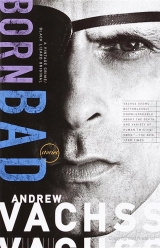

Текст книги "Born Bad: Collected Stories"

Автор книги: Andrew Vachss

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

Warrior

The Golden Boy was black. Twenty–one and 0, with seventeen KOs. He was as sleek as an otter—all smooth, rubbery muscle under glistening chocolate skin. He wore royal purple trunks with a white stripe under an ankle–length robe in matching colors, his name blazing across the back: Cleophus "Cobra" Carr.

Tonight he was the main event, a ten–rounder. Middleweights, they were supposed to be, but they called Carr's weight out at one sixty–four.

There was a lot of betting in the mid–priced seats just past ringside—betting how long the fight would go before Carr stopped the other guy.

Nobody knew the opponent—he was the last–minute replacement for the guy Carr was supposed to fight. He walked to the ring by himself, wearing a thin white terry–cloth robe. His trunks were black.

The announcer pointed to the opponent's corner first. Manuel Ortiz. Dragging the last name out way past two syllables—Orrrr–Teeese! Ortiz was fifty–six and sixteen, with thirty–two KOs. Originally a welterweight, he'd go up or down…wherever there was work. They had him at one fifty–nine tonight.

Maybe he had dreams for this once—now it was a part–time job.

I knew his story like it was printed in a book. He got the call the day before, finished his shift at the car wash, got on the Greyhound and rode until he got to the arena—I could see it in his face, all of that.

Carr was twenty–two. He'd gone all the way to the finals at the Olympic Trials before turning pro two years ago. They said Ortiz was thirty, shading it at least a half dozen. The guy who managed him worked out of a phone booth in a gym somewhere near the Cal–Mex border. His boxers always gave good value—they wouldn't go down easy, didn't quit, played their role.

The fighters stepped to the center of the ring for their instructions. Carr had three men standing with him, one to each side, the third gently kneading the muscles at the back of the middleweight's neck. Ortiz stood alone—the cornerman they supplied him with stayed outside the ring, bored.

Carr gave Ortiz a gunfighter's stare. Ortiz never met his eyes. That was for younger men—Ortiz was working. I could feel the Pachuco cross tattoo under the glove on his right hand….I knew it would be there.

The referee nodded to the fighters. Ortiz held out his gloves, just doing as he was told. Carr slammed his right fist down against them. The crowd cheered, starting early.

The bell sounded. Carr snake–hipped out of his corner, Bring a quick series of jackhammer jabs. Ortiz walked forward like a man in slow motion, catching the jabs on his gloves and forearms, pressing.

Carr danced out of his way, grinning. I dropped my eyes to the canvas, watching parallel as Carr's white leather boxing shoes ice–skated over the ring, purple tassels bouncing as Ortiz's black lace–ups plodded in pursuit.

Deep into the first round, Ortiz hadn't landed more than a half–dozen punches. He kept swarming forward, smothering Carr's crisp shots, his face a mask of patience. Suddenly, Carr stopped back–pedaling, stepped to the side, hooked off his jab and followed with a smoking right cross, catching Ortiz on the lower jaw. Ortiz shook his head—then he stifled the crowd's cheers with a left hook to Carr's ribs.

The bell sounded. Carr raised his hands, took a quick lap around the ring, like he'd already won. Ortiz walked over and sat on his stool. His cornerman held out his hand to take the mouthpiece, splashed some water in the fighter's face, leaned close to say something. Ortiz didn't change expression, looking straight ahead—maybe the cornerman didn't speak Spanish.

Over in Carr's corner, all three of his people were talking at once. Carr was grinning.

A girl in a gold bikini wiggled the perimeter, holding up the round–number card. The crowd applauded. She blew a kiss.

Carr was off his stool before the bell sounded, already gliding across the ring. Ortiz stepped toward Carr, as excited as a gardener. Carr drove him against the ropes, firing with both hands, overdosing on the crowd's adrenaline. Ortiz unleashed the left hook to the body again. Carr stepped back, drew a breath, and came on again, working close. Ortiz launched a short uppercut. Carr's head snapped back. Ortiz bulled his way forward, throwing short, clubbing blows. Carr grabbed him, clutching the other fighter close, smothering the punches. The referee broke them.

Carr stepped away, flicking his jab, using his feet. The crowd applauded.

The ring girl put something extra into her wiggle between the rounds, probably figuring it was her last chance to strut her stuff.

