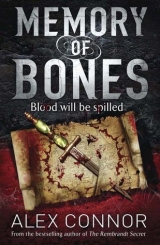

Текст книги "Memory of Bones"

Автор книги: Alex Connor

Жанры:

Ужасы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

45

Richmond

Walking up the driveway to a secluded eighteenth-century house outside London, Ben ducked under some overgrown hydrangea bushes as he reached the front door. Wisteria, grown reckless, knotted about the windows and the porch, and a rose – long in the tooth – raked its thorny teeth against the brickwork.

Finding the bell, Ben rang it several times before footsteps approached the door, a young woman opening it and smiling.

‘Can I help you?’

‘I’ve come to see Mrs Asturias. My name’s Ben Golding. She’s expecting me.’

Elizabeth Asturias was sitting in the breakfast room, nursing a copy of the Telegraph and a cup of tea. As Ben walked in, she took off her reading glasses and jerked her head towards the dining chair next to her.

‘Nice obituary for Francis in the Telegraph,’ she said, tapping the paper with her index finger. ‘Bastards didn’t have the same kind words for him in life.’

The comment, delivered in razor-sharp English, came as a shock. Over the years Francis had mentioned his wife in passing, but always with dry humour, suggesting that the classy Elizabeth had had little time for him and less affection. But the ageing woman Ben was now looking at had the telltale puffy eyes of grieving and an unexpectedly short temper.

‘I told him to retire – would have liked him home.’ She stopped, shouting at the young cleaner. ‘Careful! I can hear you clattering those dishes about. They chip, you know.’ She glanced back at Ben. ‘He liked you.’

‘I liked him.’

‘Hmm,’ she said simply, tossing the paper to one side. It landed on the floor like a shot bird. ‘They killed my poor lad. Francis … Of all people. It’s so … unnecessary.’ Her eyes filled and she wiped them briskly with the back of her hand. ‘Killed him. Who would do that? Why would anyone do that?’

‘I don’t know—’

‘Oh, don’t lie to me!’ she snapped fiercely. ‘I was married to him. I knew what was going on. Francis used to tell me everything. Of course I pretended that it bored me, but he knew I loved the gossip.’ She sighed, staring at her fingernails and wincing as the cleaner made another noise. ‘Go for the post, dear!’ she snapped. ‘Oh, and get some bread from the shop while you’re at it.’

They waited for the young woman to leave, Elizabeth watching her pass the window and go down the drive before turning back to Ben.

‘Now we can talk properly. Francis told me about that bloody skull of yours. Or should I say, your brother’s?’ She raised one eyebrow. ‘He’s dead too, isn’t he?’

Her directness caught Ben off guard. ‘Yes, he is.’

‘Killed, I believe?’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Francis did! Don’t be bloody coy,’ she said shortly. ‘I’ve told you, he told me everything. He said you were insisting that your brother was murdered.’

Ben paused, surprised by how much she knew.

‘I came to pay my respects—’

‘Bullshit! You came for something else,’ she said perceptively. ‘I know you were in Madrid and couldn’t make the funeral, but you sent me a letter and a wreath – you had no need to come and pay your respects in person. Unless you wanted to ask me something.’

‘You’re smart.’

‘I know,’ she said bluntly. ‘Retired university lecturer in Classics. I was a psychotherapist too. Francis won’t have told you that; he hates – hated – shrinks.’ She glanced over to the window and the view of the drive. ‘I’m sorry I never met your brother – he sounded interesting.’

‘He was.’

‘Why do we always lose the good ones, hey?’ she queried, tapping the teapot with the arm of her glasses. ‘You want a cup?’

‘No.’

‘I don’t blame you. The cleaner makes bloody awful tea.’

Smiling, he thought for a moment then glanced back at her.

‘You’re right, I did come to ask you something. Francis reconstructed a skull for me—’

‘The Goya skull?’

‘Yes, the Goya skull,’ Ben replied, ‘but you don’t know that.’

