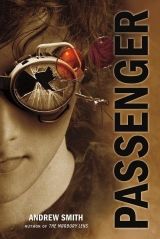

Текст книги "Passenger"

Автор книги: Andrew Smith

Жанры:

Технофэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

fourteen

I dreamed of floating in the sky, being chased by demons.

Jack is putting on a big show.

I had no idea how they could tell it was morning. Being inside the box was like being trapped in a black hole.

I woke when the wooden post Ben used to bolt shut the hatch clattered down against the floor next to my bed.

He pushed the door open with the point of his spear, and I watched with groggy eyes while he and Griffin climbed out of the hole, black shadow puppets against the monochrome Marbury gray that came seeping in from the hallway above.

I followed them. I guess every morning went just about the same for Ben and Griffin. They half ran for the garage, to the side door, and then outside the house to pee in a spot where there used to be oleanders and a lawn. Now there were just broken things, dead things.

They were still angry about what was said the night before, I could tell. Everyone was.

None of us really blamed anyone for our situation, but that didn’t make us any less pissed off about the truths we aired over the kids’ broken-down dinner table. We all knew it would take awhile before we could talk to one another in a normal way.

That’s just how things were.

Ben didn’t look at me. He didn’t need to. He knew I was right behind him while he pissed out onto the ashes, splattering noisily onto an open paint can lying sideways on top of the white dial face of an Edison meter.

“You want to see that dead kid?”

I looked at the pool. There were harvesters, making their little mad tracks over the edge of the coping, out into the ashes, back into the pool, the clicking, the buzzing, eating.

Breakfast time.

“Do you want me to go look at him, Ben?”

Ben turned around and buttoned his pants. “Not really. I was just asking.”

But Griffin walked over to the pool’s edge and reported back, “Not too much left of him anymore.”

And that was all we said, the whole long morning.

* * *

We drank the last of my stolen water and ate some orange sections and beans for breakfast. I opened the cans with my knife. I think the boys knew what I was going to ask them, but I wasn’t about to be the one to initiate the talking. If they wanted to be quiet, it was okay with me.

Finally, I went out to the garage and shook out my socks and T-shirt and put them on. The boys followed, watching me.

I sat down on the stained concrete floor and slipped on my ragged boots.

“Are you going to leave?” Griffin asked.

“You can have everything that’s left of the food and stuff. Sorry I didn’t bring more water.”

Griffin nudged Ben, like he wanted the older boy to say something. “Where are you going?”

“I told you. I’m going to find Conner. He told me where I can get a horse to ride.” I tied my boots and cussed when one of the rawhide laces broke. It had already been knotted together in two other places. This was number three. I stood. “I can’t stay here. I have to find him.”

Griffin said, “You didn’t even ask us to come.”

“If I ask you to come, and things go wrong, then what are we going to say to each other? I told you both I’m sorry.”

Ben cleared his throat. “I’m sorry, too, Jack. None of this is on you.”

“It’s all on me, Ben.”

“I promise not to say anything,” Griffin said. “I promise not to ever say I want to go home again. Please just let us come with you, Jack.”

“It’s not up to me.”

And Ben said, “Come on. Let’s get that shit packed up and go.”

* * *

There once was a supermarket between the park and Cracktown. The kids in another Glenbrook saw it as a kind of border checkpoint where sweaty punks who looked homeless would sit and smoke cheap generic-brand cigarettes along the concrete wheelstops that marked off slotted parking spaces.

During wars, supermarkets are the first territories conquered.

I could imagine what it was like: survivors, at first in large numbers, gathering around the oasis of the store, competing with one another, fattening themselves up, being hunted, and then the water hole turning to dust.

This was real.

We walked, Ben carrying his spear, Griffin, who wore his shirt tied up on his head like we were crossing the Sahara, and me, with one of the kids’ school backpacks that held a few salvaged belongings from their home and the last of our food.

I think just the act of getting out of their house, out of the box, made us all feel a little better, like we had some purpose, something to do rather than just wait.

Maybe we weren’t mad at one another anymore.

But walking past the husk of that old supermarket was scary. The front wall had been entirely destroyed, and most of the ceiling hung down on wires and aluminum framing, uneven and jagged like some abandoned mine. It looked like something where monsters would live, in horror films or nightmares.

Or here.

The entire floor was covered in broken glass and other discarded containers. There were bones scattered everywhere—skulls, pelvises—so many of them you couldn’t tell the difference between the junk that used to be for sale and the junk that used to be a person.

