on that beach, the one he’d traveled up the coast hoping to find.

3

Saturday, February 6, 1982

One Year, One Month, and Eight Days Before the Sacrament

AUDRA HAD NEVER been the outdoorsy type. Even as a child growing up in Seattle, she preferred to stay in her room than to play out on the preened back lawn or explore the rivers and trees of the Cascade Range. In her mind, people who enjoyed being out in nature were at peace with feeling small, but for her, being swallowed by the Washington forests was a terrifying prospect. Standing on the shore only to stare out at an endless expanse of ocean made her feel even smaller than she already imagined herself to be. The only peace she found in the water or trees was the lingering thought that Mother Nature could take her if only Audra allowed it. The forest would bury her if she lay down for long enough. The ocean would pull her under if she didn’t fight the current, if she breathed in the water the way she so effortlessly did the air.

And yet, late that morning, she found herself pacing the length of the kitchen, back and forth across the linoleum. Her gaze occasionally flicked up to the window above the sink, casting a glance onto the overgrown cherry orchard just beyond the glass. It had been two days since she and Maggie had taken their walk on the beach, forty-eight hours since she had met the charismatic mystery man who had made her feel a little less invisible than usual.

Now, the beach was calling her back. She needed to see the ocean. The sand. Those tents.

Back and forth she went, from the refrigerator to the stove. Shadow watched her from the mouth of the kitchen, his tail giving her a hopeful wag every time their eyes met.

You know you want to, he panted. It isn’t raining. We could go check, just give a peek down the coastline to see if they’re still there.

Audra paused her pacing, her gaze fixed on her dog’s furry face.

“What is it?” she asked him. “You want to go out?”

Shadow sucked his bobbing tongue into his mouth. His ears perked at the suggestion, but he didn’t move from where he sat.

“You want to go to the beach?”

He stood up, his tail flicking left and right.

“You . . . want to go see if Deacon is still there?”

Shadow snorted, excited by a prospect Audra knew he didn’t understand. He bowed into a quite literal downward dog, his butt held high in the air.

“But it’ll be weird if we just show up,” she murmured, lifting a hand to chew on a nail. “Maybe I should call Maggie.”

Shadow barked. Forget Maggie.

She raised an eyebrow at his insistence.

What do you need Maggie for? You’ve got me.

“You’re right.” She let her arms drop to her sides. “I live here, and you want to go for a walk, don’tcha?” As soon as she uttered Shadow’s trigger word—walk—his eyes went wild. He reared up and bolted out of the kitchen, completed a couple of breakneck doughnuts around the coffee table, and returned to his spot with unbridled anticipation. Audra cracked a smile at his enthusiasm. There really was no choice now. If she backed out, she’d break Shadow’s thumping doggie heart.

She saw the tents as soon as she and Shadow made their way out of the thicket of trees and into the clearing that opened onto the coast. At first she thought she was imagining things, but the charred remains of their bonfire assured her that the tents had moved from where they’d been on Thursday afternoon. They were closer now, as if inching their way toward her home.

Shadow made a run for the tents. When he nudged his snout inside one of them, she sucked in a breath to yell for him to come back. Before she could find her voice, Deacon’s head popped out of the flap. He clambered out and then strolled toward her with a wide smile across his face.

“Audra!” He caught her in a tight hug as soon as he was able to reach her. “We were wondering when we’d see you again.”

You were? The question was poised on her tongue, but she held it back.

“Come,” he said, motioning for her to follow him despite not giving her much choice. Without asking whether she’d like to join him, he looped his arm through hers and pulled her along. By the time they reached the new campsite, the girls who had fussed over Shadow on Audra’s previous visit had crawled out of Deacon’s tent. “I want you to meet everyone,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, there are nine of us,” he explained.

Nine? Audra gaped at the number. How can nine people fit into two tents? And how was she going to handle meeting them all without Maggie there to help her through it, to take the edge off, if only by stealing away some of the undivided attention?