‘I’ve just told you.’

‘But now you have to forget that you know about it, Mrs Asturias. It’s not safe for you to know about it.’ He paused, trying not to alarm her. ‘Francis rang me just before he was killed …’

‘And?’

‘He told me that someone had stolen the skull.’

She was genuinely shaken.

‘He didn’t tell me. Poor sod didn’t have time, I suppose.’ Her bravado was her way of coping, keeping back the grief. ‘You know who took it?’

‘No,’ Ben admitted. ‘But there’s more. The skull that was stolen wasn’t the real one. Francis had swapped them. Whoever has the skull now, has a fake.’

Caught off guard, she laughed, shaking her head.

‘How like him! Francis loved to make everything complicated. Couldn’t let anything be simple …’ Pausing, she caught Ben’s eye, her intelligence obvious. ‘So where’s Goya’s skull?’

‘I don’t know. Francis was going to tell me, but he didn’t have a chance. That’s why I’m here – to ask you if you know.’

‘No, I don’t.’ She was genuinely regretful. ‘If I did, I’d tell you.’

He had expected as much, but the disappointment still stung. ‘Did Francis have a workshop here? Or a study?’

Rising to her feet, Elizabeth moved over to the door. She was unexpectedly tall. Beckoning impatiently for Ben to follow her they moved through the hall and down a narrow passageway into the kitchen, then walked across a courtyard into an outbuilding. The property was decrepit and neglected, but obviously of considerable value. And Francis’s retreat was just as impressive.

‘He used to sulk in here,’ Elizabeth said fondly, holding back the door. ‘We had a wonderful sex life, you know. Even up until his death. Wonderful lover.’ She glanced over at Ben. ‘You’re shocked, of course. The ageing population isn’t supposed to have desires, is it?’

‘Why not?’

She winked, amused. ‘Good answer!’ Sweeping her arm across the room, she went on. ‘Help yourself. Have a rummage – I don’t mind. This is all of it. Francis loved machinery, computers, all kinds of technology – you name it. The dotty professor act was just that – an act. He could tackle anything.’

Walking around, Ben opened cupboards and searched them, bending down to look at the neatly stacked shelves. They were filled with paint tins, machinery, and hundreds of tools of all shapes and sizes. But no hidden boxes, no crumpled bags, no concealed skull.

Still searching, he asked, ‘Did he spend a lot of time surfing the net?’

‘The only net Francis surfed was the one he used when he went fishing.’ She pointed to his fishing tackle. ‘Have a look in the basket – it might be there.’

Ben did as he was told.

‘No, nothing.’ He glanced back at her. ‘Where would he hide something? You knew him, you knew how he thought. What would Francis use as a hiding place?’

‘He used to hide his cigars behind the bath panel, but I found them and he never did it again.’ She paused, thinking. ‘If he brought the skull home, he would have hidden it here for safety. Kept it away from me and the house. He knew what a bloody nosy old bat I am … But we don’t know for certain if he brought it home.’

‘No, we don’t.’ Hurriedly, Ben continued his search, then glanced over at the row of blank computers.

‘Did Francis use the internet for work?’

‘Oh no! He just liked to fix computers. Take them apart and then put them back together again. Or buy old ones’ – she gestured to one of the first Amstrad machines – ‘and repair them. I suppose it wasn’t so different from what he did at the hospital, putting people’s faces back together again.’

Ben pointed to a door. ‘May I go in here?’

‘If you want to have a pee, go ahead.’

Amused, Ben walked into the lavatory and checked the cistern. Empty.

‘Did Francis talk about all his reconstructions?’

‘What?’

He moved back into the main room so that she could hear him. ‘Did he talk about the reconstructions?’

‘Only the interesting ones.’

‘What about Diego Martinez?’