Halfway through the next round, the crowd was getting impatient—they came to see Carr extend his KO record, not watch a mismatch crawling to a decision.

"Shoeshine, Cleo!" a caramel–colored woman in a big white hat screamed. As though tuned in to her voice, Carr cranked it up, unleashing a rapid–fire eight–punch combo. The crowd went wild. Carr stepped back to admire his handiwork. And Ortiz walked forward.

By the sixth round, Carr was a mile ahead. He would dance until Ortiz caught him, then use his superior hand speed to flash his way free, scoring all the while. When he went back to his corner at the bell, the crowd roared its displeasure—this wasn't what they came to see.

A slashing right hand opened a cut over Ortiz's eye to start the next round. An accidental head–butt halfway through turned the cut into a river. The referee brought him over to the ring apron. The house doctor took a look, signaled he could go on. The crowd screamed, finally getting its money's worth.

Carr snapped at the cut like a terrier with a rat. Ortiz kept playing his role.

Between rounds, Carr's handlers yelled into both his ears, urging him to go and get it. Ortiz's cornerman sponged his cut, covered it with Vaseline.

The ring girl was really energized now, hips pumping harder than Carr was hitting.

Carr came out to finish it, driving Ortiz to the ropes, firing a quick burst of unanswered punches. Ortiz came back with his trademark left hook, but Carr was too wired to get off–tracked, smelling the end. A right hand landed Hush on Ortiz's nose, a bubble–burst of blood. Ortiz spit out his mouthpiece, hauled in a ragged breath and rallied with both hands. A quick look of surprise crossed Carr's face. He stepped back, measuring. Ortiz waved him in. Carr took the challenge, supercharged now, doubling up with each hand, piston–punching. Ortiz's face was all bone and blood.

The referee jumped in and stopped it, wrapping his arms around Ortiz.

Carr took a lap around the ring, waving to the crowd.

Ortiz walked over and sat on his stool.

The announcer grabbed the microphone. "Ladies and gentleman! The referee has stopped this contest at two minutes and thirty–three seconds of the eighth round. The winner by TKO, and still undefeated…Cleophus…Cobra…Caaaarrrr!"

The crowd stood and applauded. Carr did a back flip in the center of the ring.

Ortiz's cornerman draped the white robe over the fighter's shoulders.

Ortiz walked back to the dressing room alone.

"That's a real warrior," Frankie said to me.

"Carry He's nothing but a —"

"Not him," Frankie said. "The Spanish guy."

That's when I knew for sure that Frankie was a fighter.

White Alligator

The alligators were tiny, perfectly–fanned predators. They shone a ghostly white in the swampy darkness of the big tank.

"You never saw white ones before, did you?" The curator was a plump young woman, thick glossy hair piled carelessly on top of her head, soft tendrils curling on her cheeks. Wearing a white smock, no rings on her fingers, nails square–cut. A pretty, bouncy woman, full of life, in love with her work.

I shook my head, waiting. I hate this part of the business. They always have a reason for what they want done—I don't need to hear it.

"Actually, white alligators aren't all that rare. It's just that when they're born in the wild, they don't have much chance of survival. A grown alligator is a fearsome thing—it really has no natural enemies. But the mother alligators don't protect the babies once the eggs hatch. One old legend sap that a baby alligator who actually manages to survive all its enemies and grow to full size spends the rest of its life getting even. That's why they're so dangerous to man."

I nodded again.

"You don't talk much, do you?"

"That's part of the service," I said. Catching her dark eyes, letting her feel the edges of the chill.

We walked past the bear pit. Grizzlies, Kodiaks, brown bears, black bears, all kinds. But the polar bear was in a separate area just around a sharp corner in the path. Prowling in circles, watching.

"How come the polar bear can't be with the others? He needs colder water or something?"

"She. That's a mama bear. Polar bears are solid animals. They don't mix well. And when they have cubs, they attack anything that approaches."

"Show me where it's been happening."

We strolled over to the African Plains enclosure. Somebody had been sneaking into the zoo at night. It started with stoning a herd of deer. Then they shot one of the impalas with a crossbow. The animals didn't die. Whoever did it came back again. And a cape buffalo lost an eye.

"It's just a matter of time before he kills one of our animals," the curator said.

"He doesn't want to kill them. He wants them to hurt. Wants to hear them scream."

White dots blossomed on her cheeks. "How do you know?"

"I know them."

"Them?"

"Humans who do this."