“I . . . I was just taking Shadow for a walk,” she stammered, anxiety crawling up her throat. “We can’t stay. He just needed to go out.”

But Deacon wasn’t listening. He released his hold on Audra’s arm and called into the first tent. “We have a visitor,” he announced to no one and everyone. “Come out, come out. Meet our new sister.”

Audra caught her bottom lip between her teeth as people began to surface from behind red nylon. They reminded her of circus clowns piling out of a tiny car, one after the other, a seemingly endless stream. The second tent remained zipped against the cold.

Deacon introduced his family one by one. There was Noah, who had the biggest eyes Audra had ever seen, larger than a pair of blue Jupiters. The three girls who had previously made Shadow’s acquaintance were Lily, Robin, and Sunnie with an ie. Lily was tall, slender, and regal with her milk-white skin, which looked impossibly pale next to her blazing red hair. Robin was more of a girl-next-door, and Sunnie looked so young Audra pegged her to be fifteen at the absolute oldest. Her hair looked as though she’d chopped it short with a pair of dull kitchen shears. Kenzie was hyperkinetic, unable to stand still for more than a few seconds. And while Audra assumed it was just his personality, she couldn’t help but wonder if he had some sort of disorder. It was possible he was coming off a bad trip. They certainly struck her as hippies, a throwback to the love fest of the sixties, complete with tabs of acid and daisies woven through their hair.

But counting Deacon, that was only six who had come out of a single tent. That meant three people remained in the second, and it didn’t look as though they had any intention of introducing themselves anytime soon. Deacon noticed Audra counting heads and gave the second tent a nod.

“Gypsy and Clover keep to themselves,” he explained. “But you’ll meet them soon enough. And then there’s Jeff . . .” The entire group seemed to coo when Deacon uttered the name.

“The angel,” Lily murmured through wind-whipped hair.

“He’s our protector,” Sunnie said, her young face wistful, as though the mere thought of their absentee leader insulated her from the chill.

Audra pinched her eyebrows together and took a single step back. It was probably nothing, but she couldn’t help her rising discomfort just the same. The girls looked distant, as though their very thoughts were far away. Noah’s wide eyes gave her the creeps. He was staring at her, his expression vacant despite the smile on his face. Kenzie bounced from foot to foot, frenetic. For half a second she was sure he was going to make a break for her, his arms outstretched, his eyes wide and glazed over like something out of a George Romero flick. Looping her fingers beneath Shadow’s collar, she gave Deacon an apologetic shrug.

“So, um . . . I’ve got to go,” she told him. “It was nice meeting you all.”

“I’ll walk with you,” Deacon told her. She wanted to go alone, to leave them all behind if only to regain her bearings. But she couldn’t very well deny Deacon’s offer. There was something off about the others, something that made her skin crawl. Their talk of angels and protectors was off-putting. But Deacon still struck her as cool. He was, after all, the reason she had bundled up and battled the cold all on her own, and there was something to be said for that. He had managed to get Audra out of the house without even asking while, after two years of friendship, Maggie still had to beg.

They didn’t speak for a long while, walking shoulder to shoulder along the beach with Shadow ahead of them. But just when she was sure their walk would be a silent one, Deacon said:

“Do you live alone?”

She blinked at the question.

“Um . . .” Hesitation. She considered lying, if only to not appear as vulnerable as she truly was.

“It’s all right,” he said. “We all need to be alone at points in our lives. Silence leads to self-discovery. Are you spiritual, Audra?”

That was the last thing she had expected him to ask. “I don’t attend church,” she said, “if that’s what you mean.”

Deacon laughed and shook his head. “Let me guess: someone forced you to fill a pew when you were a kid?”

“Yeah, something like that.” It was true. All throughout her childhood, her mother had a thing for dragging her out of bed on Sunday mornings. And yet Audra didn’t think of her parents as religious people. The older she grew, the clearer it became: church was for keeping up appearances. Those frilly pink dresses she’d been stuffed into certainly hadn’t been for her benefit.