‘The man who was chopped up and left all over London?’ Elizabeth nodded. ‘He liked that case, although he did say that when he’d reconstructed the head he was disappointed. Thought the man looked dull. He said that his death was probably the most dramatic thing that had ever happened to him. Francis felt sad about that one.’ Her expression veered between affection for his memory and the remembrance of his loss. ‘He had such respect for people. Such fondness …’

Still walking around, Ben opened the worktable drawers. ‘May I?’

‘Help yourself.’

‘What did he say about the Goya skull?’

‘He was proud to have reconstructed that head,’ she said simply. ‘I’ve always loved Goya’s work, but Francis wasn’t interested in art. Having said that, he was touched by what he did. I even found him looking at some of Goya’s work afterwards. That was a bloody surprise.’

He glanced over at her. ‘The skull’s not here, is it?’

‘I think you’d have found it if it was,’ Elizabeth replied, sighing. ‘D’you want to search the house?’

‘Can I?’

She shrugged.

‘I don’t mind, Mr Golding. The skull means nothing to me. And if it helps you to find out who killed your brother and my husband, I’ll give you all the help you need.’ She held his gaze. ‘Yes, I’ve worked it out. Diego Martinez, Francis – they’re connected by the skull, aren’t they, Mr Golding? I think they must be, because otherwise you would never have warned me to forget everything I knew about it.’ She turned to the door, flicking off the light but inadvertently turning on another switch.

Surprising both of them, the computer next to Ben came on.

‘Is this one fixed?’

‘The only one that is,’ Elizabeth replied. ‘The rest were work in progress.’

Connecting up to the internet, Ben ran down the Received and Sent emails. Elizabeth had been right: her late husband hadn’t spent much time using the computer, and less sending messages. There was nothing of interest, mostly spam. Then, for some reason Ben could never explain, he checked the Delete file.

And there, in among emails from seed catalogues and Amazon was the address Gortho@3000.com.

46

Madrid

Prosperous in a dark silk suit, Bartolomé Ortega walked towards the graveside. The heatwave had not returned; the weather had cooled its heels and the late sun was now limp, leaden with cloud. Outside the city, across the river, the old cemetery gates creaked solemnly in the dry, brisk breeze. Occasionally they shuddered against their rusty hinges, the lichen-coated stone eagles portentously silent on the gateposts above.

Also silent, Bartolomé Ortega glanced ahead. There was a reasonable turnout for Leon Golding’s funeral, and even though the coroner had ruled it a suicide he was pleased to see that the body would be laid in consecrated ground. Punishment after death was for God, not man. But although Bartolomé was feeling generous towards Leon Golding, his anger with his brother had not lessened. Every day he waited for Gabino to come to him with the news of the skull, and every day he stayed away deepened their rift.

Behind his sunglasses, Bartolomé looked around, his gaze fixing on the figure of Ben Golding standing as though immobilised beside his brother’s grave. His presence was as impressive as always, but there was a poignancy, a kind of desperation about the man which caught, and held, Bartolomé Ortega’s attention. Ben Golding’s grief was absolute, his silent guard as eloquent as a thousand pious words.

Slowly, Bartolomé’s gaze moved across the other mourners, nodding to several people he knew. Then he spotted a woman standing slightly to one side, a good-looking redhead who seemed familiar.

‘That’s Leon Golding’s girlfriend. Well, she was …’ he heard someone whisper behind him.

So this was Gina Austin, was it?

Bartolomé studied the woman who had once been Gabino’s mistress, her honed, athletic body evident even under the mourning black. She was trying to be inconspicuous, but her movements were too extravagant for a funeral and he found himself automatically disliking her. There was no doubt she had beauty, but she seemed to be more interested in the living Golding than the dead one.

Solemnly, they all watched Leon Golding’s coffin being lowered into the ground, Bartolomé wondering momentarily why he had lost out on the greatest find in art history. If Gabino had told him about the Goya skull he would have got it away from the historian, would have made certain that an unbalanced man wasn’t left in charge of a priceless artefact. He had admired Leon Golding’s brain – and had always feared that the Englishman would solve the mystery of the Black Paintings before he did – but to be bested by him was unbearable. And it was all Gabino’s fault.