I couldn’t help it. I imagined what it would be like to round up every kid, teacher, custodian, and security guard at our school and bring them to the market and kill them all. That’s what it looked like.

All along the roof’s edge, skulls had been lined up like beads on a string. Every one of them was jawless, dried; some were pale yellow, and others were an amber so rich in tone they almost looked like withered oranges. I saw the heads of children and adults, indiscriminately integrated—all fair and equal access on the roof’s edge. Some had hair on them, but most had been picked clean.

In the darkest depth of the building, a glint of red flame flickered and then dropped behind a pile of rubble the size of a bulldozer.

I stopped and watched, held up my hand so the boys wouldn’t move.

“What do you see?” Ben whispered.

I kept my eyes pinned on the interior of the market. “One of them. He’s back there.”

Ben and Griffin crouched slightly and strained to catch a glimpse of what I’d seen.

Griffin nudged my shoulder. “Where is he?”

I pointed. “Over that way. Against the back wall, I think.”

“Do you think there’s more?” Ben asked.

Hunters never came out alone. He knew that.

I sniffed. Sometimes you could smell them. They smelled like old piss.

“There has to be more.”

“We could maybe take two of them,” Ben said. “Any more than that, we should get the fuck out of here now, Jack.”

And go where? I had to think, calculate the distances to our options. The ag school was maybe two hours’ hike. I hadn’t planned on running into any Hunters out here during the day, but now an unexpected variable had been added to my math.

I sighed.

The firehouse was about fifteen minutes from here. At a dead run, we might make it in five or six. And what if Quinn wasn’t there? What if he wouldn’t let us in?

I pulled out my knife, held it low, next to my thigh. “If we wait here a couple more minutes, and they don’t show themselves, then we know they think they can’t take us. Look at us, we’re just kids.”

Odds.

Griffin moved up between me and Ben. “Do you think he saw us?”

“He knows we’re here,” I said.

Then Ben tapped my arm with the back of his fingers. “Holy shit, Jack.”

He was facing toward the west end of the building, and until he’d said anything, I didn’t even notice that there were ten or more of the things who’d come around in a line, watching us, drooling, licking their teeth.

This was a hunting party, out in the day, which meant they were winning; confidently taking over this other Glenbrook. They were all males, looking for food, for something to bring back to their mates, their offspring. Meat.

More of them started coming out, climbing over the hills of trash inside the supermarket, emerging one by one.

With nothing but a skinning knife and a steel rod, we had no chance against numbers like this.

But they were taking their time. They were going to enjoy doing whatever they wanted to do to us.

In the center of their ranks, the largest male stood at the point of their phalanx. He wore human scalps, molded into a codpiece that covered his nuts. One of the scalps trailed long white hair halfway to his knees, the other, black. The hair had been twisted together, not braided, but clotted with some unimaginable concoction of paste. He was covered in thick purple splotches, and his skin glistened like he’d just pissed on himself. Tusk horns curled around his jaw from the back of his skull, and completely hairless as he was, he looked like some kind of salamander. He was missing his fingers; both hands were twisted into long, hooking claws with talons that looked like they’d been carved from obsidian. In one of them, he held the stump of a club that had been spiked with glass and fragments of bone. Even at my distance, I could see a strand of saliva dripping from his chin, leaking onto the necklace of little pink fleshy souvenirs he wore. Jay Pittman in reverse. And, like all of them, he had one black eye, one white.

The other Hunters in his party stood in the open, uncovered, completely naked. Their scalp-taking had only just started, but some of the others had adorned themselves with decorations: strands of long-dead cell phones, teeth, dried tongues; one of them even had the entire head of a dog hanging in front of his belly, strung through its ear canals on a rope that was likely made from braided intestine. Another wore a pair of women’s glasses on a pearl strand around his neck. It looked like something you’d see on a matronly librarian. And every one of them carried a weapon of some kind. The flankers at either end of the line held bows, pulled tight, arrows angled inward at the three of us.

There was no perceivable way out.

We were dead.

But they all stood still, waiting for the slobbering Hunter at the center of the line to direct their game.

Time for fun.

I didn’t move. “Griff, listen to me. Unzip the backpack and take the sock out. The sock with the glasses in it.”

“Don’t leave us, Jack!” Griffin was beginning to panic.

I whispered, “I’m not. Just do what I said.”

The Hunters began creeping toward us, completely unconcerned, certain they were going to have exactly what they wanted. I could hear their mouths working, licking, teeth clattering, nearly choking on the flowing saliva of their anticipation.