“Seems like that’s the case for almost everyone,” he said. “But church doesn’t equal faith, you know. The faithful don’t need to be herded beneath steeples to believe. Fire and brimstone is a motivator for those who stray from the path, like children who can’t stay in line. Priests and pastors slap hands out of cookie jars and threaten you with eternal damnation. If you need that to be faithful . . . then your faith is weak.”

“But you need to believe in something to have faith,” she said. “Right?”

“Is that to say you believe in nothing?” he asked. “Surely that can’t be true.”

Audra didn’t respond. Rather, she ducked her head against the cold and focused on the sand beneath her feet. She wasn’t sure she believed in anything but her own solitude, a belief she’d come to terms with before her fourteenth birthday. Two suicide attempts and a mother’s lack of sympathy had been enough to convince her that, one day, she’d die and would be alone when it happened. No purpose. No lasting impact. She’d be the girl nobody had heard from. It would be weeks before someone found her decomposing corpse. Sometimes she wondered who her discoverer would be, hoping it wouldn’t be Maggie with Eloise poised on her hip. Maybe it would be the mailman, fed up with her overstuffed mailbox. Or someone come from the electric company looking to collect. Maybe it would be her father, finally forced back to Pier Pointe after not hearing from her for half a year. Or maybe it would be a pair of Girl Scouts hoping to sell a few boxes of Thin Mints or Do-si-dos.

But deep down, she hoped it would be her mother.

Her mother had found Audra when she had slit her wrists at twelve years old. Susana Clairmont Snow stepped into the bathroom and saw her only child bleeding onto the freshly scrubbed white tile floor. Thick crimson rivulets filled the gutters between each gleaming ceramic square. What have you done?! she screamed, then grabbed up the bath mat and threw it into the tub to save it from ruin rather than calling for help. It had happened ten years ago, but it was one of those moments left hanging in suspended animation, always looming at the back of her mind.

Audra hoped this time around that her mother would bang on the front door to no avail before pulling out the spare key. She hoped Susana would storm in, pissed off, only to find her daughter blue and bloated, gently swinging from one of the living room rafters by a length of clothesline. Audra had already tested the line’s tensile strength a handful of times. She was certain it would hold.

“What are you thinking about?” Deacon asked.

“My mother.”

“Are you two close?”

She wanted to laugh at that, but all she managed was a scowl.

“Maggie said that you’re shy . . .” he said. “But I have to say that you strike me more as lonely.”

Her scowl turned into a glare. She peered at her feet, Deacon’s statement igniting a pang of resentment deep in her gut. She appreciated the company, but he had some goddamned nerve making assumptions, no matter how spot-on they were.

“I’m sorry,” he said, noticing her annoyance. He looped his arm through hers for the second time that afternoon, as if expecting his simple gesture to win her forgiveness.

She nearly pulled away. Lonely, she thought. What the hell do you know about lonely? At least I don’t need to surround myself with people who I call “family” to feel complete.

“I guess it makes me uncomfortable,” he confessed, derailing her inner tirade. “Because I remember living on my own, being lonely myself.”

The way he said it downshifted her irritation into a lower gear. His arm tightened around hers, and the way he looked at her convinced Audra that, despite their not knowing each other well, he was letting her in on a real secret. He wanted her to know him. And if that were true, it meant that this charismatic man wanted to know her, too. But, in exchange, Audra had to make an effort, had to reciprocate, open up.

“When you were talking about California,” she said, “you seemed saddened by the memory, like you missed it.”

His face brightened a little, as though charmed by the fact that she had empathized with him on their very first meeting. His expression fell a moment later though, and he nodded to say she was right. But he contradicted his nod with a denial. “Nah, I don’t miss it. I didn’t have anyone back there, at least no one that really understood who I am. I’ve left that life behind. Now, I don’t have a physical home, which can be pretty rough. But you don’t need a physical home when you’ve got an emotional one. You know what they say about people who surround themselves with material possessions, right?”

Audra shrugged.