Disappointment left Bartolomé limp. If only he had got the skull away from Golding, taken the object under his own weighty and wealthy wing. He would have offered his services to the Prado immediately, impressing upon them the importance of the find and the equal importance of preserving it, and how he was the best person to undertake the mission. But his brother had kept quiet and Bartolomé had missed his chance. And now where was the skull? London, probably, with Ben Golding, Bartolomé thought bitterly. It could have been his. It should have been his – if his idle brother had secured it for him.

His face expressionless, his eyes narrowed behind his dark glasses, Bartolomé kept watching Ben, thinking of the Golding brothers. Thinking enviously of their bond – a closeness he had never experienced with Gabino. He could see the loss in Ben Golding’s face and thought of the skull again and of the old rumour which had surrounded it. Some had sworn that it was cursed. That anyone who touched it was tainted. The same people spoke of the Black Paintings in hushed tones. There was a meaning to them, they said, but it was fatal to the person who uncovered it.

Such superstition used to amuse Bartolomé, but he was no longer quite so sure that mockery was justified. And, as a cloud shifted over the cemetery, he felt a distinct unease. A hoarse wind blew up, throwing dust about the mourning stone angels and the dilapidated urns. Holding her hand to her face, Gina turned away, but Ben Golding stood motionless as though he hadn’t noticed the turn in the weather, the sun whey-faced behind a darkening cloud.

Glancing at the grave, Bartolomé stared at the coffin of Leon Golding, the varnished wood already spotted with the first bold shots of rain. Soon there would be a downpour, he thought. Water would fill the grave. Over time a little would leach into the coffin, the Spanish earth holding fast to its adopted son.

But it wasn’t Leon he pitied. Instead, Bartolomé looked back at Ben Golding and realised that if there was a curse, it had already found its next victim.

47

‘What do you want?’ Gabino asked, walking past Gina in his office and moving out on to the balcony.

The heat was stifling, the earlier storm having passed, the sound of traffic rising from the street below. He looked down, Gina moving over to him and standing only an inch away, their shoulders almost touching. She was banking on his previous desire for her, hoping it could help to reinstate her into the powerful Ortegas. But Gina was no fool. Gabino had rejected her once and she needed more than the lure of sex to reel him in.

‘I’ve missed you—’

‘Especially since Leon Golding killed himself,’ Gabino replied, bad-tempered with the heat, a sore throat making him irritable.

‘I loved you,’ she said, touching his arm. But the action only annoyed him and he shrugged her off.

‘It’s over. It was over a long time ago. Don’t come back here now you need another meal ticket.’ He leaned towards her, his face pushed close to hers. ‘You had your turn.’

Stung, she kept her temper. This was no time to lose control. Gina knew that her looks were at their height, but within a couple of years they would wane, their rangy athleticism lunging fast to wiriness. If truth be known she had latched on to Leon at a party, hoping that by being with him she might move on to his more illustrious brother. But Ben had never shown the least interest in her, and Gina had found herself in the tiresome position of being the girlfriend of a brilliant, but hysterical, man. Determined to make the most of her situation, she had given herself another year to entrap Leon and had been sure of success – until events had altered everything.

‘Don’t you feel anything for me?’ she asked, still standing beside him, as though she could force some intimacy.

He shrugged. ‘You were a good lay.’

The words punched the air out of her and cemented her plan.

‘I see … So you’re not interested in the Goya skull any more?’

He turned so quickly it was as though he had been spun round. ‘You’ve got it?’

‘What if I have?’

Suddenly he was all attention. The skull – the way back into his brother’s wallet.

‘Gina, you sly one,’ he teased. ‘What are you playing at? I mean, I knew Leon had the skull, but I didn’t imagine that he gave it to you … Or did you take it?’

Pausing, she juggled her words.

‘You want it?’