I felt Griffin opening the pack.

Ben faltered. He was breathing so hard. He jerked around, turned as if to run.

There was no way we’d outrun them. Trying to run would only make them more excited, horny for us. It was pointless.

I grabbed Ben’s shirt and held him steady. “Don’t.”

Ben couldn’t catch his breath to answer. I thought he was going to pass out.

I squeezed the knife in one hand, then I let go of Ben and put my other hand out for Griffin. “Give me the lens.”

There was always a peculiar weight to the Marbury lens. It wasn’t from gravity; it came from something else altogether. And even though the lens was dead to me now, I could still feel the heaviness it contained when Griffin placed the fragment onto my open palm. And as soon as he did, the boy whispered a hushed “What the fuck, Jack?”

Then the world went red, as if I were looking at it through a glass of wine.

Ben turned and stared at me. His mouth hung open, and when I lifted my hand in front of us, everything began to change, dissolve before our eyes; like being back in that garage on the day I smashed the lens.

Something pulled me up, by my hand, like it was on a string.

Ben and Griffin, the Hunters, the wreckage in front of us, the endless scorched nothingness of Marbury, all of it began smearing together in the red light, melting, liquefying.

I could hear Ben repeating Holy shit! Holy shit! but it was almost as though my eyes had been pulled out from my head and were floating in the stagnant air above, because I clearly remember that I was looking down on the three of us, seeing us as we stood there and watched the Hunters moving in, surrounding their kill.

From above I watched, and everything became so intensely bright and clear—Marbury, but in color, like a cartoon rendering of hell.

Then came the shrieking; the pained, hissing cries of the Hunters. Some of them began circling; just standing in place, but circling around as if they were completely surrounded by the worst things they could imagine. The one with the dog’s head hanging on his chest began clubbing the Hunter next to him, wildly smashing his skull, pounding and pounding even after the Hunter was clearly dead, until there was nothing recognizable left from the shoulders up.

And the archers on the flanks turned toward their own, releasing a volley of arrows. More screams and wails. Reloading, and more arrows. I could hear the sound made by their whisking fletches, by the impact of each arrowhead popping through strained flesh like an overripe plum.

In the center of the mass, the big one, their leader, began wildly clawing into his own eyes. It looked like he was suddenly growing hair, and I noticed that all the standing Hunters started tearing at one another with their hooked hands. The dark hairs got thicker, squirming, wriggling, and I could see clearly how it was the worms, the suckers, bursting out from their skulls, erupting from the taut, naked hides, from every surface of their splotched skins, until each Hunter that was still alive became a writhing and frantic clot of black maggots.

The sound was sickening—like thousands of toothless babies suckling hungrily—until every one of the Hunters fell in wriggling heaps of gore.

I closed my hand.

Everything went dark.

I don’t remember hitting the ground.

fifteen

“Jack?”

I am looking up.

The sky is infected, gray, rotting. It’s always like that.

“Come on, bud.”

Ben is floating in the air over me, his face so close to mine I can feel the tickling exhalations from his nostrils. His hand is on the side of my head, rubbing my hair, patting me.

“Are you here? Do you know where we are?”

I say, “Fuck.”

“You stopped breathing.” Ben tries to smile. He looks pale, scared.

“Was I dead or something?”

“I don’t know.”

My voice is a distant croak. “Did you see that shit, Ben?”

“Yeah.”

It’s like a camera, panning back. Now I see Griffin kneeling there beside my head. His face is wet. Griffin never cries about anything. He’s been crying now.

I look at him. “Don’t say you want to go home, Griff, or I’ll get up right now and fuck you up.”

I know the kid wants to go home.

He wipes a trail of snot along the back of his wrist. “What the fuck was that, Jack?”

I cough. “Fuck.”

And Griffin says, “Well, unfuck it, Jack.”

* * *

I honestly can’t say what happened to me.

It was pure nothingness.

Ben and Griffin told me that I’d stopped breathing and they both exhausted themselves trying to resuscitate me. They were going to give up. More than an hour had passed between the time when Griffin placed the broken lens into my palm and my eyes opened to look up at Ben, floating in the gray sky above me.

If that was what dying was like, it wasn’t as terrifying as I’d convinced myself it would be.

It was complete.

My entire body felt so rested, like every joint had separated, every fiber in me unraveled entirely.

“Help me up.”

They each grabbed beneath my shoulders and I sat. I drew my knees in and looked across the dirty dust at the gaping grimace of the supermarket façade.