Her hands were shaking.

"Nature can be hard, but it's never cruel. Survival of the fittest—that's how a species grows and protects itself. But animals never kill for fun."

"Neither do I," I said. Reminding her.

She reached in her pocketbook and handed me a thick envelope. "This is my own money. I couldn't go to the Board for help. They tried hiring security guards, but it kept happening. I can't have the animals tortured like this."

"I'll take care of it."

She fumbled in her purse. "You'll need a key. To get in after dark."

I waved it away. "Whoever's doing this didn't need a key."

The curator took a deep breath. Making up her mind, getting it under control. "I believe there have to be laws. Nature has its laws, we're supposed to have ours, too. But I don't want—I mean, you promised."

"I told you the truth," I said….

He didn't come until the fourth night. I was waiting in the shadows cast by the Reptile House. The African Plains enclosure was to my left, the bear pits just past that. He was wearing sneakers, but the animals let me know he was coming. Restless stirring. A nightbird screamed.

I circled behind him to the bear pit. As soon as he walked past, I took the five cans of industrial–strength Teflon spray out of my pack and went to work. It wouldn't last more than a half hour—the concrete absorbs it real fast.

When I caught up with him again, he was standing at the fence, watching the herd of antelope, picking a target. Wearing some store–bought ninja outfit. Stalking, he thought.

I stepped out of the dark, the pistol in my hand. He didn't turn around.

"Drop the toy, punk," I whispered, giving him a choice.

It fell from his hands.

"Hands up," I said, calm and quiet, moving closer.

"Wha—what do you want?"

"What do I want? I want you. I've been waiting for you, maggot. We're going to take a little ride. To a nice hospital. Where they'll talk to you, boy. Maybe find out what else you've been doing when it gets dark. Understand?"

Standing maybe fifteen feet away. Giving him another choice.

"No!" he screamed, tuning and running from me, sneakers slapping hard on the concrete.

I chased after him, letting him feel me coming. He was doing fine until he got to the curve just before the pit where the polar bear guarded her cubs.

Maybe he screamed.

Witch Hunt

1

The first time I heard a message, I couldn't obey. I could hear it, but I was distant from it, the way I am from people talking. They think I can't hear them, but I can–I just can't get close enough to say anything.

The messages don't come from inside my head, no matter what the doctors say.

I was small when I first heard them. I couldn't do anything to stop them. Any of them. The people, I mean, not the messages. I can stop people, sometimes, but I would never stop the messages.

2

No matter how much I screamed, my parents would still leave me with her. They acted like they didn't understand, because I couldn't talk then.

By the time I could

3

Ellen burned me. Just to show me she could do it. My babysitter. She was in charge when my parents would go out. Sometimes she would beat me. Spanking, she called it. She would do it real hard until I would cry. Then she would tell me I was a good boy.

She showed me how to do what she wanted. If I didn't do it, she would hurt me. Sometimes she hurt me anyway. She liked to do it. She would get all sweaty and close her eyes. Later she would laugh.

4

My parents liked her. My mother told my father he only liked her because she wore her blue jeans so tight you could see her panties right through them. My father got all red in the face and said how reliable she was. My mother said how hard it was to get anyone to watch me.

Ellen made me lick her. And she put things inside me too. When I got older, she took pictures of me.

She said if I ever told, they wouldn't believe me. And then she'd get me good the next time.

Cut out my heart and eat it.

Sometimes Ellen wore a mask. Sometimes she burned things that smelled funny.

Her eyes could cut me and make me bleed.

She had a tattoo inside her leg. On the high, fat part where her legs came together. A red tattoo of a cross, like in church. The cross was upside down. Where it would go into the ground, it went inside of her.

5

I told on her. One night, just before my parents were going to go out. I was five years old and I could talk. I was so scared I wet all over myself, but I told.

They looked at each other–I've seen them do that a lot, ever since I started watching them. But when Ellen came over, they told her they weren't going out that night and she could go back to her house.

Ellen looked right at them. Right in the eye. "Is Mark telling his crazy stories again?"

"What stories?" my mother asked her.

"His Devil stories, I call them. He told me his kindergarten teacher was a monster. How she wore this mask and carried fire in her hand. It must be that cable TV. My Dad won't let me watch it."

I could see it happening. I screamed so loud something broke in my eyes. Then I couldn't see anything.

6

They put me in a hospital. A lady came to see me. She was very nice. She smelled nice too. She came a lot of times. Every day.