‘You know I do.’

‘For Bartolomé?’

He shrugged again, but this time Gina laughed.

‘Don’t try and fool me! I heard about the court case. Well, everyone in Madrid’s heard about it. I suppose your luck would run out eventually – everyone’s does.’ She was baiting him, back in control and repaying him fully for insulting her. ‘I imagine that if you could give Bartolomé the one thing he wants above anything else he would do you a favour in return. Perhaps see to it that you don’t go to jail.’ She sat down, crossing her legs, mean-spirited. ‘Your brother could do that, couldn’t he? I mean, he has the money to organise something like that.’

Silent, Gabino watched her as she continued.

‘But the question is, would he? Bartolomé’s really pissed off with you, Gabino. You always tried his patience. I remember when we were together you mocked him so much, and always expected him to take it. But no one takes it forever, do they? You’ve disgraced the Ortega name and he could make you pay for it. I mean, your own father was disinherited, wasn’t he? I suppose Bartolomé could do the same to you.’ She looked round. ‘All this money, power … all your toys – it would be hard to lose all that, Gabino. Not many women would be interested in visiting you in jail if you had nothing.’

His expression was hostile. ‘So what are you offering?’ he asked. ‘You are offering something, aren’t you?’

‘I can get the skull for you.’

‘Really? Who’s got it?’

‘Leon’s brother.’ She was intent, watching Gabino’s face, watching him trying to disguise his interest.

‘Are you sure?’

‘No, not sure,’ she admitted. ‘But Leon didn’t have it with him when he killed himself and it’s not in the house. I know – I’ve searched. So I reckon he must have given it to his brother.’

‘And you think Ben Golding will give it to you?’

‘No,’ she admitted. ‘I think I’ll have to get close to him, find out where it is, and then tell you.’ She paused, letting the implication work on him.

‘You’re such a whore.’

‘And you’re different?’ she countered. ‘You’d sell yourself for money any day, Gabino. You need this skull – really need it. And I’m the only person who can get it for you.’

‘And how much is this going to cost me?’

She moved over to him, her hand resting against his flies, her fingers moving rhythmically.

‘I liked being your woman, Gabino. Liked the lifestyle.’ Her lips moved against his neck, her breath hot. ‘You missed me – you know you did.’

He kissed her eagerly, then drew back, looking into her upturned face. ‘How long will it take you to get the skull?’

‘Not long,’ she said confidently. ‘Ben Golding’s a man, isn’t he?’

48

After his brother’s funeral, Ben returned to the empty farmhouse and walked the rooms like a stranger. His thoughts drifted between Leon and Francis Asturias, wondering why the dead reconstructor had had an email from the same source as Leon. Gortho@3000.com. Had he talked to someone? Had Francis found himself incapable of keeping the skull a secret? Or had the draw of big money proved too much for him?

No, Ben thought, it wouldn’t have been that. Francis had been born into money, had no need to make more. So was it a need for excitement? Or danger? Francis was getting old. Did he crave some spark of a thrill? Did he fancy himself part of a scenario which spoke of the past, a dying painter, and a relic which would be lusted after? Perhaps he didn’t realise at first what it would lead to, and when he did it was too late … Above all, Ben wanted to believe that his old friend had not betrayed him. That it had been folly on the part of Francis, not malice. Not treachery.

Moving into the bedroom Leon had shared with Gina, Ben looked around. One wardrobe was crammed with Leon’s clothes, some arranged in perfect order, others haphazard on hangers. Next to it was another wardrobe. But this was empty and the adjoining bathroom that Gina had used was cleaned out too. All that remained was a deodorant and a lipstick in the medicine cupboard.

Thoughtful, Ben moved over to the bedside cabinet and opened the top drawer, surprised to find Leon’s medication and remembering his brother’s panic.

… Have you got your pills?

They aren’t here!

They must be. Look again.

They’re not bloody here! And Gina’s not here either.