There was blood everywhere. Strands of innards snaked through the dust in the gobs of mucus excreted by the worms.

Ben took a long, deep breath. He swallowed. “We thought you were dead.”

“I didn’t think anything.” I braced my hands on the ground beside my hips. “Let me see if I can stand up.”

It was real, all of it.

I guessed there were maybe thirty Hunters who’d come after us. They were scattered everywhere between where I stood and the front of the market. And the sound of the eating harvesters that had already swarmed over the corpses, as they picked between the leathery and dying worms, tearing, pulling, grinding, was like the crackling of a bonfire.

The smell was horrendous.

I turned away, looked at the sky. It was already getting late.

Griffin wore the book bag. One look at him was enough to say everything. The shit we saw scared them. Bad.

“The lens?” I said.

Griffin patted the pack’s shoulder strap with one hand. “It’s in here.”

“Okay.”

And when I started walking again, past the supermarket, my knees buckled and I nearly fell face forward. But the boys must have known I wasn’t all there, so they caught me before I went down.

“Take it easy, Jack,” Ben said.

“We need to get out of here.”

I’d never seen Griffin look so scared and lost. His face was streaked with the ashy Marbury filth that muddied his tears. He said, “Maybe we should go back to the box. So you can rest. We can try again in the morning.”

“We’re just going to keep getting trapped there, Griff.”

Ben sighed, frustrated. “What do we do? Tell us what to do.”

“We’re going to get horses tomorrow. The ag school might be too far for me right now. I know where we can go.”

“Where?”

“The fire station.”

* * *

It’s the water that kills you in Marbury.

Without it, you give up, go crazy, make stupid choices, become a meal.

And the rain is poison; it brings the worms.

Fuck this place.

The boys knew their way. I tried pushing them to get to the station as quickly as possible. I didn’t want to have to deal with any more Hunters. I knew that if Jack stopped breathing again today nobody was going to be able to spit and slobber enough life down his fucking throat to bring him back.

Welcome home, Jack.

I fell down twice, tripping over broken cinder blocks. The knees of my jeans were torn through, dotted with stinging blood.

And each time I’d fallen, the boys would rush over to me, frightened, to help me back up. They knew I was in bad shape, too.

We never said a word.

We were so thirsty.

I don’t know how we kept going; why we didn’t simply sit down, give up, and rest.

When we passed the little schoolyard, I looked over at the playground, the rocket-ship jungle gym. There were more bodies there. Three little Odds. Fresh, stripped, gutted, headless, hanging upside down by their feet.

I saw Griffin looking at the display. Maybe he’d known one of them, played flag football against him in PE at another school in another Glenbrook where things like grass and drinking fountains were so commonplace they became invisible.

It was almost impossible to believe that there were any kids left alive here at all.

They came out searching for water.

“Don’t look at that, Griff. We’re almost there.”

Then I fell down again, got a mouthful of ash. It started to choke me, and I would have thrown up, but my stomach was like hardened concrete.

I stayed there on all fours, trying to spit my mouth clean, but nothing would come. My mouth felt like tree bark in a desert.

“Here.” Griffin sat down, Indian-style, in the dust beside me. He swung the pack around onto his lap and opened it. He pulled out a can of sliced beets.

Who eats those things, anyway? No wonder Quinn Cahill found them.

“Let me have your knife,” Griffin said. “We can drink the water out of this.”

I didn’t care anymore.

I handed Griffin my knife and watched while he pried two triangular holes into the top of the can. Then he handed it to me and I drank. I felt the ash in my mouth clot like a scab, but I swallowed anyway. When I spit down onto the ground, it looked like I was spitting out my own guts.

“Fuck.” I wiped my mouth with the back of my arm and passed the can to Griffin.

He grimaced when he swallowed. “This tastes like piss.”

Ben finished the liquid from the can of beets. “You want to eat this shit?”

I shook my head.

Ben dropped the can onto the street and we kept walking.

The rain came again.

When we got to Quinn’s firehouse, we were soaked, our pants plastered against our legs. We had taken off our shirts and wore them on our heads.

The water rose slowly here; the firehouse sat on a hill, so we were safe from the worms for the time being. It was the ash everywhere on the ground that prevented the water from soaking into anything, and as soon as the rain would stop, the Marbury heat sucked the temporary seas dry, back up into the ulcerous gray sky that delivered them.

Griffin kept watching his feet while he cupped one hand under his balls.

Ben said, “If he doesn’t open the door, we’re going to have to bust in.”