“The man with the most possessions is the poorest of all. It’s why I left L.A. If you set eyes on the house I grew up in, you’d fall over right where you stand.”

“What do you mean? What was wrong with the house?”

“Nothing, and everything. You know those houses you see on TV shows with the motorized front gates? The bars are a metaphor. You can go in and out, but every night you’re sleeping behind them like a prisoner in a cell.” He paused, readjusted his grip on her arm. “My old man is a movie producer. He works on films with guys like Jack Nicholson and Robert Redford.” Audra gawked at him, and Deacon grinned at her piqued interest before continuing on. “You know Faye Dunaway?”

“Sure, who doesn’t?”

“She came over for brunch a few times. She and my mother smoked cigarettes on the patio while discussing the pros and cons of wicker furniture. Thankfully, this was before she did Mommie Dearest. Because at ten or eleven years old, I would have shit my pants had I known Joan Crawford was milling around our pool.” He made crazy eyes at her, and Audra couldn’t help but laugh.

“I wouldn’t have guessed,” she said.

“Guessed what? That I come from money?”

She nodded. Deacon looked more like a Texas Ranger than the son of a bigwig Hollywood producer.

“Well, good,” he said. “If you can’t tell, that means I’ve successfully wiped that part of my life away. You know, in a way, Mommie Dearest is a pretty good analogy for the lives we were forced to lead.” His statement was unflinching, as though he knew Audra came from the same place as him—a big house, absent parents. It was another correct assumption, one that led her to believe that she wasn’t as closed off as she had thought. He was reading her like one of his father’s screenplays. “Not all of us were beaten with wire hangers, but psychologically . . . emotionally?”

She nodded again, understanding what he was getting at.

“But you let that go, Audra. What’s in the past is in the past. Those people, your parents, they don’t have to matter. They only matter if you give them that power. Take back your life, take back control. You put your foot down and tell them ‘I’m worth something, worth more than your fuckin’ money, Pops. I’m worth more than your most precious jewels, Mommy dear.’ ”

Her heart fluttered inside her chest. She couldn’t tell if it was love or nerves. She dared to shoot a glance at him, and their eyes met as they approached the clearing that would lead her back to her parents’ home. It was as though he knew everything about her, knew just what she needed to hear.

“You understand what I’m saying,” he said. “I can see it.”

She looked away, nervous. “See what?” That he had her all figured out? That the longer he talked, the more she wanted to drag him upstairs and into her bedroom, lay herself out for him, and let him swallow her whole? If she took the power away from her parents, she may as well let the mystery man beside her have it instead.

“You and I are really alike,” Deacon said. “Our parents come from the same tribe—the rich, the avoidant. And Jeff, he’s like us, too. His folks . . .” Deacon shook his head. He had no words for Jeff’s parents. “They grew him the way one would grow a tree, and then they chopped him down. Whoever made up that crap about blood being thicker than water didn’t have a clue, and that’s where we come in.” He motioned to the camp behind them. “You can’t pick your blood family, but you can pick your spiritual one. Spiritual, not religious. Spiritual on the plane of mutual understanding, shared hopes, communal faith. Once you find the people you’re meant to be with . . .” He shook his head as if to say that he couldn’t describe the ecstasy of such a discovery.

“Is that what they are?” Audra’s tone was quiet, her gaze still diverted. “Your spiritual family?”

“I love them as much as if they’d come from my own rib.” Sliding his arm out from around hers, his hands drifted to rest upon her shoulders. “You don’t have to be alone,” he told her. “Don’t you see? Us meeting like this, it’s fate.”

Fate.

“Our past lives are nothing but darkness,” he said. “That’s why we have to leave those people and those memories behind. It’s like being stuck in a coal mine for half of your life. If you live in the darkness of your past for long enough, it makes you blind. You won’t be able to recognize enlightenment when it’s right in front of you. But I know it when I see it . . . and I see it in you.”

“See what?” She pressed her lips together in an anxious line.

“You’re ready,” he told her. “It’s time to open your eyes.”