But the pills had been there all along. And the police had said that when they checked the house Gina had been there too. So had Leon been mistaken? Walking out of the bedroom, Ben paused on the corridor outside, looking towards the window at the end of the landing. Long ago Detita had arranged to have bars fitted. She told Leon that it was to stop anyone breaking in, but to Ben she had said it was to stop his brother jumping out.

Breaking in, jumping out … Flicking on the lights to brighten the sombre hallway, Ben moved downstairs. He tried to convince himself that the funeral proved Leon’s death, but his brother was still everywhere – a garden hat on a hook by the back door, a glass with his fingerprints, and the desk chair with a worn cushion which Leon had always tucked into the small of his back. Memories choked the farmhouse, they hovered in the garden and called from the cupboard under the stairs. Every little terror Leon had ever felt crowded into the house; every broken night and hazy day stood in testament to him until Ben could bear it no longer and made for his brother’s study, slamming the door behind him.

He had checked on Abigail earlier. When he phoned the Whitechapel he had been told she was sleeping. Telling the sister not to wake her, Ben passed on a message. Then he asked to speak to Dr North. To his intense relief, Ben was told that the biopsy was benign.

‘… but there’s some muscle degeneration in her cheek, due to scarring from previous surgeries. It will need an operation, Ben. I can do it, if you want me to.’

‘No one better. Have you told Abigail?’

‘Yes, she was fine about it. She’s had enough operations to know the drill. She did say she wanted to talk to you though.’

‘I rang earlier, but she was asleep. I’ll talk to her in the morning,’ Ben had replied, pausing. ‘Is it complicated?’

‘No,’ Dr North had replied calmly. ‘And I mean no. I realise Abigail’s your partner, but I’m not lying to you. It’s a simple operation—’

‘So how soon can you do it?’

‘Tomorrow afternoon. She should stay in for a couple of days—’

‘Keep her in longer, will you?’ Ben had asked. ‘I’m not in the country and she needs looking after.’

It would be ideal knowing Abigail was safe in hospital. Dr North would undertake the operation and she would be looked after as she convalesced.

‘Abigail needs to stay in for a week, in case there are any complications. Her skin’s fragile after all the previous operations, so her recovery needs to be watched carefully.’ He had paused, no longer the doctor, now the lover. ‘Take care of her, will you? She matters a great deal to me.’

Remembering the conversation, Ben sat down behind Leon’s desk, fingering a millefiori paperweight. On one side there was a small chip from where his brother had thrown it in a fit of anger many years ago. It had been Christmas and Leon had been slighted by a colleague who had questioned his work, intimating plagiarism. Always an original thinker, Leon had reacted badly and had hardly spoken for the remainder of the holiday. It had been Detita who had finally drawn him out. And within half an hour Ben had heard them laughing in the kitchen and felt the sharp anguish of the sudden outsider.

Dismissing the memory, Ben opened his case and took out all of his brother’s notes, finally preparing to read Leon’s theory on the Black Paintings. Noticing the fading light, he pulled the desk light closer to illuminate the notebook.

To Whom it May Concern

This is my full and studied theory of Francisco Goya’s Black Paintings. I told no one that I had finally completed the solution, possibly in a mistaken attempt to protect myself and my brother. The finding of Goya’s skull has caused much grief and confusion. Anxious to avoid further problems I did not want it to become known that I had solved the Black Paintings. Whether my secrecy was necessary or just an absurd overreaction, only time will tell.

Here follows what I believe to be the meaning of The Black Paintings.

Pausing, Ben stared at his brother’s words. So Leon had finished his theory, and had lived long enough to set it down. Slowly, he turned over the first page and began to read the solution to pictures which had haunted generations.

Goya, being a liberal, was hated by Ferdinand VII and when the King regained the throne he was terrified. It was common knowledge that in the past the Inquisition had investigated his affairs. His lover, the Duchess of Alba, had been poisoned. And now here he was, deaf and old, at the mercy of a vengeful king.