I saw Quinn’s canoe sitting on the side of the station beside a post office mailbox with its gut-door pried off. There was what looked like an arm bone inside. Nothing else.

“He’s got the place booby-trapped. It’s dangerous. We can figure something out.” I pounded my fist against the door. “Quinn! Cahill! It’s me, Jack!”

We waited.

It poured.

Ben kicked the door. It made a sound like explosions inside the cavernous firehouse. If Quinn was inside, he knew we were there.

Griffin pressed up against me when the first boom of thunder erupted over our heads. Here in Marbury, it came so loud, you could feel thunderclaps echoing in the center of your guts.

“We need to get out of the rain,” Griffin said.

The water inched its way toward us, higher up the slope of the hill. I could see the worms slithering at its edge, like they could smell us standing there. And for a moment, I couldn’t help but picture the image of all those millions of black worms sprouting like weeds through the skin of the anguished Hunters.

I pounded a second time. “Quinn Cahill! Please!”

Another explosion of thunder. I could feel both of them—Griffin and Ben—jump at the sound.

And then, from above: “Billy? Is that you?”

The three of us looked up at the same time to see a scrawny redhead kid smiling down at us from his rooftop deck.

Quinn Cahill.

“You been a bad friend, Billy. You took from me. That just ain’t right. You should have did what I told you.”

Why was it that I always found myself wanting to punch him? At least the adrenaline rush of Quinn Cahill’s constant pissing me off had a weird rejuvenating effect on my sorry state.

And Ben whispered, “‘Billy’? Who the fuck is Billy?”

“He just fucks with people,” I said. “Constantly. He’s a little fucking prick.”

Then I raised my voice so he would hear me. “I apologize for that, Quinn. I was afraid of the Rangers, so I ran. Please help us. We’re kind of in a jam.”

Quinn’s head disappeared and then popped back over the edge of the building. He swung his arms into sight and pointed the bright red speargun directly at us. “What do I want with some useless Odds, Billy? You can all get on back to wherever you came from. Well, them two can. I’ll allow you to stay, Billy. Just you. I like you, Billy. But them other two need to get.”

I looked down, whispered, “He’s fucking insane.”

Griffin pressed his body flat against the door. Quinn was just posturing. There was no way he could shoot one of us from where he stood. And I didn’t think he was honestly crazy enough to actually kill another kid—an Odd—anyway, but I wasn’t willing to test my theory about that either.

“I can’t leave them,” I said. “I’ve known them forever.”

“Okay. Well, good-bye then, Odd.”

And Quinn Cahill disappeared behind the wall of cinderblock above us.

I kicked the door. “Fucking sonofabitch.”

“Is he joking?” Ben seemed unable to grasp Quinn’s cut-and-dry outlook on things.

Griffin stomped his foot down. I looked. With the heel of his shoe, he’d cut one of the black worms in half. “We need to get out of here.”

I raised my hand to pound again, but I gave up. It was no use. To Quinn, everything was about winning, and knowing that should have made me wonder why he was always so eager and willing to keep me around. What was the gain?

“I fucking hate that guy.”

What could we do? The water was rising fast. We’d all be struggling against the worms in a minute. And that was a fight we’d end up losing. Our only chance was taking Quinn’s canoe—stealing from him again.

I sighed. “Fuck.” Then I bent over and began untying my bootlaces. Someone was going to have to wade out after the canoe, and I couldn’t expect Ben or Griffin to do it; not after all the shit I’d already put them through.

By the time I’d gotten my socks pulled off and managed to roll my pantlegs up over my calves, I already had one of those black things worming across the top of my foot, slithering up from between my toes. I pinched it, flicked it away, and daubed at the bead of watery blood left behind by its circular bite.

“Anyone else want to come with me?”

Ben and Griffin just stared at me like I was a lunatic. “This is going to be fucking fun.”

I took a deep breath, and was just about to step out into the water when the firehouse door opened and the redhead stuck his face out. And he was still pointing that speargun of his, directly at the center of my back.

“I’ll shoot anyone who touches my boat, Billy. That’s just how it’s going to be.”

I spun around, my hand clenched in a fist, ready to unload on him. “What the fuck do you want me to do, Quinn? You want to fucking stand there and watch while we get eaten alive?”

Griffin and Ben moved away from me, as near as they could get to the edge of the water. I couldn’t blame them for stepping back. It was a rock and a hard place, and I’d never expect them to take a shot that I deserved. After all, it was my idea to come to the fucker’s house in the first place.

Everything was my idea.