After a while, I could see again;

I wouldn't talk to the nice lady at first, but she promised me Ellen could never get me. I was safe.

So I told her. I told her everything. She said she would fix it. Everything would be all right.

When they came back a couple of weeks later, they had the nice lady with them. She sat down on the bed next to me and held my hand. She said they looked at Ellen. Without her clothes on. And there was no red tattoo like I said. It must be my imagination, the lady said. She had a sad face when she said it.

I knew it then. She was with Ellen.

I was already screaming when they showed me that first needle.

7

I was in the hospital a long time. Sometimes my parents would come in there with the lady I thought was nice. After I took my pills I would get dreamy. But I wouldn't sleep, not really. Just lie there with my eyes closed and listen to them.

"We could get sued," my father said. "Ellen's father hired a lawyer. He said false allegations happen all the time. A witch hunt, he called it."

It scared me, the way he said it. I didn't look.

8

They tested me, to see if I was stupid. When they found out I wasn't, then they said I was crazy. I had to talk to a doctor. I told him about the messages. He was the first one. He said they came from inside my head. I told him "No!" and he pushed a button and some big men in white coats came in.

Later, they started the drugs. Haldol. Thorazine. All kinds of things. I learned to take the pills. Otherwise, it was the needle.

Some of the attendants, they gave you the needle anyway, even if you were good. They liked to do it. But it was the nurse who gave the orders. She was with Ellen.

9

They let me go home sometimes. My mother would make me take the medication. I got older and older, but it didn't make any difference. I still had to do what they said.

I cost a lot of money. I heard them talking. A lot of money.

"Paranoid schizophrenic," my mother would say. What the doctors told her, like a religion.

Ellen's picture was in the paper. Her father was arrested for having sex with his daughter. A little girl. Nine years old. I was eleven then, and I could read good. Ellen's picture was in the paper because she told on her father.

In the paper, they said Ellen was a hero. For saving her sister.

When I asked my mother about Ellen, she slapped me. Then she started crying. She said it wasn't my fault–I was born this way. I knew she meant the messages. Then she called the hospital and they came and took me away.

10

The medication has side effects. I know what they call it. Tardive dyskinesia. My face jumps around. My whole body twitches. My mouth is so dry and it's like it is stuffed with cotton. My hands shake. I'm dizzy. My stomach is upset. I hate it.

When I stop taking the pills, they give me the needles.

They never catch me not taking the pills. It's just that I act different without them. And they can tell.

Act. That was a message I got all the time. Act!

11

I'm an out-patient now. I live in a room. My parents moved away. I don't know where. I'm an adult now. Twenty-three years old.

I get a check. From the Government. Every month. It comes to where I stay. I pay my room rent. I eat in restaurants, but I don't eat that much. I'm not hungry much.

There is a television set in my room. I always leave it on. Messages come through it for me.

I don't take the medication very often, but I act like I am. Nobody looks that close.

12

They send you cues. That's the message, to watch for the cues. I go out, looking. The subways are the best. There's all kinds of crazy people in the subways. People never look at me that way. I look right. I'm careful.

I look carefully. At everything, I look. There's a third rail. It's death to touch it. If you look down, down into the pit, you can see the other tracks. Water runs between the tracks, like a river. You can see the things people throw there. Sometimes you can see a rat, watching up at the people.

The messages are everywhere, but they are never spoken. Not out loud. They come through things.

You have to watch them from behind because their eyes can burn you.

The first time, in the subway, the train came through the tunnel. Shoving through, too tight for the tunnel, like Ellen did to me. When the train screamed, I knew I was in the right place.

From behind, they look alike unless you look close. If you can see their panties, the outline of their panties, under their skirts or their slacks, then that's them. That's how you know them.

The first time I saw that, the train was screaming in. I was jammed in behind her in the crowd. When I pushed her, she went right under the wheels. Then everybody screamed like the train.

Nobody ever said anything to me.

13

The message comes to me anytime. Especially in my room, where the medication doesn't block the signals. When I hear the message clear, I go out. To do my work.

I'm on a witch hunt.

Working Roots

Shawn knelt at the door to his tiny closet, worshipfully regarding a red shoebox. He slowly removed the lid and carefully removed his prize. Air Jordans, Nike's very best. The Rolls–Royce of sneakers, gleaming in pristine white with artful black accents. He turned one gently in his hands, admiring the intricate pattern of the soles, the huge padded tongue, the plastic window in the heel through which he could see the air cushions. No matter how closely he looked, Shawn could not find a single blemish to mar their perfection.