Looking at the painting of The Dog I believe that Goya was making a metaphor for Ferdinand – the Dog of Spain.

Leaning back, Ben stared at the accompanying paintings, matching Leon’s notes against the relevant work.

I believe that Goya – always a liberal, always an ally of the liberals – became directly involved with the liberals who made up a substitute government in Spain, in 1822. Unfortunately, their attempt failed in 1823, and the reinstated King was brought back to Madrid. Back on the throne, his power absolute, Ferdinand VII went after his perceived enemies in order to exact a terrible revenge.

At the time Gentz wrote:

‘The King himself enters the houses of his first ministers, arrests them, and hands them over to their cruel enemies … the king has so debased himself that he has become no more than the leading police agent and jailer of his country.’

The painting which hung next to The Dog is entitled Asmodeus. The title was not chosen by Goya, so – if it is not viewed as some mystical allegory – the image becomes more immediate, its message lucid.

This picture has puzzled art historians for many years. But perhaps its meaning is not as profound as previously believed? It depicts men floating on air, at the mercy of the elements. Unable to reach the safety of the high mountain, or the firm ground beneath them, they are buffeted by fate, dreading the future ahead of them and looking back fearfully at their past. This scene depicts the fate of Everyman. And also Spain, uncertain, cut off from her roots.

As we read the paintings, we next come to The Holy Office …

Ben turned to the reproduction, then back to Leon’s notes.

In among the crowd of hags and the feared and vicious clergy is a man dressed in courtly robes. Elegant and groomed, he stands out from the procession of grotesques, his head bent towards the swollen form beside him. The gold of his chain is luminous, drawing the viewer towards him. He seems to be an Inquisitor, and I believe this man was sent from the court to deal with Goya on the instructions of a King who believed himself betrayed

… He is carrying a glass of water, which signifies life, and beside him is a monk. Monks and nuns were the very people Ferdinand VII hired to spy on his captives and report back to him. They were his own black army of quislings.

Underneath, Leon had jotted down some short, scribbled notes, almost as though he was thinking too quickly to put them into proper sentences.

(Goya was watched while he was at the Quinta del Sordo. Was Detita right? What of the mountain in the backgrounds of the paintings? The same shape, over and over again. The shape of some terrifying, ever-present threat? Or the place of safety, always out of reach?)

Ben read the passage again, then turned the page. This time Leon had organised his thoughts into a lucid continuation of his essay.

Deaf and old, Goya had exiled himself at the Quinta del Sordo. Away from court and ridicule of his infirmity, he was confronted by the silence of his own thoughts and memories. Guilt, remorse and fear colluded to force him into a malaise which would kill him unless he conquered it or escaped it. From what we know, his illness was not a recurrence of his old sickness, but on closer examination there is a pattern – a very clear intimation of the slow death of Francisco Goya.

Whistling through his teeth, Ben read on.

The Black Paintings are a ruse, a way for the artist to chart out a map of the history of Spain. And of himself. And of his life. Ultimately his death.

A creak on the floorboards made Ben tense. The threat on the phone had unsettled him, and here he was – alone in a remote house, in his dead brother’s study. He thought of the skull and cursed Francis for hiding it, for leaving him guessing. And worse, for leaving him doubting a man he had long taken for a friend.

Every memory seemed a gargoyle hunched over the past. Lack of sleep, his grief over Leon and Francis and the threat left on his answerphone were finally undermining him. His thoughts, usually incisive, were becoming mushy. He wanted to confide in someone, but didn’t dare. He wanted to get help, but couldn’t.

Dry-eyed, Ben turned back to his brother’s notes.

… the next painting, entitled The Ministration, depicts a man masturbating,

something which would have been distasteful and certainly not commissioned by a patron. But we look at the act with judging eyes, without considering another viewpoint – that the man is not relieving himself, but is caught forever without relief. Sexually impotent, like Goya, not just from age, but from disease.