Quinn waited in the doorway and stared at me for a while. He had a hurt look on his face, like a kid who nobody wanted to play with; who got picked last for a team.

“Okay, Billy. No need using foul words. I was just seeing how you’d stand. Who you’d stick up for in the game. You know … yourself or your partners there. You are partners, right?”

I wanted to howl, to kick him in the teeth.

“Yes. We’re partners, Quinn. That’s how it is.”

Then Quinn pointed the spear tip down at my foot. “Uh. You want to watch that, Odd.”

Two more of the worms were on my right ankle, coming up. A third was already disappearing inside the left leg of my pants. I pulled it out through the hole in my knee, ripped it apart between my fingers. Then the other two. Both of my legs and hands were covered in blood.

I held my palms out, open to Quinn.

“What the fuck, Quinn? Come on.”

Quinn lowered the speargun and swung his door open. He stood back to let us inside. Even though he was giving in to me, Quinn Cahill made it clear that he was the winner.

“I was just measuring you up, Billy. You’re okay. You two partners got a good friend there. A real good friend!”

And Quinn patted Ben and Griffin warmly on their wet backs as they went through the door to his firehouse. I bent down and picked up my socks and boots.

Quinn said, “Now don’t be tracking in any of them suckers with you, Billy! Ha-ha-ha…”

But as I passed him in the doorway, he put his arm around my shoulders and whispered, “It would be better if it was just you and me, Odd. You’ll see. We don’t need them two, Billy. Okay?”

As he led me up the stairway to his living floor, Quinn kept squeezing me tight, like how you’d hold on to someone you’d been missing for years, patting me until I finally broke down and said what he wanted to hear.

“Thank you, Quinn. You’re a good friend.”

And I knew then that if I ever had to kill Quinn Cahill to protect the boys, or to make certain we’d be able to get home again, I’d give it about as much thought as plucking one of those fucking worms off my nuts.

Quinn slapped my shoulder.

“I told you we’d be friends, Billy. Told you.”

* * *

First he had to give my “partners” a grand tour of his palace.

Quinn pointed out the two beds, explained how the one with no sheets was “Billy’s,” and told Ben and Griffin his story about the ungrateful Odd who made a rope with sheets and ran away when Anamore Fent’s team came by, hunting for him.

“But you two Odds can sleep down on the floor. Don’t worry, I got plenty more bedding, which I intend is not going to be put to use for anything other than you two fellas sleeping on.”

Griffin glanced at me and shrugged, and I tried to give him a look that said to just go along with the idiot.

“And what’s your names, anyhow?” Quinn said. “If you got any names, that is.”

Some Odds didn’t have names, or didn’t need to remember them.

“Ben.”

And before Griffin could say a word, Quinn snapped, “Ben’s a easy name to remember. Okay. Good enough. Ben and not-Ben.”

He smiled his toothy, freckled, redhead smile at Griffin, who was now going to have to endure Quinn’s permanently calling him not-Ben.

“My name is Griffin Goodrich.”

“That’s fine, not-Ben. You just hang on to that memory. You never know when you might have to tell it to someone who cares.”

Now, I was sure, at least two of us wanted to punch him.

Then, naturally, Quinn showed the boys where to pee, and how he had his big urinal trough hooked up to a collector so he could make drinking water from piss.

“Heh-heh … we’re going to have plenty of new drinking water, ain’t we?”

And Quinn rapped his knuckles against the lower lip of his steel urinal, so it made a ringing sound like a church bell.

“Turning our pee into water. You’re just like Jesus in reverse,” Griffin said.

Quinn’s smile vanished. His face went blank. “Who?”

“Jesus,” Griffin said.

“I don’t know what that is. No one never showed me nothing about making water out of my pee. I figured it out on my own. From intellectual reasoning, not-Ben.”

Griffin said, “Oh. Okay, Quinn.”

* * *

I think it rained harder that night than any time I could remember here.

I slipped into the shorts Quinn had given me; everything else I owned was wet or falling apart. Quinn didn’t offer any dry clothes to the “partner boys,” but he did provide plenty to eat and lots of drinking water.

Ben and Griffin insisted that I drink first, and they watched my face to see if I’d show any sign that it tasted like anything other than what Quinn promised it to be. Griffin must have drank more than a gallon on his own. He said he was trying to make himself pee, because he wanted to see how Quinn’s still worked.

Eventually, everything had to be turned off in the night with the exception of one dim oil lamp, so we lay there, all of us just staring up at the ceiling, listening to the incessant roar of the storm against the concrete of the firehouse.