Almost two hundred dollars for a pair of sneakers. Granny would never understand. All they had to live on was her miserable little Disability check. If Granny wasn't able to make a little extra selling potions and charms to other people in the Projects, they wouldn't make it at all. It got harder and harder to sell her spells every year, Granny told him–younger people just didn't believe in the old ways.

Granny might not understand, Shawn knew, but she would never get mad at him. Old people were supposed to be mean, but Granny never was. She never punished him, even when he deserved it. Other kids got a whipping for nothing at all, sometimes. He'd heard them talk about it, at school.

Yeah, Granny was old, and she was kind of strange. And, sure, there was that back room, where he was never allowed to go. But she was always home, always had food for him. Always eared for him when he was sick or hurt. So maybe they didn't have a color TV like everyone else. Maybe he couldn't play Nintendo, couldn't have his friends over either. He had complained about the old lady's ways to his running partner Rufus one day.

"Shut up, fool!" Rufus replied.

Shawn saw the pain in his best friend's eyes–he felt ashamed again. Granny never got drunk, didn't take drugs, didn't have strange men living with her, different ones all the time. Rufus was right.

Shawn had worked for his special sneakers. Worked hard. There was easy money to be made around the Projects, inside and out. The drug dealers were always looking for new runners, the numbers man could always use a smart kid who could keep records in his head. Stealing and hustling were a way of life…sometimes a way of death, too. Shawn didn't touch any of that. All summer long, he had worked…hauling the monster bundles of newspapers the trucks dropped on the streets at dawn to the individual newsstands. Afternoons, he helped out in a car wash. He didn't spend his money, although the temptations were great….Shawn was fifteen.

Now it was September, and school was starting. Shawn bought his own clothes this year, with the money he'd earned, Granny was proud of him for that, but she didn't know about the sneakers.

When he'd gotten his first money from the newspaper driver, he bought Granny a gold necklace. Twenty dollars, the young man in the long black coat told him…for gen–u–ine eighteen–karat gold. Shawn thought how pretty it would look on Granny. He showed it to Rufus, but his friend said it wasn't gold at all.

"You been hustled, chump. That ain't nothin' but brass…turn green right around your neck."

Shawn gave the necklace to Granny anyway. But because he had been taught not to lie, he told her what Rufus had said.

"Sometimes, people believe thinkin' the worst means they smart. It ain't always so, son," Granny told him. And she told him the necklace was real gold too. Gave him one of her dry kisses.

She always wore the necklace. And it never turned green.

Shawn couldn't really remember a time when he hadn't been with Granny. He knew his mother was dead, killed in a drive–by shooting while she was standing on the corner, just talking with a friend. They never caught the night riders who so casually blew her away. The police told Granny the shooters were really trying for a dope dealer standing on the same corner, like that would comfort her.

There was an "Unk" written in the space for his father's name on his birth certificate. Rufus explained that to him.

"Jus' means yo' momma didn't tell them yo' daddy's name at the hospital, that's all."

"Why wouldn't she tell them?"

"'Cause the Welfare go after him for the support money, see?"

Shawn nodded like he understood, but he was confused. Granny didn't collect Welfare–her Government money came from working all her life. As a maid. In Louisiana, where she was from. Where his Momma was from too, she told him. But Momma had come north when she was only a young girl.

"Came for the party, stayed for the funeral," Granny told him.

Sometimes, people would come to the apartment to see Granny when they had a problem. A lover who jilted them, a job they were hoping to get…stuff like that, Granny always seemed to know what they wanted before they even asked. She would speak a foreign language while she was working…sort of like French, Shawn thought, but he couldn't tell for sure. He knew it wasn't Spanish–he heard that every day in school and this wasn't the same. And she worked with roots. Special roots she got from someplace. Dried old things, all twisted and ugly. But Granny could make things happen with them, folks said. Some folks, anyway.

Other folks, they said she was crazy.

School was tomorrow, and Shawn couldn't decide. His beloved sneakers wouldn't change his status sitting in his closet, but if he wore them outside…there was a risk. The Projects were full of roving ratpack gangs. They'd take your best clothes in a second, leave you bleeding on the ground if you tried to stop them. School was close by, but it was a long, long walk.

"I'm going downstairs to hang out, Granny. You want anything from the store?"

"No, son. Just watch out for yourself, hear?"

"Yes ma'am."

Shawn took the stairs. It was only seven flights, and the elevator scared him. You got trapped in one of the cars, there was no place to go.

He spotted Mr. Bart on the third floor landing. Mr. Bart was a monster of a man, over six and a half feet tall, more than three hundred pounds of muscle. But his mind wasn't right and he could be vicious, rip your head off with one hand, easy as pie. He could never catch anyone, though–his legs didn't work. Mr. Bart supported his huge body with a steel cage that went from his waist all the way to the ground. It had four rubber legs, like a walker. The hospital had to make it up special for him. Mr. Bart would pick it up, stick his arms straight out, slam it down, then swing his legs forward, supporting all his weight on his massive forearms. His hands were the size of telephone books…the Yellow Pages. You could hear him coming a mile away…like an elephant thumping.

"Good evening, Mr. Bart," Shawn called out.

"My money!" the giant grunted, touching a leather bag he had looped over a hook on the front of his walker.

"Sure is, Mr. Bart. Your money."

The monster smiled. Kids were always snatching his little bag, just to be doing it, show how brave they were flirting with disaster. They would grab the bag and run, stand down the corridor and empty it of its few coins, then drop the hag and run away. Mr. Bart could never catch them. He would thump over and drop himself on the floor to pick up his leather bag. Then he'd pull himself upright again, making horrible noises.

Everybody said if he ever caught one of those kids, he'd pull them apart like wet Kleenex.

Shawn hit the front steps running, spotted Rufus across the street and waved.

"What's up, home?" Rufus greeted him.

"You know."

"Yeah, you still fussin' about them shoes, wearin' 'em to school tomorrow?"

"Yeah."

"You got to do it, homeboy. The ladies ain't goin' to see what you worked so hard for they be sittin' in your house, right?"

"Right."

They exchanged a high five, Shawn drawing strength from his friend.

A young man of about nineteen turned the corner, wearing a multicolored leather 8–Ball jacket, black leather sneakers on his feet displaying the distinctive red ball for Reebok Pumps. He hard–eyed the two friends, then dismissed them with a sneer, moving away in a shambling, practiced mugger's gait,

"That mope, he think he bad, doin' the strut like that?" Shawn said.

"Brother, he be bad. That is Marcus Brown, man. You see that jackets Cost you a thousand damn dollars, you buy it in a store."

"So what'd he do, rip it off someone?"

"You don't know 'bout that jacket? That jacket famous, man. Marcus, he roll up on this boy from the Jefferson Houses, throw down on him, point the piece in his face. Marcus, he don't go nowhere without his nine. Marcus say, give up the jacket. This boy, he don't play that…worked his butt off for that jacket, he ain't givin' it up. Marcus, he just squeezes one off. Right in the boy's chest. lees him right in front of everybody. You look at that jacket close, you see a hole right over the heart. Bullet hole, man. Marcus, he one cold dude. Got everybody's respect."

"He don't have mine," Shawn said, his voice laced with bitterness. Marcus wouldn't worry about wearing his fresh sneakers on the street.

That night, Shawn couldn't sleep. He got up and went into the kitchen for a glass of water. Granny was there, cooking something in a big black cast iron pot she brought with her from down home.

"What troublin' you, son?"

It took a long time, but Shawn finally told her about the sneakers. Granny sat at the kitchen table, watching the love of her life struggle with more weight than he could carry.

"What do I do, Granny?"

The old woman looked around the kitchen, brought her eyes back to rest on Shawn. "Go get them shoes for me."

Shawn brought the shoebox into the kitchen. Slowly took out his prizes, laid them on the table like an offering on an altar. Granny held one in each hand, eyes closed. Words came out of her, but her mouth never moved. Then her eyes snapped open, but they looked someplace else. Some other place. Shawn didn't move. Finally, Granny focused on her child.

"Shawn, here is what be. What be the truth. The spirits can't protect things, you understand? Ain't nothing they can do, keep those special shoes on your feet. But I got a spell…an old, old spell that I never used in all my life. What it can do is make those shoes do good, you see?"

"No, Gran."

"I can't swear you keep the shoes on your feet, but, with this spell, whoever wear the shoes got to do the right thing, or…"

"So if somebody take them…?"

"Somebody take them, he have to walk right the rest of his days. Like when you run off from a chain gang…no point in running off to live bad. They just catch you for whatever bad you doin' and back you go, understand? There's crimes that have to change a man. If the man don't change, he got to answer."